On Egan’s Conception of Computation

Oron Shagrir

In Deflating Mental Representation, Frances Egan advances an exemplary account that combines realism about the computational vehicles of mental representations with anti-realism regarding their content. While the more contentious thesis concerns content, my focus is on Egan’s conception of computation, which has shaped much of the ongoing debate on physical computation in recent decades. I argue that computation and content might be more interlinked than Egan presents.

According to Egan, computational theories are formal in two ways. First, the theory specifies the mathematical function that the cognitive system computes (e.g., mathematical integration) when attaining the target cognitive capacity (e.g., navigation). In doing this, computational theory picks out two features of the computing system. One is the vehicle, which results from grouping physical states into a more abstract causal structure (Egan calls this grouping the realization function). Typical vehicles are the discrete symbols found in digital computers, but Egan sensibly allows vehicles found in neural networks and other computing systems. The other feature is the mathematical content carried by these vehicles. There is a mapping between the vehicle’s inputs and outputs and certain mathematical values (Egan calls this mapping the interpretation function). Under this mapping, these inputs and outputs can be interpreted as representing mathematical values (or mathematical contents), and the cognitive system can be understood as computing the input-output mathematical function.

The second sense in which computational theories are formal is that they are non-semantic. They never take into account the specific (e.g., cognitive or mental) content of computational states, in contrast to the mathematical content that is part of the computational theory. Egan notes—and argues in more detail elsewhere—that a large variety of computational theories in cognitive and brain sciences do not refer to specific content. This non-semantic claim is imperative for Egan’s overall theory of mental representation. If computation is somehow identified by cognitive/mental content and if cognitive/mental content is a gloss, then computation itself is, at least partly, a gloss. This contradicts Egan’s view that computational structures are “as real as written texts, maps and so on” (p. 9).

I agree with Egan that computational theories are formal in that they refer to vehicles and mathematical content, and not to specific content. Nonetheless, I have argued that specific content does affect computation and computational identity—specifically, that it determines what mathematical function the system computes (Shagrir 2020; 2022). My more modest claim here is that Egan has not addressed the worry that, on her account, computation is non-semantic.

The best way to see this worry is through a phenomenon known as computational indeterminacy (Copeland and Shagrir, forthcoming). Indeterminacy appears at two levels. First, at the level of mathematical content, stemming from the fact that there are different interpretation functions from the same vehicle to different mathematical content, each giving rise to different mathematical content. Second, at the level of vehicles, stemming from the fact that there are different realization functions—different groupings from the same physical structure—each giving rise to different computational vehicles.

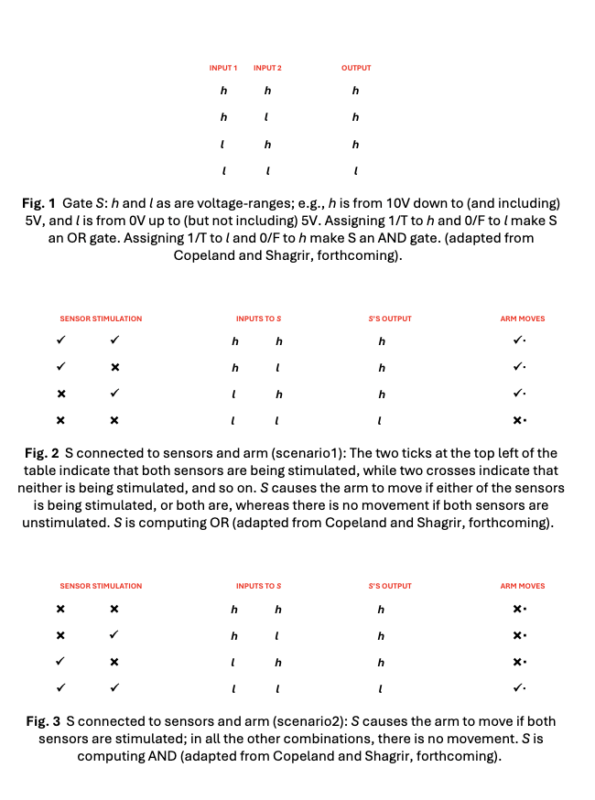

A simple example of indeterminacy at the level of mathematical content involves switching the truth-values of the inputs and outputs of a physical S-gate, potentially making it both an OR-gate and an AND-gate (fig. 1) (Block 1995; Sprevak 2010); the truth-values T/1 and F/0 are the mathematical (or logico-mathematical) content, as opposed to the specific, e.g., propositional, content. We can further connect S to sensors and arm movement in different ways. Without delving into details, it makes sense that in the first scenario (fig. 2), we would explain the arm movement by the OR function, whereas in the second scenario (fig. 3), we would explain the arm movement by the AND function.

What explains this difference? What determines the computational identity—the logical function that the system computes—in each case? Responding to Facchin (2024), Egan discusses and dismisses cases of deviant realizations and interpretations as non-explanatory, saying that the role of mathematical content “is to characterize the causal organization underlying the system’s exercise of the cognitive capacity to be explained” (p. 58). But the indeterminacy cases are more intriguing because the OR interpretation (but not the AND one) explains the movement capacity in the first scenario, whereas the AND interpretation (but not the OR one) of the very same causal organization (gate S) explains the movement capacity in the second scenario.

Some deny that the interpretation function is part of computational theories (Coelho Mollo 2018; Dewhurst 2018; Piccinini 2020; Anderson and Piccinini 2024; Klein forthcoming). This view, however, undermines Egan’s function-theoretic approach (and it also does not resolve the indeterminacy of the realization function). If computational theories do not distinguish between the OR and AND explanations, then mathematical content cannot be part of the theory proper and is just a gloss as the more specific content.

What facts make the OR function explanatory successful in one case but the AND function explanatory in the other? Assuming that some of these determining facts lie outside S—since it is the same physical gate in both scenarios—we can assume that external facts make the difference. What are these external facts? The semantic account provides a straightforward answer: roughly, specific content (carried by the voltages) determines the correct realization and interpretation functions. In our example, assume that S’s inputs represent pressure contact, or absence of contact, on the arm’s grasping surface. In the first scenario, input1’s h-values represent pressure on the surface’s left side, and input2’s h-values represent pressure on the surface’s right side (the low-values signify their absence). The output’s h-values represent pressure either on the left side or right side (or both). These representational contents would account for interpreting S as computing OR. In the second scenario, the l-values represent pressure on the surface’s left side (input1) and right side (input2), and the output’s l-values represent pressure both on the left side and right side. These representational contents would account for interpreting S as computing AND.

There are other answers to the indeterminacy cases. Some provide teleomechanistic answers that highlight the different causal relations with proximal inputs and outputs (Piccinini 2015). But since we can extend the indeterminacy to the entire system, other teleomechanists appeal to environmental facts (Fresco, Artiga and Wolf 2025). Yet others appeal to explanatory perspective but end up with positions that are apparently not realist enough for Egan (Schweizer 2019; Curtis-Trudel 2022). Egan is yet to provide her view about these indeterminacy cases, and to convince that her deflationary theory of mental representation does not lose its realist computational footing.

References:

Anderson, N.G., Piccinini, G. 2024, The Physical Signature of Computation: A Robust Mapping Account, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Block, N. 1995, ‘The Mind as the Software of the Brain’, p. 388. In Smith, E.E., Osherson, D.N. (eds), An Invitation to Cognitive Science, 2nd edit., vol. 3, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Coelho Mollo, D. 2018, ‘Functional Individuation, Mechanistic Implementation: The Proper Way of Seeing the Mechanistic View of Concrete Computation’, Synthese, 195: 3477–3497.

Copeland B.J., Shagrir, O. The Indeterminacy of Computation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming.

Curtis-Trudel, A. 2022, ‘The Determinacy of Computation’, Synthese, 200, 43–70.

Dewhurst, J. 2018, ‘Individuation Without Representation’, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 69: 103–116.

Egan, F. 2025, Deflating Mental Representation, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Facchin, M. 2024, ‘Troubles with Mathematical Contents’, Philosophical Psychology, 37: 2110-2133.

Fresco, N., Artiga, M., Wolf, M.J. 2025, ‘Teleofunction in the Service of Computational Individuation’, Philosophy of Science, 1: 19–39.

Klein, C., ‘Computational Individuation: Isomorphism, Not Indeterminacy’, Analysis, forthcoming

Piccinini, G. 2015, Physical Computation: A Mechanistic Account, New York: Oxford University Press.

Piccinini, G. 2020, Neurocognitive Mechanisms: Explaining Biological Cognition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schweizer, P. 2019, ‘Computation in Physical Systems: A Normative Mapping Account’, in On the Cognitive, Ethical, and Scientific Dimensions of Artificial Intelligence: Themes from IACAP 2016, edited by Berkich, D. and d’Alfonso, M.V., Berlin: Springer.

Shagrir, O. 2020, ‘In Defense of the Semantic View of Computation’, Synthese, 197: 4083–4108.

Shagrir, O. 2022, The Nature of Physical Computation, New York: Oxford University Press.

Sprevak, M. 2010, ‘Computation, Individuation, and the Received View on Representation’, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 41: 260–270.