We are very grateful to John Schwenkler for inviting us to blog at Brains. Our main claim in Consciousness, Attention, and Conscious Attention is that consciousness and attention must be distinct kinds of mental states. We offer four arguments, each explicated in a separate chapter. The first argument is that a vast amount of research shows that many forms of attention, even at the personal level, occur automatically and without conscious awareness. We emphasize the variety of attentional processes to boost this claim. Second, we argue that most philosophical views on the nature of consciousness entail the dissociation between consciousness and attention. Third, we claim that there is a distinctive kind of conscious attention that is not reducible to attention or conscious awareness. And fourth, what is perhaps the strongest empirical argument we develop, we claim that considerations about evolution strongly suggest that consciousness and attention must be dissociated. What follows is a more detailed description of these arguments and the contents of the book.

We are very grateful to John Schwenkler for inviting us to blog at Brains. Our main claim in Consciousness, Attention, and Conscious Attention is that consciousness and attention must be distinct kinds of mental states. We offer four arguments, each explicated in a separate chapter. The first argument is that a vast amount of research shows that many forms of attention, even at the personal level, occur automatically and without conscious awareness. We emphasize the variety of attentional processes to boost this claim. Second, we argue that most philosophical views on the nature of consciousness entail the dissociation between consciousness and attention. Third, we claim that there is a distinctive kind of conscious attention that is not reducible to attention or conscious awareness. And fourth, what is perhaps the strongest empirical argument we develop, we claim that considerations about evolution strongly suggest that consciousness and attention must be dissociated. What follows is a more detailed description of these arguments and the contents of the book.

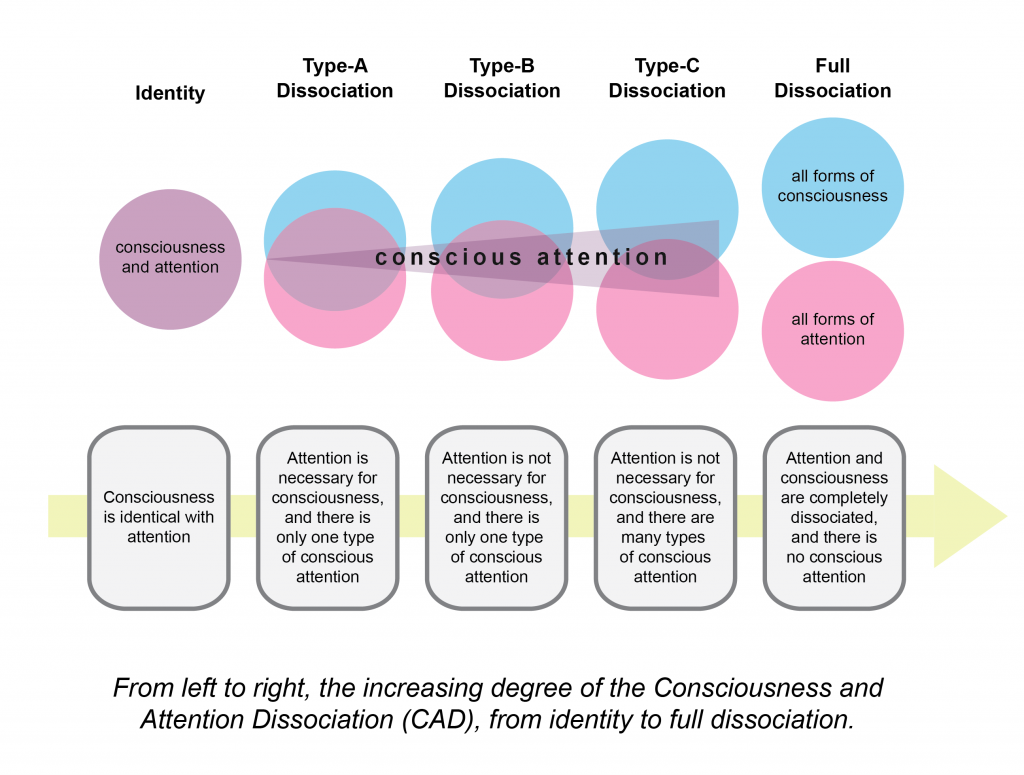

Chapter 1 introduces the main goal of the book, which is to provide a systematic account of the relationship between consciousness and attention in order to better understand the purpose of conscious awareness. By describing a spectrum of dissociation between consciousness and attention, some conceptual clarity to the debates concerning these topics can be achieved. This proposal concerning dissociation is referred to as the Consciousness and Attention Dissociation (CAD) and includes theories that range from claiming that they are identical processes to theories that argue for a complete dissociation (see illustration below). The requirements for the different levels of dissociation are outlined in this chapter, and the overlap between the two—conscious attention—is introduced.

Chapter 2 presents an overview of the research on visual attention, which has been studied extensively in cognitive psychology and neuroscience. The studies discussed are limited to the major empirical findings on visual attention that have implications for the scientific understanding of consciousness. The chapter includes studies on feature-based attention, spatial attention, object-based attention, effortless attention, the mechanisms supporting the different forms of attention (e.g., neural structures and pathways), and the evolution of these mechanisms. This review is important for the book’s primary argument that consciousness and attention must be dissociated at some level, as there are functionally different forms of attention that seem to operate independently and to have evolved at different times from each other—an argument that is difficult to make for consciousness.

Chapter 3 focuses on the philosophical theories about consciousness and how they might relate to our understanding of visual attention. By examining several theoretical considerations, a robust form of dissociation between consciousness and attention is apparent. It is argued that dissociation is not only a plausible view, but that the more severe forms of dissociation (e.g., Type-B or Type-C dissociations), seem to be entailed by the standard distinctions used in consciousness research. This approach helps disambiguate terms that need to be reconciled in order to improve exchanges between theorists, and also systematically unifies debates that have been largely isolated from one another. The account presented in this chapter reveals several affinities among the extant views that have not been properly understood. The chapter’s main conclusion is that many of the current debates show that a more comprehensive theory of the relationship between consciousness and attention is needed, and that a dissociation between the two is an essential feature of this theory.

Chapter 4 examines the theoretical possibility of having systematic forms of overlap between consciousness and attention—what has been termed ‘conscious attention.’ This is a possibility that is compatible only with views that dissociate consciousness and attention, but without denying that they can overlap in regular ways. The views that preclude such an overlap are identity theories and full dissociation theories. For identity theories, by assumption, all forms of consciousness are automatically forms of attention. At the opposite end of the spectrum, for full dissociation theories, there is no possible overlap between consciousness and attention; although they might seem to occur in tandem, such theories must claim that there are no systematic overlaps between them. In this chapter, several forms of conscious attention are described, including those related to phenomenal experiences, dreams, self-awareness, autobiographical memories, reflexive thoughts, epistemic seeing, and effortless attention. The chapter’s conclusion is that conscious attention is an important form of attention that requires further study and will ultimately help us better understand the purpose of consciousness.

Finally, chapter 5 argues that the scientific findings about attention and the basic considerations about the evolution of different forms of attention demonstrate that consciousness and attention must be dissociated regardless of which definition of these terms one uses. No extant view on the relationship between consciousness and attention has this advantage. Because of this characteristic, a principled and neutral way to settle disputes concerning this relationship can be presented, without falling into debates about the meaning of consciousness or attention. A decisive conclusion of this approach is that consciousness cannot be identical to attention. The evolution of conscious attention is described, as well as the possible functional roles it may serve. Such roles include the facilitation of empathetic interactions, the formation of language capacities, cross-modal sensory integration, and limiting the contents of awareness.

— Carlos Montemayor and Harry Haladjian

The notion that, in contrast to consciousness, there are a multiplicity of forms of attention that might have evolved from one another at different times is an interesting and novel argument. So far as I know there is precious little comparative (i.e. between species) work on attention. I’d be interested in hearing of anything that the authors might have come across. The term ‘attention’ is certainly used in a number of theories of associative learning and there is tantalizing evidence for forms of attention in octopuses (not much of a surprise) and in bees and flies. I don’t think anyone has examined whether attention in non-mammalian species involves anything other than spatial selection though.

That’s what we found too, Bob. There seems to be very little work examining attention comparatively across species or on the evolution of attention in humans. Leda Cosmides and John Tooby have touched on the evolution of attention in their work (e.g., see Annual Review of Psychology paper from 2013). In addition to the work on spatial attention that aids navigation in bees and other insects, Steven Wiederman’s work on dragonflies identifies some feature-specific neurons that can detect targets in complex situations (e.g., identifying prey among distractors while flying). This would be a good example of neural models of feature-based selective attention in insects, and we could argue that this work also has implications on higher-level object-based attention as well. We go into more detail about this evolutionary issue in a recent paper in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review .

But your observation is correct… there is very little work on the evolution of attention to our knowledge, and this is an important area to develop further. I will post some more about visual attention tomorrow and describe the different varieties that seem to tell an evolutionary story.

Hi Carlos, thanks for the clear and useful summary. It might be helpful to say a bit more about how you define “consciousness” and “attention” for purposes of the book. It seems to me that in order to bring empirical evidence into play, you need to define them in ways that are either operational or can be operationalized. Probably the only way to get completely clear on this is to read the book, but I wonder if you can say a little more about it.

Thank you Bill, this is a good question. One goal we want to accomplish in the book is to avoid verbal disputes and, in particular, to avoid using the empirical evidence in ways that reflect ad hoc definitions rather than the substance of the findings. We define attention, broadly speaking, as a selective processing mechanism (or rather, a group of mechanisms) that enhances and selects perceptual information for executing actions and higher-level cognition, including consciousness. We define consciousness, following Block, in terms of access and phenomenal consciousness. There are ways of collapsing all these definitions by focusing on certain features, as Jesse Prinz does. But we believe that selection at different levels and for different purposes (attention), access to contents and epistemic assessments (access consciousness), and the phenomenal character of experience (phenomenal consciousness) cannot be collapsed into a single process, and that the evidence shows that. Perhaps the most convincing way of seeing that is by looking into the evidence for different kinds of attention (chapter 2) and how they must have evolved at different times (chapter 5). I hope this helps! I will post more about consciousness tomorrow.