In Knowledge and Practical Interests, Jason Stanley (2005) provides a number of examples to show that propositional knowledge is not gradable. Consider the following two sentences:

(a1) Sean knows that Obama is President better than Meredith does.

(a2) Alyssa knows that Obama is President better than Philip knows that Clinton is a Democrat.

Stanley (2005) argues that such sentences are unacceptable in the English language, and he surveyed non-philosophers who also judged the sentences to be unacceptable.

While I agree that such sentences do not seem natural, I disagree that they provide evidence against the gradability of propositional knowledge. In support of this, I introduce a distinction between two types of propositions:

- Low-cost propositions.

- High-cost propositions.

I refer to propositions as either “low-cost” or “high-cost” in much the same way as various pieces of art might be referred to as “valuable” or “worthless”. In other words, the property of being low-cost and the property of being high-cost are context-dependent properties; they are not intrinsic properties of the proposition. Moreover, there are of course many gradations between these two extremes of low-cost and high-cost propositions.

To further illustrate the distinction, suppose that Charles knows that the office meeting starts at 12:00PM. Here, the relevant proposition (“the office meeting starts at 12:00PM”) is a low-cost proposition, since presumably, Charles’ reception of the proposition is largely passive, requiring little cognitive effort or cost. By contrast, suppose that Jenna knows that every integer greater than 1 is the product of primes. Here, the relevant proposition (“every integer greater than 1 is the product of primes”) is a high-cost proposition, since Jenna’s reception of the proposition likely involves significant cognitive engagement, requiring a fair amount of mental cost and effort.

To explore how this idea might pertain to degrees of knowledge, I ran a short survey to see how the low-cost versus high-cost distinction affects people’s judgments about graded propositional knowledge ascriptions. I presented each subject with the two statements adapted from Stanley (2005), (a1) and (a2), which contain low-cost propositions, and I also presented each subject with three additional statements containing high-cost propositions, namely:

(b1) Tim knows that the speed of light is a physical constant better than Steven does.

(b2) Mark knows better than Paul that every integer greater than 1 is the product of prime numbers.

(b3) Josh knows that mass is a measure of energy better than Jordan knows that the speed of light is a physical constant.

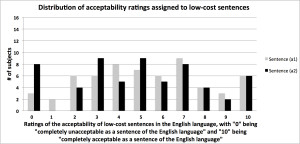

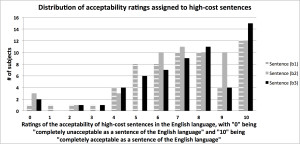

For each sentence, subjects were instructed: “On a scale of 0-10, rate each sentence according to how acceptable it is as a sentence of the English language.” “0” was labeled as “completely unacceptable as a sentence of the English language”, and “10” was labeled as “completely acceptable as a sentence of the English language”. The survey was given to 60 subjects. 20 subjects received the sentences ordered with the high-cost sentences preceding the low-cost sentences: (b1), (b2), (b3), (a1), (a2). Another 20 received the sentences ordered with the low-cost sentences preceding the high-cost sentences: (a1), (a2), (b1), (b2), (b3). And yet another 20 received the sentences ordered with the low-cost sentences interpolated between the high-cost sentences: (b1), (a1), (b2), (a2), (b3). There was no evidence of order effects on judgments for any of the five sentences.

Merging the data from the three groups, in paired t-tests, the following findings emerge:

I. The average acceptability rating of every high-cost sentence was significantly greater than the average acceptability rating of every low-cost sentence:

1. (b1)(mean 6.93) > (a1)(mean 5.28), p < 0.0001

2. (b2)(mean 7.35) > (a1)(mean 5.28), p < 0.0001

3. (b3)(mean 7.17) > (a1)(mean 5.28), p < 0.0001

4. (b1)(mean 6.93) > (a2)(mean 4.93), p < 0.0001

5. (b2)(mean 7.35) > (a2)(mean 4.93), p < 0.0001

6. (b3)(mean 7.17) > (a2)(mean 4.93), p < 0.0001

II. No high-cost sentence had an average acceptability rating that was significantly greater or less than the average acceptability rating of any other high-cost sentence:

7. (b1)(mean 6.93) < (b2)(mean 7.35), p = 0.2798

8. (b1)(mean 6.93) < (b3)(mean 7.17), p = 0.5247

9. (b2)(mean 7.35) > (b3)(mean 7.17), p = 0.5723

III. No low-cost sentence had an average acceptability rating that was significantly greater or less than the average acceptability rating of any other low-cost sentence:

10. (a1)(mean 5.28) > (a2)(mean 4.93), p = 0.3806

Thus, in accordance with the high-cost versus low-cost distinction, subjects were significantly more willing to say that statements (b1) – (b3) are acceptable in the English language than they were to say that statements (a1) – (a2) are acceptable in the English language.

This seems to gives some credence to the idea that graded propositional knowledge ascriptions are more likely to sound awkward if they contain only low-cost propositions. One potential explanation of this can be seen by looking at another value-related graded verb: “draws”. Consider the following statements:

(c1) Joan draws various squiggles that come to mind better than Nathan does.

(c2) Michael draws various squiggles that come to mind better than Erica draws various zigzags that come to mind.

(c3) Sarah draws landscapes better than Kate does.

(c4) Krista draws landscapes better than Amber draws portraits.

Statements (c1) and (c2) sound significantly more awkward than (c3) and (c4). Nevertheless, the verb “draws” clearly accepts degree modifiers. So why are the first two statements more awkward than the last two? The reason, it seems, is that it’s difficult to make comparative judgments in cases in which there is no obvious type of active, effortful skill required by the subjects. The same point might explain why examples sometimes used by epistemologists make it seem as if propositional knowledge is not graded: i.e., because they tend to use low-cost propositions that are passively received with little mental exertion or cost (in other words, propositions that more closely resemble the first two drawing statements than the last two).

[Cross-posted at Experimental Philosophy]