Typically hylomorphists discuss their theory historically in terms of what Aristotle, Aquinas, or some other philosopher of the past has claimed. That is not my approach!

The hylomorphic theory I defend dovetails with current work in metaphysics, philosophy of mind, and scientific disciplines such as biology and neuroscience. I argue that there are good philosophical and empirical reasons to endorse hylomorphism’s core notion of organization or structure.

Many philosophers appeal to a notion of organization or structure very like the hylomorphic one without fully appreciating what those appeals imply. They include David Armstrong, William Bechtel, Nancy Cartwright, John Dewey, John Heil, Philip Kitcher, and Michael Ruse.

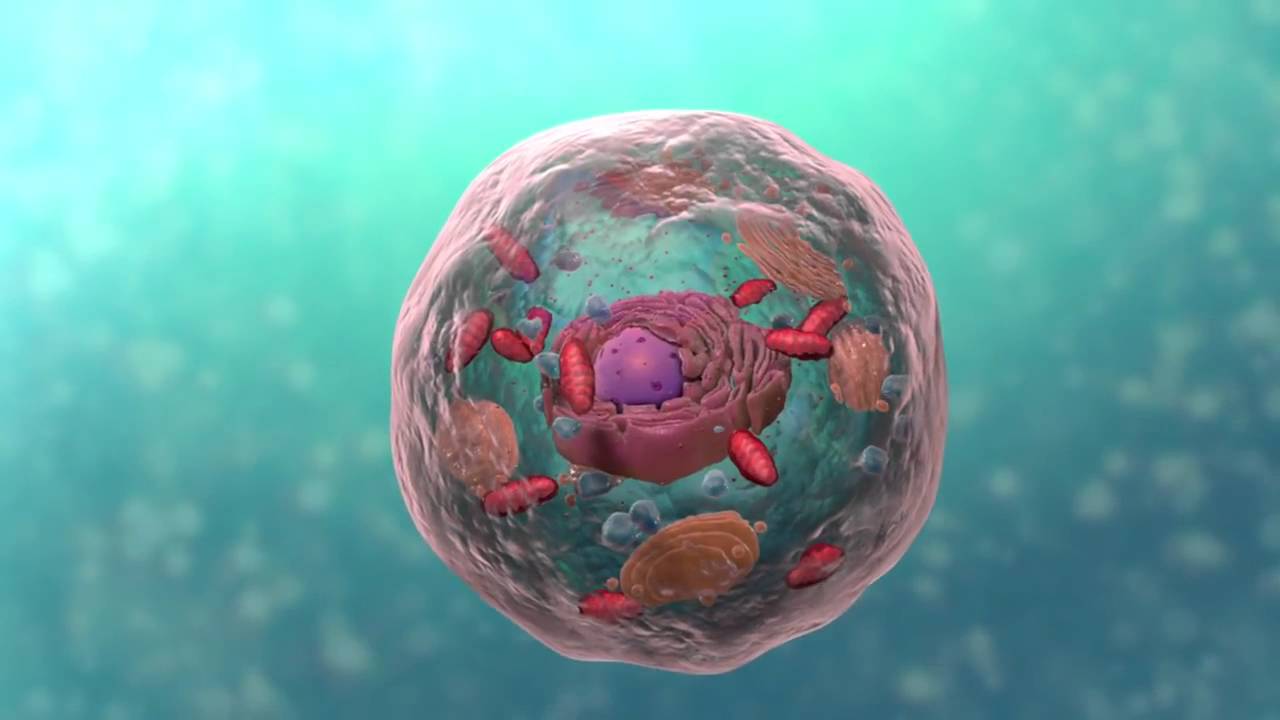

More interesting than the philosophers, however, are the scientists who make frequent appeals to organization or structure in describing and explaining the phenomena they study. Here is one example taken from a popular college-level biology textbook—note the references to organization, order, arrangement, and related concepts:

“Life is highly organized into a hierarchy of structural levels… Biological order exists at all levels… [A]toms… are ordered into complex biological molecules… the molecules of life are arranged into minute structures called organelles, which are in turn the components of cells. Cells are [in turn] subunits of organisms… The organism we recognize as an animal or plant is not a random collection of individual cells, but a multicellular cooperative… Identifying biological organization at its many levels is fundamental to the study of life… With each step upward in the hierarchy of biological order, novel properties emerge that were not present at the simpler levels of organization… A molecule such as a protein has attributes not exhibited by any of its component atoms, and a cell is certainly much more than a bag of molecules. If the intricate organization of the human brain is disrupted by a head injury, that organ will cease to function properly… And an organism is a living whole greater than the sum of its parts… [W]e cannot fully explain a higher level of order by breaking it down into its parts” (Campbell, Neil A. 1996. Biology, 4th Edition (San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings Publishing), pp. 2-4).

This passage suggests that the way things are structured, organized, or arranged plays an important role in them being the kinds of things they are, and in explaining the kinds of things they can do. It suggests, in other words, that organization or structure is an ontological and explanatory principle.

If we are committed to countenancing the entities postulated by our best descriptions and explanations of reality, and we think those descriptions and explanations derive from empirical sources such as the sciences, then scientific appeals to structure make a serious ontological demand. The most direct way of meeting that demand, I argue, is to take scientific appeals to structure at face value—to claim that structure really exists, and that it plays the theoretical roles those appeals imply. We can express those roles with some slogans:

- Structure matters: it operates as an irreducible ontological principle, one that accounts at least in part for what things essentially are.

- Structure makes a difference: it operates as an irreducible explanatory principle, one that accounts at least in part for what things can do, the powers they have.

- Structure counts: it explains the unity of composite things, including the persistence of one and the same living individual through the dynamic influx and efflux of matter and energy that characterize many of its interactions with the wider world.

In Structure and the Metaphysics of Mind I articulate and defend a hylomorphic metaphysic built around a notion of structure that plays these roles. I then go on to show how that metaphysic can be applied fruitfully to solve problems in the philosophy of mind. I outline how it does this in future posts.

Thanks a lot for taking the time to write this up!

This seems very promising. My only worry is about hypostasizing structure as some additional ingredient over and above the biology.

When I say that neural activity is produced by two synaptically coupled neurons, I’m not saying there is some *additional* feature present in the system, a ‘structure’ in addition to two synaptically coupled neurons. The two synaptically coupled neurons *is* the structure. Is this what you are saying, or are you saying there is something else? If the latter, then I’ll be a little worried. 🙂

Eric, thank you for the comment. Let me try to situate the view you describe within the framework set out in the book and draw some distinctions that will address the worry about hypostatization.

Let’s focus on your claim that the two synaptically coupled neurons *are* the structure, where the ‘are’ is presumably the ‘are’ of identity. Let’s call the neurons ‘N1’ and ‘N2’. You say that N1 and N2 are synaptically coupled. Let’s call the synaptically coupled neurons ‘the system’.

Now, with this terminology in mind the first thing to notice is that the claim that the synaptically coupled neurons are the structure will have to be reformulated for two reasons.

First, structures aren’t individuals or collections of individuals. Structures are powers that individuals have.

Second, composition is not the same as identity. A whole is distinct from its parts because it differs from them: it is one, they are many, and a thing can’t differ from itself (for more on this see Peter van Inwagen’s paper ‘Composition as Identity’). So if ‘the system’ designates a single thing, then in a statement of the form ‘the system = X’, the term ‘X’ has to designate a single thing as well (one thing can’t be identical to many). Now, perhaps ‘the system’ isn’t a singular term; perhaps is a term of collective reference like ‘The 2016 Yankees’ as in, “The 2016 Yankees are A-Rod, Eovaldi,…” In that case, however, the ‘are’ is not the ‘are’ of identity; it is more like a way of expressing composition.

Given the foregoing points, here are a two ways of rendering the original claim:

(1) The system = an individual composed of N1 and N2, which are synaptically coupled.

(2) The system = a state of affairs, namely N1’s and N2’s being synaptically coupled.

Depending on which of these claims you endorse, the system will have a structure or not. Endorsing (1) implies that the system is a unified individual distinct from N1 and N2. If that’s the case, the system has a structure, for on the hylomorphic view there can be a unified composite individual only if it has a structure. This is what it means to say that structure counts: it operates as a principle of unity. Diverse things compose a whole only if the whole has a structure that unifies those things: no structure, no composition.

Now, if you think the system is an individual as per (1), then you’ll face a further choice: either (a) you’ll claim that the system’s structure is the synaptic coupling, or (b) you’ll deny this.

If you opt for (a), then you’ll claim that the system is a unified individual which is capable of doing things that N1 and N2 by themselves cannot do, and that it is the synaptic coupling that empowers it to do so.

If you opt for (b), then you’ll claim that the structure that unifies N1 and N2 into a single unified individual (the system) is something different that we haven’t described yet, and synaptic coupling is something else, e.g. a mere spatial relation between N1 and N2 that is maintained by the system’s structure but that isn’t the structure itself.

Suppose, however, you have in mind not claim (1) but instead claim (2). In that case you’ll deny that the system is an individual. In this case, the system has no structure, for if it did, it would be a unified individual distinct from its parts. This is the converse implication of structure counts: diverse things compose a whole if there is a structure that unifies them: no composition, no structure. If claim (2) is what you have in mind, then ‘the system’ is just a shorthand way of referring to N1’s and N2’s standing in the relation of being synaptically coupled. When we take the inventory of the individuals that exist, the system won’t be on the list.

Among the scenarios described by (1a), (1b), and (2), which is the hylomorphist committed to? The answer is determined on broadly empirical grounds. The reason is that whether or not the system is really a unified individual distinct from N1 and N2 depends on whether the system is capable of doing things that N1 and N2 by themselves are incapable of doing, and whether or not this is the case is something that can be determined only by studying what the system does and what N1 and N2 by themselves can do.

Now, let’s turn to the issue of hypostatization. Here the difficulty is that ‘hypostatization’ is ambiguous. What I present in the book are reasons to include hylomorphic structure in one’s ontology – broadly Quinean reasons concerning ontological commitment. If that’s all that ‘hypostatization’ means, then we’re in the habit of hypostatizing lots of things – in fact, most of the things we talk about when we do science. Moreover, we have very good reason to do so. Typically, however, people don’t use ‘hypostatization’ to refer to mere ontological commitment in this sense (I certainly don’t use it that way). Typically it refers to something more robust; for example, hypostasizing an entity, e, might amount to claiming that e is an independently existing substance (something like that is connoted by the Greek term ‘hupostasis’). To hypostatize structures in this sense would be conceive of them along the lines of Platonic forms or Thomistic rational souls which are able to exist disembodied independent of any matter. The hylomorphic theory I defend is opposed to both of these views. Ultimately, though, given the variety of meanings ‘hypostatize’ can have, and the variety of theories that correspond to those meanings, the only way to get clear on this matter is to describe the hylomorphic view of structure and to distinguish it from the alternatives. That’s what I do in the book. In fact, one of my goals is to distance the hylomorphic view I defend from these other views and stake out the minimum ontological commitment needed to make sense of empirical work that posits structure.

Thanks for the response.

Note, for discussion let’s assume that we have two neurons that are coupled in such a way that they generate patterns of activity that they would not generate alone. That is, the synaptic connectivity is necessary to generate patterns, something like in the paper ‘Analysis of oscillations in a reciprocally inhibitory network with synaptic depression’ by Adam Taylor (Neural Computation 2002).

So in this case N1 and N2 are incapable of showing periodic membrane oscillations on their own, but do so when synaptically coupled.

I have granted that the neurons, when coupled, could do things that the individuals could not do by themselves (i.e., oscillate). I’m not sure how this would empirically force us to say the coupled N1-N2 system forms a unified individual (Option 1), rather than simply saying we have two neurons that are synaptically coupled, and the fact that they are coupled explains their oscillatory properties.

The difference between Options 1 and 2 seems razor-thin to me, to the point where I’d be tempted to just go with Option 2 because it seems more parsimonious.

At any rate, to the extent that there is a difference, I’m not convinced that the decision between Option 1 and Option 2 would be empirical, given that I have tried to set up an example to be empirically friendly to Option 1, but I cannot see how it would actually empirically favor Option 1.

Hi Eric,

Let’s focus on this statement: “I have granted that the neurons, when coupled, could do things that the individuals could not do by themselves (i.e., oscillate).” This doesn’t quite address the difference between (1) and (2) – and there is an *enormous* difference between them! It’s a difference in basic ontological categories – the difference between, say, Socrates and winning a baseball game: one is an individual, the other is an event.

Events or states of affairs (the terms can be used interchangeably here) are individuals having properties or standing in relations, e.g. Socrates’ being 6 feet tall. That’s obviously different from Socrates himself since Socrates could’ve been taller or shorter, and since Socrates has other properties besides this one.

Now, importantly, the question is not whether *the neurons* when coupled do things they couldn’t do otherwise; the question is whether *the system* can do things the neurons can’t. Take an analogy: two people can obviously do things that one person alone can’t, e.g. dance a tango. But there’s a difference between saying that persons A and B are dancing a tango, and saying that persons A and B compose a third individual, C.

Consequently, simply saying that the neurons do things when coupled that they don’t do alone doesn’t yet answer the question about whether you endorse (1) or (2). Moreover, if there’s not a clear sense for what conditions are sufficient and necessary for there to be emergent properties that would mark the difference between cases like (1) and cases like (2), then it’s going to remain unclear how to judge in particular cases whether there are emergent properties and hence whether there is an emergent individual. So in this case it’s going to remain unclear whether you should plump for (1) or (2).

Note that the decision between them is not simply a matter of ontological parsimony. Parsimony becomes a factor in theory choice only if the theories being evaluated are roughly equivalent in other respects. We should choose the more parsimonious theory *all other things being equal* (if this weren’t the case, we’d all be Eleatic monists!). But the choice between (1) and (2) can’t presuppose that all other things are equal since the difference between them implies a difference in explanatory power: if the system is a genuine individual, as (1) would have it, and only if it is a genuine individual, does it have emergent properties – powers that can’t be explained by appeal to the operation of its parts alone. Suppose for the sake of argument that this is the case. Then the choice between (1) and (2) becomes a choice between explaining the system’s behavior (namely by appeal to its emergent properties) and failing to do so. Parsimony never enters the picture.

The more basic question is whether the oscillation you mention is a property of the neurons, or whether it is a property of the system. I personally suspect that the former is the case. That is, I suspect that there is nothing to the system other than N1’s and N2’s being synaptically coupled, and that the oscillation you mention is just a manifestation of powers that N1 and N2 by themselves have. I suspect, in other words, that the system is not a genuine individual with emergent structure-dependent properties. But two things: first, I could be wrong about this; it’s just an untutored empirical conjecture. Second, hylomorphists don’t think that everything is like the system as I’ve just conjectured it to be.

Now, maybe hylomorphists are wrong about this last claim: maybe everything is like the system as I’ve just conjectured. In that case, hylomorphism ends up being false; everything can be exhaustively described and explained without appeal to hylomorphic structure. In the book, I consider three views of this sort: structure eliminativism, structure reductivism, and nonreductive structure antirealism. I nevertheless argue that there are reasons to prefer the straightforward structure realism that hylomorphism endorses. The hylomorphic framework, I argue, provides a way of understanding empirical appeals to organization or structure that is superior to these competing views in a variety of respects – including its ability to solve problems in metaphysics concerning composition.

Hi William, thanks for the post. You say:

“If we are committed to countenancing the entities postulated by our best descriptions and explanations of reality, and we think those descriptions and explanations derive from empirical sources such as the sciences, then scientific appeals to structure make a serious ontological demand. The most direct way of meeting that demand, I argue, is to take scientific appeals to structure at face value—to claim that structure really exists, and that it plays the theoretical roles those appeals imply. ”

There seem to be a lot of meta-ontological claims here (e.g. a Quinean realism). To focus on one: taking scientific appeals to structure at face value. Two concerns:

1. a good deal of philosophy of science seems to teach us that it is usually dangerous to take scientific appeals at face value (e.g because good science often makes for bad metaphysics). Rather, a good deal of careful reconstruction of why certain claims are warranted is often required. So why is it appropriate in this case?

2. Your view seems to have a family resemblance to an ontic conception of mechanistic explanation (sidebar: is this actually the core of your view? if not, how/why?). But such a view faces challenges. Example: how do we individuate the start up and termination conditions of a mechanism? A reasonable answer is to say that this is constrained by pragmatic considerations (e.g. explanatory interests). But ostensibly such a move is not open to you (since this move usually coincides with rejecting an ontic view of mechanisms).

Hi JBR,

Thank you for the comments! Regarding point 1: you’re absolutely correct that the view is committed to a broadly Quinean view of ontological commitment. It claims that we’re committed to all the entities needed to make our best descriptions and explanations true and our best scientific methods effective. This conjoined with a broad empiricism is what I call ontological naturalism. Ontological naturalism is the price of admission to the discussion. If someone rejects it, I have nothing to say in response. Philosophical inquiry has to start somewhere.

What I’m not altogether clear about is the implicit premise that a commitment to something like ontological naturalism implies a flat-footed approach to interpreting scientific descriptions and explanations.

There doesn’t seem to be any incompatibility in being an ontological naturalist and carefully interpreting scientific descriptions and explanations with an eye to figuring out exactly which entities those descriptions and explanations commit us to (what you’ve called “careful reconstruction”). By analogy, representing English language sentences in a first-order formal language requires first paraphrasing those sentences in a way that highlights their logical forms. Presumably anyone who wants to apply a Quinean criterion of ontological commitment will have to do something analogous with the descriptions and explanations scientists provide. That’s just the cost of doing business, especially since scientists typically don’t use language in the rigorous ways philosophers demand. So if there’s an issue here, it’s an issue not just for me, but for anyone who takes something like ontological naturalism seriously.

Regarding point 2: The hylomorphic view is committed to an ontic conception of mechanistic explanation, but it would be incorrect to say that that’s the core of the view. The core of the view is the notion of hylomorphic structure. That notion enables the view to do a lot of metaphysical heavy lifting including providing identity and individuation conditions for structured individuals. If mechanisms are among those individuals, then structure provides identity and individuation conditions for them as well.

In fact, however, most of the things people call ‘mechanisms’ are not individuals in the same sense as, say, human organisms since mechanisms depend for their existence on organisms in the strong sense that their identity and individuation conditions include the ways they contribute to the organism’s activities. There’s a lot to be said on this point. I discuss it in detail in Chapters 6 and 7 of the book.

Hi William, thanks for the reply!

Regarding Q1: I think we are in agreement. I was merely responding to your statement that we take scientific claims at “face value”, which is ostensibly not the same thing is critically evaluating them.

Regarding Q2: right, so hylomorphic structure is different than the internal organization of a mechanism, and the sorts of entities you are interested in are not mechanisms. But it seems you have not addressed my ultimate question, which is how you address the role of pragmatic considerations that make ontic conceptions of mechanisms somewhat dubious. Example: what are the boundary conditions for a human organism? In space or time, etc? If the answer is: that depends on your explanatory interest, then we risk a kind of ontological relativism (which I take it is the reason for avoiding an ontic conception of mechanisms). And I take it that (prima facie) one cannot simply point to the hylomorphic structure to answer the question, since the composition of the structure is determined by the explanatory interests/constraints as well.

Hi JBR,

Hmm. I thought I did answer that question. Let me see if I can explain why: (1) If hylomorphism is true, then the conditions whereby structured individuals are identified and individuated by appeal to hylomorphic structure. (2) If mechanisms are structured individuals (and that’s a big ‘if’), then mechanisms are identified and individuated by appeal to hylomorphic structure. (3) If mechanisms are identified and individuated by appeal to hylomorphic structure, then the identity and individuation conditions for mechanisms are not simply a function of our explanatory interests. Therefore, if hylomorphism is true, then the identity and individuation conditions for mechanisms are not simply a function of our explanatory interests.

The crucial premise here is (3). I defend it (albeit in a more general way) in the book vis-à-vis the problem of mental causation. Some critics of the hylomorphic solution to the problem endorse a view of explanation of the sort you appeal to here. Hylomorphism rejects that view of explanation. I describe the alternative in Chapters 10 and 13, and also in a forthcoming paper entitled ‘Hylomorphism, Explanatory Practice, and the Problem of Mental Causation’

Hi William,

Thanks for the reply. Let me put my Q this way: suppose I grant the inference 1-3. My question is: why not think that hylomorphic structures identified by science are themselves interest relative in the very same way that some have thought mechanisms are? I want to know (just a gist really) of why your view does not face the same kind of objection raised against ontic views of mechanistic explanation. To be clear, I am not worried about mechanistic explanation. I was just trying to make an analogy (rereading my last post, I was a bit unclear, and probably introduced more heat than light!)

Hi JBR,

Thank you for the continued exchange. I’m new to the whole blogging thing, and am finding it really fun and interesting thanks to contributions like yours.

I think the thing to say is this: If you grant 1-3, then the objection you mention never gets off the ground. That objection presupposes a metaphysics that is at odds with hylomorphism: it presupposes (contrary to hylomorphism) that the identity and individuation conditions of structured wholes are determined entirely by our descriptive and explanatory interests. Call this the ‘interest-relative view’.

Because hylomorphism denies the interest-relative view, someone who takes the interest-relative view for granted presupposes that hylomorphism is false. As a result, an argument based on that view does not provide a non-question-begging objection to hylomorphism: it doesn’t prove that hylomorphism is false, it rather assumes it from the outset.

Of course, someone is free to reject the hylomorphic view wholesale in favor of the interest-relative view. It’s simply that taking the latter view for granted cannot be the basis of an objection to hylomorphism without begging the question against the latter.

Another way to think of it: the idea that identity and individuation conditions for entities of kind K (mechanisms, structured wholes – whatever) are wholly determined by our descriptive and explanatory interests is not metaphysically innocent. The interest-relative view stakes out a very particular metaphysical position on the nature of Ks or K-discourse. Hylomorphism stakes out a very different position.

If we were to stick only to the dimensions of the conversation as we’ve sketched them thus far, then the discussion would grind to a halt because one side’s modus ponens would simply be the other side’s modus tollens: hylomorphists would argue modus ponens to the conclusion that the interest-relative view is false, and exponents of the interest-relative view would argue modus tollens to the conclusion that the hylomorphic view is false.

But we need not – and indeed cannot – stick to the dimensions of the conversation we’ve sketched thus far. The reason is that there’s more at stake in the disagreement between hylomorphism and the interest-relative view than their implications for a philosophy of science. There’s also a range of vexing issues in metaphysics that need to be addressed concerning, among other things, the nature of composition, of properties, of powers, and so on.

I argue in the book that there are good reasons to endorse hylomorphism because of the way it handles these issues. An alternative metaphysical framework is going to have to handle these issues at least as well as hylomorphism does. I have no argument that this can’t be done; although I do survey a range of alternatives and argue that they fall short in various respects. The important point vis-à-vis people who would advance the kind of argument you mention is that there’s more at issue than they initially grant.

Yet another way to think about it: philosophical inquiry has to start somewhere, but it’s always open to our interlocutors to challenge our starting points. When that happens we can do one of two things: first, we can opt out. That’s, for instance, what I’m more or less forced to do at this point if someone challenges the ontological naturalism I mentioned in a previous post. At this point, I really have nothing to say to those challenges, so I’ve really got no choice but to just stop. Second, we can opt to stay in and continue the discussion. But that can happen only if we find some way of addressing the challenges.

In the same way, hylomorphism represents a challenge to the implicit starting points of the kind of objection you describe. So someone who wants to continue defending the interest-relative view is going to have to find some way of addressing the hylomorphic challenge, and that’s going to mean delving into the metaphysical issues that hylomorphism looks to address.

Hi William,

Thank you for the great reply—I apologize for not responding sooner!! I will try to say something brief. You say:

“That objection presupposes a metaphysics that is at odds with hylomorphism: it presupposes (contrary to hylomorphism) that the identity and individuation conditions of structured wholes are determined entirely by our descriptive and explanatory interests. Call this the ‘interest-relative view’.”

Actually, I do not believe my question presupposed this. I was taking it for granted that metaphysics is not interest-relative.

My point was that what we take to be the boundary conditions for the purpose of explanation are often interest-relative (because of the predictions we want to make; things we want to explain), or so it has been argued (e.g. with mechanisms). In which case, an ontic view of these partially interest-relative posits would lead to an interest-relative metaphysics (which is of course not the one we want).

So I wonder: why not think that the boundary conditions of hylomorphic structure are in part relative to our explanatory interests? An example: there is genetic “structure”; but you don’t have to push very hard to see that what the “unit of selection” is depends in part on the explanatory question you are asking (see e.g. phi sci discussions of the concept “gene”). This amount of interest-relativeness seems more metaphysically bearable, the less ontological weight you put on the structure. But it seems you put all your weight on this (or perhaps other) kinds of structure identified by science.

So either you agree with the above kind of interest-relativeness, but think it isn’t a problem for your view, in which case, I was wondering as to the argument. Or, you disagree, in which case, I’d like to know why you think there isn’t this kind of interest-relativeness when it comes to positing hylomorphic structure. But I do not think there is any question of question-begging here.

Hi JBR

Thanks for the response. I think we’re making progress here. There are several things to say.

Let’s start with this: “[A] what we take to be the boundary conditions for the purpose of explanation are often interest-relative… [B] In which case, an ontic view of these partially interest-relative posits would lead to an interest-relative metaphysics.”

Claim (A) is ambiguous. Let’s distinguish these two claims:

(A1) The identity and individuation conditions for the things that exist are often interest relative.

(A2) When we explain something, we focus on a select range of factors that contributed to the explanandum and ignore the rest, and what we choose to focus on is a function of our explanatory interests.

Given the ambiguity in (A), claim (B) can be interpreted in either of the following ways:

(B1) If the identity and individuation conditions for the things that exist are often interest relative, then what things exist is interest relative (i.e. we get an interest-relative metaphysics).

(B2) If, in explaining something, we focus on a select range of factors that contributed to the explanandum and ignore the rest, and what we choose to focus on is a function of our explanatory interests, then what things exist is interest relative (i.e. we get an interest-relative metaphysics).

We thus get two arguments to the effect that what things exist is interest relative based on the following conjunctions of premises:

Argument 1: A1 & B1

Argument 2: A2 & B2

In response to these arguments, hylomorphists reject A1 and endorse A2, and they reject B2 and endorse B1. I’ve touched on hylomorphists’ reasons for rejecting A1 in my previous posts. They are committed to B1, however, because they reject A1, and A1 is the antecedent of B1. Let this suffice for Argument 1.

Let’s turn to Argument 2. Hylomorphists reject B2 because they reject any inference from the selectivity of our explanatory modes (as described in A2) to the conclusion that what exists is interest relative. The idea that it is possible to make this kind of inference presupposes that different kinds of explanations map onto disparate inventories of entities that make those explanations true, i.e. they presuppose an interest-relative metaphysics. But hylomorphists reject this presupposition for reasons I’ve already discussed.

Perhaps it’ll help to say more about these points. Let’s start with the account of explanation that endorses A2 while rejecting A1.

On the hylomorphic view, the world is saturated with causes and causal relations of many different kinds. For example, there is a whole range of different factors that cause a car crash: the balding tires, the faulty brake mechanism, the insufficient roadway grading, inadequate signage warning drivers of an impending curve, the driver’s blood-alcohol level—all of these factors and more contribute to the crash.

These factors and the diverse ways they contribute to the effects belong to what J. S. Mill would call the crash’s “complete cause”. In most cases, however, we’re not concerned with describing something’s complete cause. We’re interested in only a select handful of contributing factors. We focus on the ones that suit our interests in a given context and ignore the rest. The automotive engineer focuses on the brake mechanism, the civil engineer on the roadway grading, the prosecutor on the blood-alcohol level, and so on. David Lewis expresses the idea as follows:

The multiplicity of causes… [is] obscured when we speak, as we sometimes do, of the cause of something. That suggests that there is only one . . . If someone says that the bald tyre was the cause of the crash, another says that the driver’s drunkenness was the cause, and still another says that the cause was the bad upbringing that made him reckless, I do not think that any of them disagree with me when I say that the causal history includes all three. They disagree only about which part of the causal history is most salient for the purposes of some particular enquiry. . . (‘Causal Explanation,’ pp. 215–16).

Which factors we select for attention is doubtless a function of our subjective interests. But importantly, making a selection among objective causal factors does not make them or the contributions they make to their effects any less objective. The balding tires, the faulty break mechanism, the shallow roadway grading, the high blood-alcohol level—these and other factors contribute to the car crash in objective, external, mind-independent ways. Choosing to focus on one factor or the other doesn’t change that.

Which factors we choose to focus on is reflected in the logic of explanation. Explanations are answers to certain sorts of why- and how-questions. The logic of those questions constrains the kinds of responses that count as answers – a principle of erotetic logic known as Hamblin’s dictum. Based on the work of Belnap and Steel (The Logic of Questions and Answers), van Fraassen has outlined a logic of why-questions in Chapter 5 of The Scientific Image, and I’ve outlined a logic of how-questions in ‘The Logic of How-Questions’ (Synthese 2009).

The upshot of these analyses is that when we ask a why- or how-question of the relevant sort, i.e. when we ask for an explanation of something, we are forced by the logic of the question to make a selection among a range of contributing factors. In the logic of why-questions, for instance, this is expressed through the question’s contrast class and relevance relation. To take van Fraassen’s example, the following questions request different kinds of information about the same event:

Q1. Why did Adam eat the apple (in contrast to the pear, or the mango, or the strawberry, or…)

Q2. Why did Adam eat the apple (in contrast to having thrown it away, or chopped it up, or…)

It is thus possible to ask a range of different why- and how-questions, i.e. to request a range of different explanations, about a single individual, property, or event. This is the case because every individual has many different properties that empower it to interact with other individuals in many different kinds of ways. As a result, the events that occur always comprise a plurality of explanatory factors only some of which interest us on any given explanatory occasion.

This is how hylomorphist understand the “interest-relativity” of explanation. Notice that, for the reasons just stated, this understanding doesn’t imply that what entities exist is a function of our explanatory interests. On the contrary, it presupposes the interest-independence of the factors that contribute to any potential explanandum. That is why the account also rejects B2: making a subjective selection among objective contributing factors doesn’t make those factors subjective.

We can come at all this by appeal to an example of the sort you suggest: suppose that some people speak of genetic structure. Does this commit hylomorphists to positing genetic structure? The answer is No, for several reasons.

First, not just any old talk of structure corresponds to hylomorphic structure. To take just one example: people refer to mere spatial arrangements of physical materials as structures all the time, but mere spatial arrangements aren’t structures in the hylomorphic sense. With this in mind, consider what the expression ‘genetic structure’ is supposed to refer to.

The only things with structures on the hylomorphic view are individuals and their activities. If ‘genetic structure’ is supposed to refer to a structure in the hylomorphic sense (and that’s a big ‘if’), then it’s going to have to be either the structure of an individual or the structure of an individual’s activity.

Now, let’s imagine that someone claims that it is the structure of an individual – a gene, say. We can then ask: what makes a gene the kind of individual it is, and what distinguishes it from other individuals of the same kind? If someone responds that all this is very unclear, then it is equally unclear that there really are genes. And if it’s unclear that there really are genes, then it is equally unclear that there is anything there that has a hylomorphic structure.

But wait a minute, someone will say, I thought that according to hylomorphists which individuals and structures exist was to be determined by appeal to science, and yet when we look at the science some people say genes are the things that do X, others say genes are the things that do Y, others say the things that do X are identical to the things that do Y, and yet others deny this. Why isn’t this a problem for hylomorphists?

The answer starts here: if hylomorphism is true and the interest-relative metaphysics discussed in previous posts is false, then there are joints in nature: individuals and properties that exist independent of any particular interests we have in them. Let’s now combine this with a philosophy of science according to which the job of science is in part to discern those joints. We can then distinguish two stages of scientific progress: a stage at which we’ve succeeded in discerning the joints, and a preliminary stage at which we’re still fumbling around trying to find them.

Given this framework, hylomorphists would look at the foregoing disagreements about genes and conclude that the science is still at a preliminary stage, that we still haven’t succeeded in discerning which individuals and properties are genuinely responsible for the phenomena that interest us.

The hope is that this is just a passing phase. If it’s not, then one of two things is the case. First, it could be the case that the interest-relative metaphysics is true. We’ve nevertheless agreed to rule this out ex hypothesi. That leaves the other option: there are certain limitations in our cognitive abilities or in our scientific communities (or whatever) that will forever prevent us from discerning where the joints in nature really are even though there are such joints.

With the foregoing points in mind, let’s suppose that someone were to object to the hylomorphic view that it’s unclear what structures exist because there are disagreements of the foregoing sort: if we’re interested in explaining X, then it looks like there are structures of one sort, but if we’re interested in explaining Y, then it looks like there are structures of some other sort, and so on.

The hylomorphist responds that with time, effort, good luck, and whatever else successful scientific endeavor takes, this will all get sorted out. Someone who rejects this sanguine attitude either endorses the cognitive limitation view mentioned above or else the interest-relative metaphysics. But the cognitive limitation view is compatible with hylomorphism, so it doesn’t constitute an objection to it, and the interest-relative view we’ve agreed to put to one side. In that case, however, the objection goes by the boards.

Hi William,

Thank you for the excellent response (and please excuse my slow reply!) I agree that the two alternatives I described were ambiguous, as you say. And I think the way you argue that hylomophism addresses the challenges is compelling.

Where I think I get off the wagon is made salient by your comment about genes. Perhaps, as you suggested previously, there is a foundational disagreement after all, since I do not think it is a passing phase, nor do I think it reflects our intrinsic cognitive limitations. Rather, I think the interest-relative explanation is the most compelling (likewise for metaphysical claims about the non-existence of phlogiston, vital essences, etc.)

Thanks again for the response.