In The Multiple Realization Book we articulate an account of multiple realization that is based on the idea that the “job description” for multiple realization is to be incompatible with brain-based theories of the mind and therefore to strongly favor functionalist and other realization-based theories. Multiple realization is supposed to block reduction (especially type-identification) and pave the way for functionalist or realization theories, and thereby to justify the autonomy of the special sciences, especially but not only the autonomy of psychology. This is the view defended by Hilary Putnam (1972), Jerry Fodor (1974), and Philip Kitcher (1984). And it is the “received view” in philosophy of mind/psychology and philosophy of science generally. It is widely assumed by contemporary philosophers of mind, science, and metaphysics. In short: We have special sciences because the world requires them; and the world requires them because the phenomena that they explain are multiply realizable.

The success of multiple realization at doing its job has not gone unquestioned. But the critiques have not persuaded true believers in multiple realization. Writing in 1997 about his own influential argument (advanced in 1974), Jerry Fodor says, “The conventional wisdom in philosophy of mind is that ‘the conventional wisdom in philosophy of mind [is] that psychological states are “multiply realized”…[and that this] fact refutes psychophysical reductionism once and for all.…’ Despite the consensus, however, I am strongly inclined to think that psychological states are multiply realized and that this fact refutes psychophysical reductionism once and for all. As e.e. cummings says somewhere: ‘nobody looses [sic] all of the time.’” (Fodor 1997: 149, embedded quote from Kim 1992: 1).

But if we’re right the evidence for multiple realizability—especially but not only of psycho-neural multiple realizability—is much weaker than philosophers like Fodor (and following Fodor) have assumed. On our view the fact of widespread multiple realizability cannot justify the autonomy of the special sciences because there is no such fact. The “conventional wisdom” on why there are special sciences is not correct.

As we’ve said, we think that actual cases of naturally occurring multiple realizability are relatively uncommon. But note that even if multiple realizability was common in certain domains, e.g., economics, that would not be sufficient to do the job of justifying the autonomy of psychology or of the special sciences in general. Contrariwise, even if there turned out to be a distinctive reason for thinking the psychological processes are multiply realizable, after all—maybe they really are abstract computational processes that could be implemented in “copper, soul, or cheese” as Putnam claims—this too would not justify the autonomy of the special sciences in general. Thus, even if we are wrong about psychological processes and they really are abstract computational processes, that will have no bearing on the status of meteorological, geological, and chemical processes which are pretty clearly not abstract computational processes. So even in that case we will still need a better general answer to the question of why we have the special sciences, or else admit that there is no one general answer.

The competing view that we propose is that a plurality of sciences is justified so long as they each provide causal explanations, where causal explanation is understood in terms of difference-making, e.g., in terms of interventionist causal explanation à la Woodward’s Making Things Happen (OUP, 2003).

This is a sufficient condition for recognizing a plurality of sciences in our view. But we admit that it might not be necessary or perfectly general. There may be sciences that do not traffic in causal explanations, dependence explanations, or even in non-causal difference-making explanations. So although we think we can make some progress on understanding why we have some kinds of special sciences, we may not yet have a general answer to the question, “Why is there anything but physics?” Nevertheless we think our approach is more promising than the “conventional wisdom” and yields a better account of the autonomy of the many sciences from one another than does the standard picture, based as it in on the phenomenon of multiple realizability.

Coda

The question “Why is there anything but physics?” is ambiguous between a question about ontology and about epistemology, and the conventional Fodorian wisdom connects the two: There is a plurality of distinct and autonomous forms of inquiry (sciences) because the world contains a plurality of ontologically distinct and irreducible kinds of things. Our approach is less demanding in that we do not require explanations to be irreducible to be justified, and therefore allow that there could be more kinds of explanation than kinds of things, i.e., explanatory pluralism.

There is an important question that is not satisfactorily answered by either the conventional wisdom or our own view. In the preface of The Multiple Realization Book we quote Wilfrid Sellars famous remark that the aim of philosophy is “to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term” (1963: 1). Given our naturalism, the legitimacy of philosophy as a form of inquiry ought to be justified in the same way as any other form of inquiry. But it seems wrong to say that explanation in philosophy is justified only to the extent that multiple realization guarantees the existence of distinct and irreducible philosophical entities to be objects of philosophical inquiry. And it doesn’t strike us as plausible that philosophical explanations pick out causal difference-makers. It is somewhat more plausible that philosophical inquiry aims to discover dependence relations and their difference makers. But we are not convinced that we yet have an account that adequately explains how there can be philosophical knowledge and explanation, that is, how philosophy itself can be a form of inquiry.

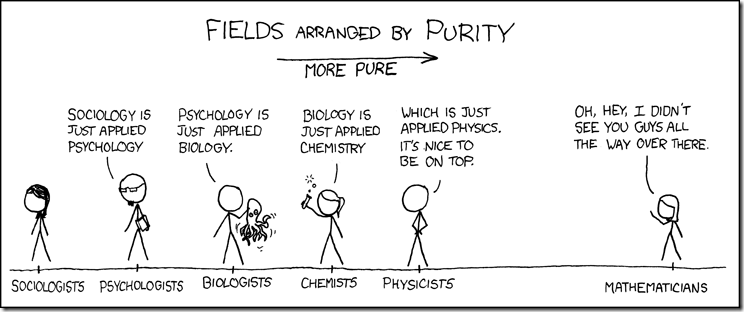

Header image credit: xkcd