Authors love when their books are being read. They love it even more when their books are being discussed. I’ve happily been in this position where the commentators have taken their time and effort to read my book and share their ideas. I am very grateful to Marcin Milkowski, Mariela Aguilera, and Alfredo Vernazzani for their insightful comments and suggestions. I owe you all a debt of gratitude!

Marcin Milkowski raises two points. First, he rightly underlies the similarities between the measurement-theoretic approach and structural representations framework. It is an important point since the necessary condition of every measurement is the structural correspondence between the measurement’s outcome and the measured object. That is why I hold that the measurement-theoretic framework is an extension of the structural-resemblance approach.

And yet, although the structural representations framework seems sufficient to explain some mental representations properties, I doubt whether it is sufficient to meet the epistemological, semantical, and metaphysical challenges for the theory of imagistic thoughts. The latter is not reducible to the theory of mental representations.

Second, and more importantly, Marcin Milkowski and Mariela Aguilera ask whether the measurement-theoretic approach to imagistic thinking can be extended and unify the explanation of all kinds of thoughts. I find this question very intriguing and hard. On the one hand, I explicitly reject the belief that images can be foundational for propositional representations. Such an approach does not seem convincing. My thought that three is the square root of nine does not involve any images and does not seem to require any of them. That is why I describe imagistic and propositional thoughts as playing different roles in the thinking machinery.

However, I deeply believe that the measurement-theoretic framework can be extended to give a unified account of thinking. Although it is not the book’s topic, the possibility of such an extension seems very promising. For one thing, there are fruitful attempts to apply the measurement-theoretic framework to the analysis of propositional attitudes (Dresner, 2006; Matthews, 2007). For another, there is a close and natural connection between the measurement-theoretic approach and computational framework (Matthews and Dresner, 2017). Yet, we need a well-conceived division of labor between imagistic and propositional representations within the measurement-theoretic framework. How can such a division look? I do not have an answer, but if I were looking for such, I would probably reread Kant. For him, concepts were measures (rules) taken to identify the world’s states in propositions. Images (schemata) were representations of these measures. For instance, the concept of 5 is a measure of the number of elements in the set. It can be applied in propositions such as ‘there are five apples’. An image of five apples is a representation of such a measure. It is a diagram of the number 5. And while I am not saying it is a correct answer, I hold that it offers a possibility to think about such an answer.

In her insightful comment, Mariela Aguilera doubts whether we should reject the traditional and well-grounded division between attributive and singular content. Some passages in my book may suggest that I make such a move. For instance, I hold that images do not describe their objects but identify them. Moreover, I defend the view that iconic content cannot bear predicative functions. Predicates require logical form iconic content lacks.

However, I do hold that cognitive systems can use iconic content to describe or attribute properties to some objects. For instance, perceptual systems can use iconic content to identify objects by attributing them properties (Burge, 2010). Language-based systems can use images to describe depicted objects. Yet, I hold that the iconic properties being attributed by the system are measurement predicates. Let me explain it.

The idea of measurement predicate is taken from the measurement theory. If I hold that the air temperature is 20°C, I do not hold that the temperature is in some dyadic relation to the number 20. The number 20 does not predicate of this temperature that it has the property of being even or being twice as much as the temperature 10°C. The number 20 is a measurement predicate that represents the way we identify a physical magnitude by finding its place on a scale.

Let us take an image of John representing him as bald. According to the measurement-theoretic framework, an image of John being bald represents the way of identifying John. The property of John being bald is the measurement predicate used to identify John. It does not predicate anything of John, as if there were some relation between these properties and their object seen in the picture, i.e., something we predicate of and a predication. A portrait of John localizes John by determining the properties that serve to recognize him. For instance, it represents the property of being bald, a measurement predicate used to identify John.

However, once you recognize John in the picture, you can predicate of John that he is bald. For instance, some language-based systems can use a picture to describe John. In the same way, the indication of the thermometer, such as 20°C, does not predicate the property of being even of the air. It identifies this temperature on a scale. However, once this value is found, we can predicate it of the air, e.g., ‘it is 20°C outside’.

In the last comment, Alfredo Vernazzani analyses the problem of canonical decomposition. According to the well-known Fodor’s argument, images lack canonical decomposition since they can be divided arbitrarily into representational parts. Vernazzani holds that this argument is invalid since we can distinguish representational primitives based on our perceptual capacities (see also Burge, 2018). The property of being a picture part piggybacks on our perceptual capacity to recognize what it is a part of.

There are certain prospects for Vernazzaini’s approach. Foremost, it puts some psychological constraints on our theories of iconic content. Moreover, as Vernazzani rightly suggests, it can strengthen the view I advocate in the book.

However, I am not convinced that the psychological approach is of enough modal strength to solve the problem of canonical decomposition. It is a metaphysically contingent fact what kind of perceptual capacities we possess. Let us assume that all people went color blind one day. It does not necessarily follow that paintings’ colors stopped being their representational parts. Next, let us assume that one day people will form the capacity to see different shades of black. It does not imply that a black-and-white triangle diagram will start to have more representational parts.

Does it mean that the psychological interpretation is wrong? No, it does not! It suggests, however, that some other constraints should supplement it.

To end up with some closing remarks, I hope Thinking in Images provokes thinking and gives new topics to the discussion (not necessarily in images). That is the only thing a philosopher can wish for.

Literature:

Burge, T. (2010). The Origins of Objectivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burge, T. (2018). Iconic Representation: Maps, Pictures, and Perception. In S. Wuppuluri, F. A. Doria (Eds.), The Map and the Territory. Exploring the Foundations of Science, Thought and Reality (pp. 79-100). Springer.

Dresner, E. (2006). A Measurement Theoretic Account of Propositions. Synthese, 153, 1-22.

Matthews, R. J. (2007). The Measure of Mind. Propositional Attitudes and their Attribution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Matthews, R. J., Dresner, E. (2017). Measurement and Computational Skepticism. Noûs, 51 (4), 832-854.

What I find most interesting about this discussion is that it expresses a common desire, if somewhat inchoate and confused, for a unified theory of representation and thought, that covers images, language, symbolic systems such as maths and logic, and all other forms of representation.

One of the things that is happening here and elsewhere in various sciences, is an urge to give more importance to images in our thought, while at the same time trying to hold on to symbolic structures as important and different.. In theoretical linguistics for example some linguists believe in the importance of images underlying language, but still want to hang on to grammar as somehow representing some fundamental and separate structure of the mind.

All of this is happening in the context of the greatest cultural earthquake in history, in which our unimedium book of the world and textual civlisation have been de facto replaced by our multimedia screen of the world and the multimedia civilization of the internet . A screen which is based like our own mind on the most quantitatively important form of information on the net, namely video (like our mind is based on video/consciousness).

If we’re looking for a unified theory of representation, AI provides the foundation (and surprising that no one has referred to this which should be de rigueur in any such discussions). – scenic analysis

Let’s put that in a more embracing proposition – “All thought, and all forms of representation, including vision, visual and other images, AND symbolic systems are based on scenic composition (and analysis/ decomposition).” Note of course that I am extending AI’s scenic analysis far beyond its intended sphere of purely visual images.

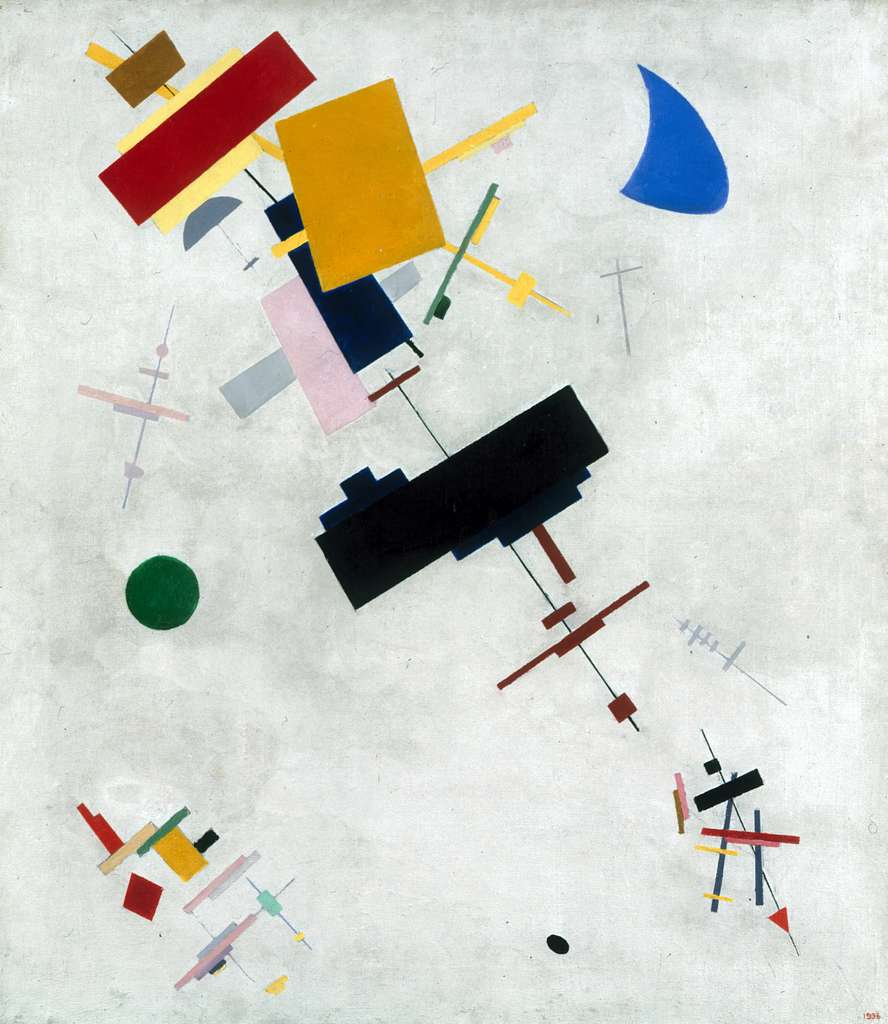

What is scenic composition/analysis? What happens when we look at an image – the scene in front of us, a photograph, a painting?#

Not a lot according to Pior and possibly millions of others. He has a particular measurement theoretic theory about images but: ” I explicitly reject the belief that images can be foundational for propositional representations. Such an approach does not seem convincing. My thought that three is the square root of nine does not involve any images and does not seem to require any of them.”

AI scenic analysis argues that a great deal of propositional reasoning is going on in analysing images – that we analyse them in terms of bodies (objects); including

Who does What to What Where Why Whence and Whither.

Who or Which Body is doing What Action to Which Other Bodies in Which Field of the world at What Time (in the space-time continuum) and what happened before to occasion this scene, and what will happen in the future – where are they all going with this interaction?

(and how does all this relate to My Body ( Me – the Viewer of this scene?”)

A vast amount of propositional analysis for example is required to understand:

https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.mutualart.com%2FArtwork%2FHercules-fights-Thanatos-to-free-Alcesti%2F7B41F9BE431FF926&psig=AOvVaw3_SeUIFDZ8I6qAU61bZLTa&ust=1681762273700000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=2ahUKEwiGlNHomq_-AhVMbDABHfe7DwAQjRx6BAgAEAw

and indeed the vast majority of paintings and photographs.

In fact, neuroscientists tell us that vision-scenic analysis takes up something like 30-40% of brain resources – which would be passing strange if a staggering amount of reasoning were not going on

(Note BTW that scenic composition – basically composing and moving the bodies of the world -is the basis both of analysis of images, and construction of images. It is what the painter and the photographer do and also, actually the writer as well as the audience..

Let’s simplify our definition of Scenic Analysis – it can be shortened to

Body-Action-Body (Field-Time)

And scenic analysis is the basis of life and movement through the world – we are continuously analysing Body-Action-Body – our whole life depends on it.

But what’s that to do with language? Well Noun-Verb Noun – Body-Action-Body.=- the basic scenic structure of language.

And what on earth to do with maths? 3 + 3 for example?

Well that’s a scene. Someome taking multiple (3) bodies and physically putting them next to multiple more bodies. Maths makes no sense if it is not based on the real world composition of bodies.Sentences — equations – propositions are all scenes. Symbols are just the subtitles on the scenic images. When you realise that, you realise the whole rationale for symbolic thought – which is that it represents a massive short-cut/replacement for imagistic thought (and not something separate at all. It’s much computationally easier to think in terms of simple uniform symbols or name-tags for bodies than it is to think in terms of the extremely complex forms of actual real world bodies. Of course there’s a big price to be paid for that on the other hand – “blind logic” .We become subject to the illusion that symbolic thought is all we are doing and is possible WITHOUT underlying scenic thought. Which is similar to the illusion that if s.o. says “Catch” and I catch the ball, my brain is not doing any unconscious imaging.

Obviously I could go on.. but I’ll stop now. If you want to throw challenges at me – any representations that cannot and do not have to be analysed in terms of composing bodies – “the quality of mercy” somesuch – anything – have a go.

It is easy to establish that ‘Ideas’ underlie all digitisable thoughts like words and images. Ideas are fundamental and can be directly communicated between subjects. I would suggest that ‘ideas’ is the correct term rather than the ‘imagistic thoughts’ used by the author, since those can, in principle, be digitised, while ‘ideas’ (‘Forms’ in Plato) cannot be.

V interesting and raises v important point.

It’s a common thought – “language/maths/logic is the communication of ideas”.

{NB you say it’s easy to establish ideas are universal .. but give no example. Try it – you’ll find it’s v difficult.]

What is an “idea?” I’d say “a combination of concepts”. “Roses” and “red” are concepts. “Roses are red” is an idea.

So what you are actually talking about is our conceptual system – the system that underlies the words of language and also many kinds of graphics like the “man” “woman” graphics on toilet doors.

No, concepts/ideas are absolutely not fundamental to cognition, thought, representation. Central but not fundamental.

The idea that follows here is that cognition/thought etc. are structured by a multilevel tree of knowledge/images/thoughts/bodies.

I would say that tree operates continually in our minds, structures all thought although only one level may be conscious at a time.

The tree has multiple “levels of realism”.

These include the main 3 levels of generality/individuality – General/Classical/Individual. – i.e. everything/every body we see is classified/identified simultaneously on all 3 levels. eg as “A Body”/ “A cat”/ “My Felix the cat”

Only Real Images – e.g. photographs, cinematographics-movies and normal vision – are fundamental and can picture Individual Reality. – that is to say Single Individual Bodies taking streams of single individual actions in single fields at single points in Real Space-Time (incl. my Felix)

eg. https://s.hdnux.com/photos/75/76/57/16247750/5/rawImage.jpg

The real images of vision/consciousness are the fundamental foundation of our cognition because they are the ONLY way to record the forms of real individual bodies in real space-time.. Evolution is not stupid. It puts the real images of Vision/Consciousness at the basis of everything cognitive because it wants to ensure that humans Get and Stay Real.

And ultimately Real Individual Bodies in Real Space-Time are the only reality there is.

Our conceptual system exists to CLASSIFY and AMASS single bodies etc. – to compare these single bodies with others like them and to place their single actions within the boxes of larger multiactions You can have concepts and ideas about the individual reality shown in Real Images. E.g “A man is shooting Oswald”.about that photo – ideas which classify but do not directly depict.

Concepts and ideas cannot begin to substitute for real images and real indivdiual bodies. They are a complementary higher level of cognition and Reality. And they are both more general and vaguer and as such are always to some extent fictions/”lies”. Essential tools of cognition but not as reliable as Real Images of the Real Things/Bodies. Only Oswald photos/movies can show what actually went on. A textual description of that event – a set of descriptive ideas – is extremely vague and shadowy by comparison.

This of course upends 2000 years of textual civilisation which says a la Plato that images are to some extent lies and only the Classical Ideas of Language and Logic are Really True. And has yielded endless philsophical pearls of truth such as “Snow is White”.

Well no like all ideas that’s a partial falsehood. Look at Real Images and you’ll find snow can be sooty, bluish, sandy, shades of grey and much else depending on which Individual Bodies of Snow in the real world that you are looking at. Ultimately this is the basic philosophy of science, although arguably scientists don’t know it is. The philosophy which says that all ideas – scientific theories and generalisations – about the world have to be supported by evidence – i.e Real Images of Real Single Individual Bodies acting as science’s general/classical ideas about the Orders and Classes of Bodies in the real world, claim.

PS Compare the ideas (& verbal propositions) of texts with the Real Images – photos/movies of Oswald:

“here are three verbal descriptions of the shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald from newspaper articles:

“A man lunged forward and fired a shot into Oswald’s stomach from a foot away, causing him to gasp and crumple to the ground.” (New York Times, November 25, 1963)

“As Oswald emerged, a heavy-set man in a hat lunged at him with a gun and fired, hitting him in the abdomen. Oswald cried out and fell to the pavement.” (Dallas Morning News, November 25, 1963)

“A stocky man wearing a dark hat and overcoat suddenly lunged toward the suspect and fired a shot at point-blank range, hitting him in the lower abdomen.” (Washington Post, November 25, 1963)

https://s.hdnux.com/photos/75/76/57/16247750/5/rawImage.jpg