Today—in my (alas!) last posting—I suggest some ways the account of the evolution of representational decision making laid out in my book (and sketched in outline last time on the blog) can be applied to a number of open questions in philosophy, psychology, and economics. I will focus on three questions: the extent to which decision making is intertwined with the organism’s environment, the generality of the decision rules the organism relies on, and the circumstances in which there is reason to think that organisms are altruistically motivated to help others.

The extendedness of decision making (and cognition) is a much-discussed topic in philosophy and cognitive science (including on this blog!). Generally, the extendedness of decision making refers to the idea that features of the organism’s environment are integral parts of the very process of decision making. It is furthermore typically thought that a commitment to the extendedness of decision making implies a rejection of the fact that decision making is representational. One way to summarize this is by means of the following argument:

(1) Representational decision making is costly (in terms of time, concentration, and attention).

(2) Externalized, non-representational decision making avoids the costs of representational decision making.

(3) Ceteris paribus, evolution by natural selection favors less costly over more costly decision-making processes.

Therefore:

(4) Much decision making should be expected to have evolved to be non-representational and extended.

However, for two reasons, this argument is unconvincing. On the one hand, this argument fails to take into account the benefits of representational decision making: as pointed out in the last blog post, these include an increased ease in adjusting to changed environments, and a streamlined cognitive and neural system. On the other hand, this argument is based on a false contrast. Features of the organism’s external environment can lessen the costs of representational decision making, too. For example, organisms can use the environment to store intermediate steps in their representational inferences, or they can rely on a division of labor, where some organisms solve one part of the overall inferential problem, others another, and they then communicate their respective solutions to each other. Knowing something about the factors that influence the evolution of representational decision making provides information about when and why these externalized ways of making representational decision making should be expected to be instantiated.

A second application of the account of the evolution of representational decision making concerns the question about the generality of the decisions rules that organisms should be expected to rely on. On the one hand, there are those—like Gerd Gigerenzer and the ABC Research Group[1]—that suggest that organisms rely on a large number of specialized decision rules. By contrast, defenders of a more generalist account of decision making suggest that organisms rely on just a few highly general rules (such as expected utility maximization) in all cases.[2] What the account of the evolution of representational decision making laid out in my book can do here is suggest when we should expect decision making to rely on more general rules, and when on more specialized ones. In fact, it turns out that this contrast can be seen as a scaled version of the contrast between reflexive and representational decision making.

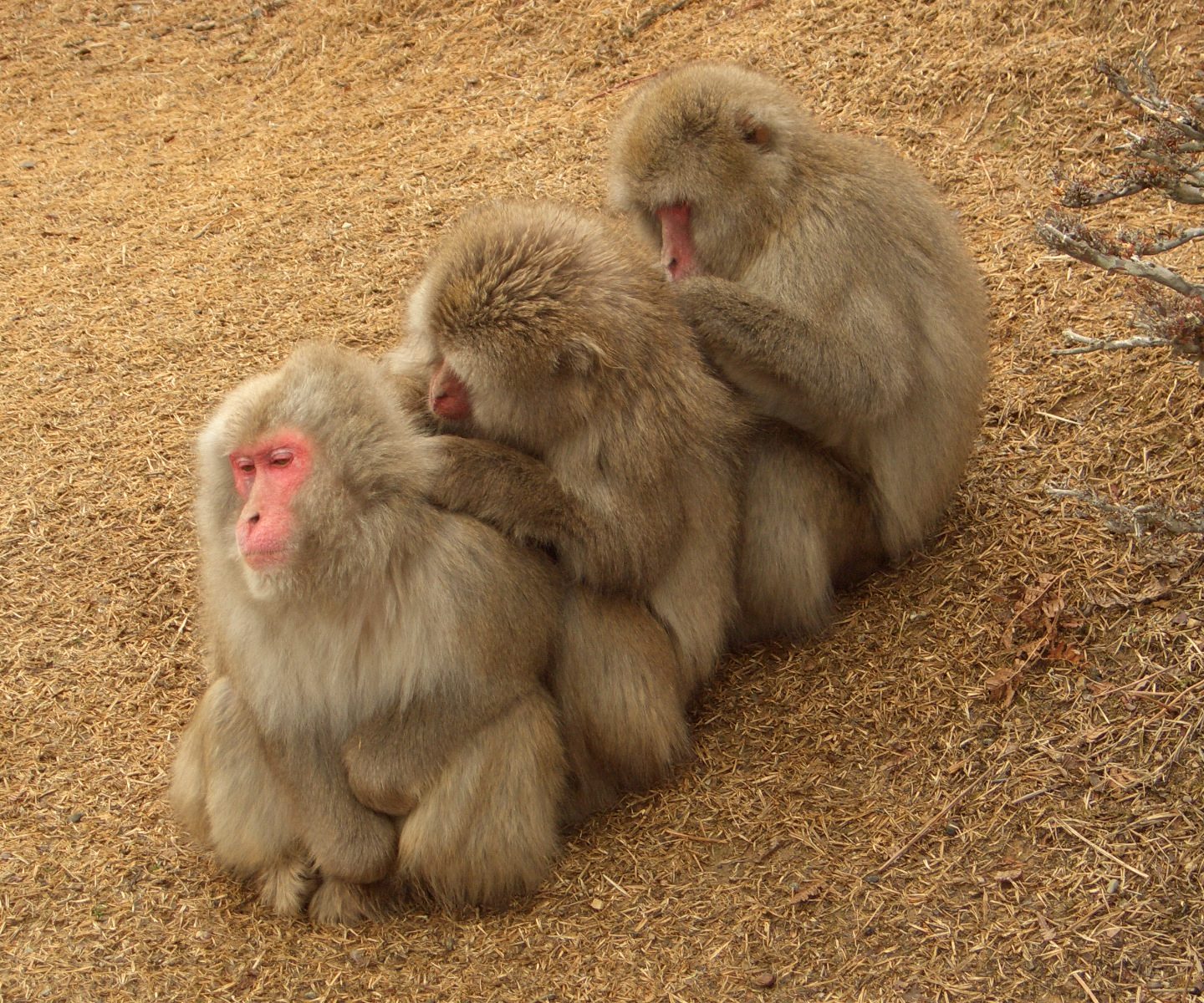

Lastly, consider the discussion surrounding the question of whether and when humans (and other organisms) are altruistically motivated to help others—i.e. by a genuine concern for the well-being of the other organism. When placed in the present context, it becomes clear that this issue can be seen as an instance of the question of when organisms should be expected to rely on a specialized decision rule for helping (certain) others, and when on a general decision rule to further their own interests (which may entail helping others in certain circumstances). Knowing something about when representational decision making with different degrees of generality is adaptive—as in the prior application of the theory—can thus tell us something about when we should expect organisms to be altruistically motivated.

All in all, therefore: the evolution of representational decision making is a fascinating topic of research with important applications to other questions. It also shows that providing a moderate, but still substantial form of evolutionary psychology is possible.

[1] G. Gigerenzer, P. M. Todd, and ABC Research Group, Simple Heuristics That Make Us Smart (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

[2] See e.g. P. W. Glimcher, M. C. Dorris, and H. M. Bayer, “Physiological Utility Theory and the Neuroeconomics of Choice,” Games Econ Behav 52, no. 2 (2005).

An amateur question from an amateur (apologies if this makes no sense):

Based on your posts here, I extrapolate you, coupled with other social science evidence, to generally suggest that thinking and behavior in mainstream retail politics is more non-representational than not. If that’s true, does that suggest that modern complex societies are beyond the ability of ordinary people to apply representational thinking to politics in anything more than a rudimentary or very limited sense?