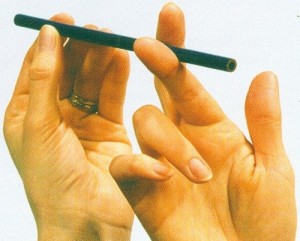

In the first section of chapter 7 of The Peripheral Mind, I discuss Aristotle’s Illusion, a tactile-proprioceptive illusion that is very easy to replicate by crossing two of your hand fingers, and touching the region thus created between the fingertips with a cylindrical object. Most people report that they feel touched by two objects. I put forward and analyze a version of this illusion in which I move a pen between the fingertips.

I lie down on my back and keep my left palm perpendicular with respect to my body, a few centimeters above it, with the thumb pointing towards the body, and with fingers 1 (index) and 2 (middle) crossed (finger 2 above finger 1). Then I touch, say, finger 2 first and then finger 1 with a pencil. To do this, I intend and move the pencil upwards, but when it makes the second touch, namely on finger 1, the movement seems as if it was not upwards but downwards. So the experience of the direction in which I move the pencil feels both upwards and downwards roughly at the same time. It is a paradoxical feeling. I go upwards, so I expect to touch the finger that is above, and yet I end up touching the finger that feels below. So it is like a tactile version of Escher’s ascending-descending staircase.

I analyze the contribution of the PNS activity in the fingertips when this puzzling experience occurs. What the original version of the illusion shows is that fingers have intrinsic felt location; each finger has an intrinsic interior and an intrinsic exterior, and they are aligned with the extrinsic (that is, physical) interiors and exteriors when the fingers are not crossed. When the fingers get crossed, there is a mismatch– the intrinsic interiors are now extrinsic exteriors, and vice versa. I am interested in the component of the total Escher type experience that is related to the phenomenology of the felt direction of motion of the active finger, and argue that the counterfactual that explains the contribution of the intrinsic locatedness of the touched fingers to this component of the experience is the following:

Had the extrinsic interiors of the fingers not been intrinsic exteriors, everything else being equal, the upward motion of the active finger would not have been felt as also downward.

However, empirical studies show that after long-term reversal (6 months of crossed fingers in Benedetti 1991), whether the fingers are crossed or not does not matter; the subjects are equally good at identifying and perceiving correctly with crossed and with uncrossed fingers (unlike in the visual case, when wearing inverting goggles generates a mere adaptation — I discuss inverting goggles in chapter 8). This means that the reason we feel intrinsic and extrinsic interiors of our fingers is a history of stimulation, which is very rich for the interiors (due to the shape of our hand and the regularities of our haptic environment), and quite poor for the exteriors (for the same reason — we rarely, if ever get touched simultaneously on the exteriors of a pair of fingers). The real cause of the Escher type motion illusion when I cross my fingers for the first time is an absence; the absence of a sufficiently long stimulation of the touch contacts. But the absence of such a history of stimulation is not the type of process that is present at the level of the contact points of the touch when I do have the illusion. The lack of stimulation is not a positive fact about the PNS when I am touched. So the positive fact about the PNS when I am touched, namely, that the nerve endings become activated, is not a causal contributor to my experience since the only one causal contributor, if we follow the counterfactual analysis, is the lack of sufficient past stimulation. Yet, it is pretty clear that the one-shot stimulation of those contacts, when I cross the fingers, is a contributor to my paradoxical experience. So we should understand these PNS processes as constitutive contributors to the experience. I make the following analogy in the book:

“To change the famous story a bit, the Count of Monte Cristo, who is trapped in his prison cell, follows the Mad Priest’s escape plan, and they start digging a tunnel through the thick stone walls of the prison fortress, having their spoons as their only usable tool. They need to dig for 10 years in order to complete the 5 meter long hole which would enable them to escape. Suppose we focus on the hole as it appears after 5 years of digging. Suppose the Mad Priest scrapes out half a spoonful of detritus from the wall. The scraping of the wall is a cause of the hole being, say 2 meters long, but, intuitively, why they are still trapped is because there has not been sufficient scraping yet. The absence of sufficient scraping is the cause of their being trapped. But what about the hole being 2 meters long? Intuitively, this is not a cause of their being trapped, but a constituent of this fact. To be trapped, in that situation, is partly constituted by the fact that the hole is not 5 meters long yet. Similarly, when the hole becomes 5 meters long, that fact will constitute their escape, although the hole becoming that long was caused by the constant scraping for 10 years. The scraping is a cause of the escape, but the length of the hole constitutes it. You can now replace the lengthy successive scraping above with the lengthy successive stimulation of the finger skin by external surfaces, and the length of the hole with the current activity of the PNS at the level of the fingers, and you get the way I think of the PNS as constitutive of the experience.”

David Papineau objected to this argument of mine (at a time when I had already submitted the final version to the publisher) that it involves some kind of causation at a temporal distance, if the PNS activity at the moment of touch is not taken as a causal but as a constitutive contributor. One answer is that ascribing an absence as a cause is in fact contrastive, so that implicit reference to a non-gappy causal process is secured: “the absence of past stimulation of the physical exteriors caused …” has as its true logical form “the presence of stimulation of the physical interiors rather than of the exteriors caused …” (See Schaffer 2005)

References

Benedetti, F. (1991): “Perceptual Learning following a Long Lasting Tactile Reversal,” Journal of Experimental Psychology 17 (1): 267-277.

Schaffer, J. (2005): “Contrastive Causation,” Philosophical Review 114 (3): 327 -358.

Hi Istvan,

Thanks for another fascinating post.

If I understand you correctly, you think that the event of the activation of the nerve endings when you are touched (call this event N) is not the cause of your (Escher type motion illusion) experience, E, because the “real” cause is the presence a certain history of stimulation “of the physical interiors rather than of the exteriors”. Call this history of stimulation H. It seems (but I may have misunderstood you) that your argument is that since H causes E, and since in the absence of H, N would not “contribute to” (or bring about) E, it follows that N does not cause E (from which you conclude that N constitutes E). Could you clarify what your reason for thinking so is? In other words, could you clarify why you think H and N cannot both be causes of E? To make the question clearer, I will utilize the familiar (and hopefully unproblematic?) notion of a structuring cause introduced by Dretske (in Explaining Behavior, chapter 2, especially pp. 48-50).

One of Dretske’s examples is a furnace controlled by a thermostat. When the temperature drops below, say, 16 Celsius (call this event A), the thermostat is activated (call this event B) and as a result the furnace ignites (call this event C). The furnace works in this way because it was built by technicians and engineers in this way. Call this building and design history D. Dretske calls A a triggering cause of the furnace’s “behavior” (the behavior is the fact that B causes C), and D a structuring cause of the furnace’s behavior. D explains why the furnace is structured in such a way that A causes B, and B causes C.

The crucial point is that the fact that D is a structuring cause of the furnace’s behavior does not prevent A from being a cause of B, and does not prevent B from being a cause of C. D does not cause B and also does not cause C. Rather, D causes the furnace to have a certain structure, such that A causes B, and B causes C.

On its face, it seems that it is possible to apply a Dretske-style analysis to your Escher type experience case. Roughly, we could say that H is a structuring cause. It causes the nervous system to have a certain structure. Because of this structure, N causes (in an ordinary sense) E. So, the claim that H is a structuring cause (i.e., it explains why N causes E), and the counterfactual claim that if H did not occur, N would not cause E, are consistent with the claim that N causes E.

So, if this Dretske-style analysis of the illusion you present is on the right track, I do not see (in your post, that is) a reason for denying that N is a cause of E. I guess, therefore, that I have made a mistake in applying the notion of a structuring cause to the Escher type illusion you discuss. Could you clarify where my mistake lies?

Hi Assaf, excellent objection, which I failed to think about in the book, and which I’m not sure I now have a knockdown answer to, but here is a try. It seems to me that Dretske’s cases involve a looser connection among the three events: structuring event, triggering event, and effect event. So consider the example “parental neglect caused the boy to behave brutally with his pets”. He is caused to cause suffering. Neither the boy’s behavior, nor its effect on animals happen in virtue of something, but merely because of something. In my case,things seem different. The intrinsic interiority/exteriority of the finger skin regions occurs or is present because of past stimulation patterns, whereas the experience has its features in virtue of the current stimulation being of regions that are intrinsically interiors or exteriors. It has its features in virtue of, rather than because of the intrinsic interiority/exteriority of the skin, to the extent that the latter are really felt interiority/exteriority, so they are a phenomenal component of the experience. In other words, the current stimulation in itself does not ensure that the experience will occur, unless the stimulated nerves are phenomenally intrinsically in some way or other (in the book I actually call them “intrinsic phenomenal interiors/exteriors). And they are caused to be one way or another by past stimulation patterns. Admittedly, this is a bit different and more sophisticated than what you will find in the book. So, yes, I think the objection based on the “structuring/triggering cause” distinction is something that I should have considered, and I don’t yet have an answer to satisfy me.