A number of factors make the problem of consciousness seem harder than it is. I will say something briefly about two of them here.

One is that people the world over are tacit dualists about the mental, making them much more receptive towards non-physical qualia than they otherwise would be. Until recently, with the advent of modern science, all people in all cultures have believed in an ontological separation between mind and body. Arguably these beliefs are facilitated by an innate or innately channeled mindreading system. Moreover, like people’s tacit beliefs in many other domains, there is evidence that they aren’t discarded when one consciously embraces physicalism about the mind, but continue to operate in the background, influencing one’s thoughts and behavior outside of one’s awareness. The result is that people place far more credence in philosophers’ thought experiments (zombies, color-deprived Mary, the explanatory gap, and so on) than they otherwise would (or arguably should). This is because the conclusion of such arguments—qualia realism—serves to confirm their tacit dualism about the mind. Hence even if, on reflection, they decline to accept that conclusion, they pay it more respect than they otherwise might. (Ask yourself: In what other domain do scientists take philosophers’ thought experiments so seriously?)

A second confounding factor in debates about consciousness is terminological confusion. Here philosophers can really help. We have distinguished a number of different notions of consciousness, or a number of different ways of using the term “conscious.” The primary target of explanation is phenomenal consciousness, of course, which is about the introspectable feel of our experiences—what they are like. This notion is basically first-personal. All public talk about what experiences are like is really just an invitation to others to pay attention to their own states to verify what is being claimed from reflection on their own case.

Famously, phenomenal consciousness can be distinguished from access consciousness, which is a functionally-defined third-personal concept. Access-conscious states are those that are available to inform reasoning, decision making, verbal report, and for formation of long-term memories. Both phenomenal and access consciousness are properties of mental states, however, and hence both can be distinguished from uses of “conscious” to characterize an agent. We can say that someone is conscious as opposed to asleep. And we can say that a creature is conscious of something happening in the environment, meaning that they see, hear, or otherwise perceive it.

Each of these four notions can be pulled apart from the others in application. For instance, there can be states that are both access-conscious and phenomenally conscious in an agent who is unconscious, as when one dreams. And agents can be perceptually-sensitive to their environment in the absence of either form of mental-state consciousness, as in cases of sleep-walking (or even sleep driving), and in online action-guidance by the dorsal sensorimotor system. Yet it is common for people engaged in consciousness research to move illegitimately—without supporting evidence or argument—from a claim about one of these forms of consciousness to a claim about another.

When we turn to consider the question of phenomenal consciousness in non-human animals, these conflations become especially egregious. Almost all animals have sleep / awake cycles; so almost all are sometimes conscious as opposed to asleep. And almost all animals display perceptual sensitivity to their environment, and can thus be said to be conscious of objects and events around them. Moreover, many animals, in my view, have mental states that are to some significant degree access-conscious, that are available to processes of decision making, simple forms of reasoning, and for formation of long-term memories. None of this settles the question of phenomenal consciousness in animals, however. For that we need a theory of what phenomenal consciousness is, or at least what its cognitive / neural correlates are. And since phenomenal consciousness is first-personal in nature, the theory needs to be devised to cover the case of human consciousness in the first instance. I’ll make some remarks about that tomorrow.

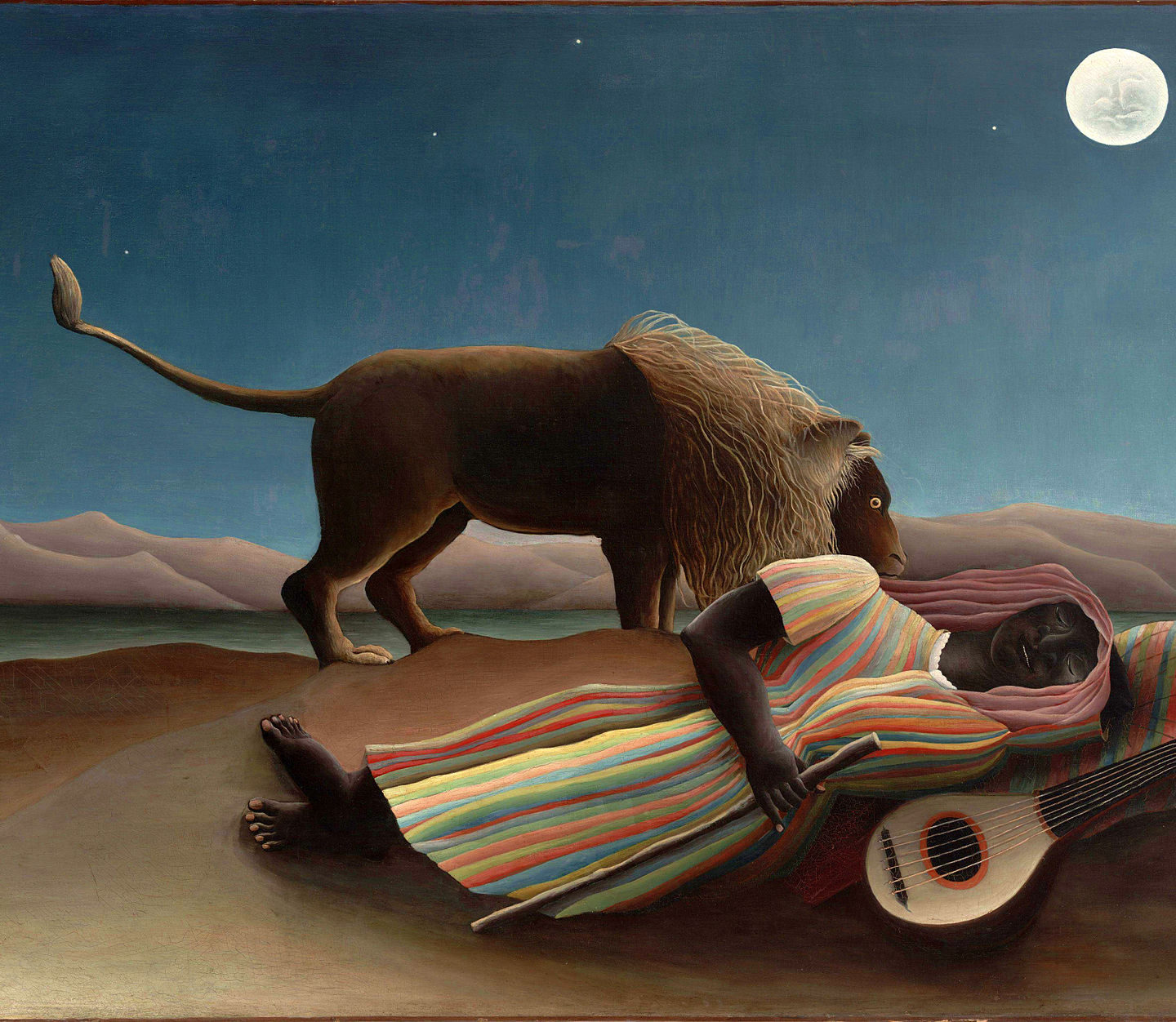

Header image: Henri Rousseau, The Sleeping Gypsy (La Bohémienne endormie), 1897.

Phenomenal consciousness could be compared with a theory of cloud formation into sensible shapes; a thousand factors might be behind movement of clouds in the sky, like what causes each living being to keep phenomenal consciousness.In what way it is important for Philosophy to be know the content of each mind?

What is said above can be applied generally to the very concept of consciousness. It is a term Science started using to degrade the concept of mind,as explained in the following study; https://hiddenobserveronthelimitationsofmind.blogspot.com/2018/01/an-attempt-to-describe-origin-and.html?m=1

A bit more serious study on the subject is here: https://unrecognizedobjectsofthemind.blogspot.com/2019/06/concepts-of-self-realization-and.html?m=1

In short, consciousness is trrm,a subject originated by scholastic Philosophy with least concern on what it exactly is; it is one of the hundreds of functions of mind!

I think the idea that phenomenal consciousness and access consciousness are separate things, rather than the same thing from different perspectives, is itself a holdover from dualistic thinking. Phenomenal consciousness is arguably access consciousness from the inside, and phenomenality is present or absent to the extent that access is present or absent. Which implies that animals have it, albeit in widely varying degrees.

SelfAwarePatterns: I agree with you on the first point, subject to a qualification. (The qualification has to do with access-conscious conceptual information, which I don’t think makes a distinctive contribution to phenomenal consciousness.) And, like you, I used to assume that if phenomenal consciousness is access-conscious nonconceptual content seen “from the inside”, then phenomenal consciousness will be widespread among animals. For a sketch of the arguments why that conclusion neither follows nor should be endorsed, see the posts coming up later this week.

It’s probably worth noting that although phenomenal and access-consciousness as described here can be roughly theoretically distinguished, they are not in practice usually totally distinct and/or separate phenomena. Rather it seems moments in consciousness exist not only on a spectrum of these categories, but also feed off of each other, i.e., your access-conscious decisions and feelings are informed by phenomenal insights and vice versa.

It’ll be interesting to see how you tie this to non-human animals, as it seems to me right now that the clear epistemological hurdle to knowing anything about phenomenal consciousness in animals would be that we typically convey such states to each other via language. At the moment I’m not sure I can imagine anything beyond conjecture and projection to theorize its existence in animals, even though I think there is much reason to assume it most likely does, if simply based on evolutionary theory… so I’m looking forward to your next post.

To avoid terminological confusions, perhaps self-consciousness could be introduced.

Self-consciousness, understood as the capability to think about oneself, is needed by phenomenal consciousness (it is used when we introspect to address the what-aboutness of our mental states).

Should self-consciousness be part of the ‘consciousness problem’?

I’m looking forward to your coming posts.

Christophe, self-consciousness is necessary for phenomenal consciousness to become a problem. But it is question-begging to say that it is required for phenomenal consciousness itself. Indeed, this presupposes the correctness of some variety of HoT theory of consciousness, which is deeply problematic. But you are right that the problem of consciousness emerges out of the distinctive way in which we can think first-personally about our own experiences, as I will explain briefly on Wednesday. And that requires self-consciousness. But I don’t think self-consciousness itself (the capacity to think about one’s own mental states, generally referred to a “metacognition”) is especially problematic philosophically, though there are hard questions about the evidence required to demonstrate its presence in other creatures.

Peter, perhaps the usage of HoT can be avoided by an evolutionary approach in which our non self-conscious ancestors have developed the performance of identification with conspecifics, represented as existing in the environment. Identifications were on seen hands, heard shouting, feelings of perceived emotions, actions on the environment,… By this process our ancestors may have progressively acquired a representation of their own entity as existing in the environment. This could have been the source of an elementary version of self-consciousness. See https://philpapers.org/rec/MENPFA-4 (We may have talked on that some time ago).

Regarding self-consciousness in other creatures, the huge anxiety increase coming from identifications with suffering or endangered conspecifics may have inhibited the evolution toward self-consciousness of our ape cousins. Also, an evolutionary approach may avoid the need of a pre-reflective self-consciousness, as self-consciousness it is not then about turning consciousness to oneself (an abstract for ASSC 24 is to come on that subject).

Can we create a good theory of consciousness that leaves the question of nonhuman animal consciousness open and the question of human consciousness closed without begging the questions? If the theory is based on what we know about humans, it may too quickly close the question wrt other beings, since humans share many properties that might be irrelevant to consciousness (like language). If the theory is based on our best science of the day, then it assumes animal consciousness, insofar as the science of consciousness studies presumes the consciousness of the monkey research subjects used. Given the problem with these two options, I think a theory of consciousness is a premature approach to answer questions about animal consciousness. The science and the philosophy instead needs an analysis of the consciousness concept that allows us to identify plausible exemplars of conscious systems. This epistemic rule can’t be as simple as Newton’s rule, given empirical plausibility of multiple realizability and our knowledge in different domains that the same effects can be caused in different ways. I think we really need a reset in the discussion of animal consciousness.

Kristin, I think you are running together different notions of consciousness here, as so frequently happens in the literature. Phenomenal consciousness is first-personal. All public talk of it is basically just an invitation to others to pay attention to their own mental states to verify what is being said. So scientific investigations have to start from the human case, as indeed they do. When monkeys are used in consciousness research they are used to test claims about perceptual-consciousness and/or access consciousness. For example, the finding that face-selective neurons in monkey prefrontal cortex are active in conditions of binocular rivalry under purely-passive viewing conditions only when the face-image is dominant demonstrates that the PFC activations we find in humans in similar circumstances aren’t a result of response-preparation, thus providing support for global workspace theories. But for the experiments to provide such support, it doesn’t have to be supposed that the perceptual states of the monkey are phenomenally conscious ones.

It also doesn’t have to be supposed that anyone except me has phenomenal consciousness. When and how did the Other Minds problem get solved empirically for other humans? If it did get solved empirically, why can’t it be solved for non-humans? And if it did not get solved empirically, then what is the basis for giving humans, and only humans, a pass on it? Would Neanderthals and Denisovans also get a pass (were they still around), or just members of Homo Sapiens?

Carrie, no one is solving the problem of other minds empirically, so far as I can tell. It sits on the shelf next to the problem of the external world. We don’t need to solve radical skeptical worries to do physics or psychology. The issue is which sorts of subjects should be used in the scientific study of consciousness. If our sample is biased, our results will be biased. If we use only humans to study a phenomenon that exists outside of humans, then our conclusions will be limited, akin to using only male subjects in a study of heart disease. Since the neuroscientist cannot be their own subject, they have to presume someone else is conscious. 🙂

Carrie, thank you for your thoughtful contribution to the discussion.

The problem of other *minds* is solves via an inference to the best explanation. And indeed, this same inference works for animals, including invertebrates, in my view. (The problem also presupposes a first-person-first account of knowledge of minds in general, which is false. See Carruthers [2011] *The Opacity of Mind*.)

The problem of others’ *phenomenal consciousness* is also solved via an inference to the best explanation — in fact the same inference as solves the problem of zombies. (See my post #3 & ch.6 of the book.) This is that we know other humans (and supposed zombies) have the same mental architecture as oneself, with the same consumer systems for globally broadcast nonconceptual content. And we know that they, too, can conceive of zombie versions of themselves. This enables us to conclude that the counterfactual projecting my first-person phenomenal concepts into their minds (viz. “if the dispositions underlying my use of *this feel* were to be instantiated in the mind of the other, they would issue in a judgment that they, too, have states like *this*”) is true.

I don’t think we yet know enough about the minds of Neanderthals to be completely confident that the above counterfactual is true in their case. But there is significant evidence that they have the sorts of capacities required.

In contrast, I think it is pretty clear, on current evidence, that monkeys lack those capacities, and hence the antecedent of the counterfactual requires monkey minds to be quite other than they are, making the counterfactual when targeted at monkey minds as they *actually* are unevaluable.

But the larger point is that it doesn’t matter. Once one accepts that no extra property comes into the world with states like *this* (phenomenal consciousness), then the question whether we can project our first-person concepts into minds significantly unlike our own doesn’t address anything substantive about those minds.

HI Peter and Kristin,

I thought maybe I was too late to the party, so thanks for your responses. I assumed everyone reading this blog would know that I know that no one is solving the Other Minds problem empirically. (I should add, for now — I’m not a mysterian.)

My objection was/is what follows from this. I will use Peter’s monkey example.

We do *not* have better reason to make an IBE to other humans but not to other primates (etc.) unless we already assume that we do. “Same mental architecture” means overlooking differences between individual brains and behaviors in order to get the IBE conclusion for others, but “others” must be species-neutral if the question is not to be begged. So what counts as sufficiently similar for this epistemic purpose? The standard cannot presuppose that all humans are sufficiently similar (to me) but all nonhumans are not, such that the IBE goes through for the humans but not the nonhumans. A speciesist criterion simply begs the question. The empirical data won’t determine what similarity matters or how much. But if one approach the question with the conviction that all humans have phenomenal consciousness (/are sufficiently similar to me) but monkeys etc. don’t (/are not sufficiently similar to me), we will get a foreordained result. I object to that. I also object to having one epistemic standard for humans and a separate higher bar for nonhumans, but I suspect that amounts to the same objection.

Carrie your questions are very helpful and I really enjoyed your work on mental predicates that you summarized here recently.

I am curious if you think it is a good move to accept the human as some kind of exemplar for mentality, and constrain ourselves to an IBE model of discovery/explanation when it comes to other species? This seems much too Cartesian. Let’s say through a model systems approach we discover some mental machinery X in rats. We then find X in other species (e.g., primates). There is no IBE, there are just standard mechanisms of discovery, like we have with the study of the distribution of photosynthesis, or respiration, or whatever.

That is, why give special status to any mental predicates just because we discovered them in ourselves first? I’m thinking of taking a more Second Philosophical approach to all this (Maddy). I get it that there are all these Mary-Zombie-Bat-gap arguments/intuitions that consciousness is special, that it cannot be discovered in other species the way that (say) memory can. I’m pushing to consider that it is premature to accept these Cartesian arguments/intuitions.

Hi Eric,

thanks and good to hear from you. This is Peter’s space so I’ll be brief in my responses and feel free to contact me directly. to answer your questions:

1. no it is not a good move.

2. no we shouldn’t give ourselves special status in this way.

But yes, these are the issues I am working on right now. So stay tuned.

When we say GWT is the best defended theory of phenomenal consciousness, and some of that evidence relies on monkey subjects, directly or indirectly, the problem I raised above exists. The reason monkey subjects are used for studies of phenomenal consciousness is that language isn’t the only invitation to pay attention to first personal phenomenology; a broader range of behavior can serve the same function (as always, I will note that language is simply one type of observable behavior). For ethical, philosophical, and scientific reasons, it’s important to be clear that scientists working on the question of *phenomenal* consciousness are indeed using nonhuman animal subjects, and that was part of the plan from the beginning. For example, in Crick and Koch’s 1990 manifesto for a science of consciousness they called for the use of mammalian subjects, assuming that “higher animals” have the essence of consciousness. Note that Crick and Koch are not concerned with access consciousness; in their definition by example of consciousness they include pain, emotions, self-consciousness, along with vision.

Kristin, what cognitive scientists *think* they are investigating and what they are actually providing evidence for are two different things. And this is especially true in the field of consciousness studies, where the terminology is such a mess. (See my post above, and ch.1 of the book.) If one is to take seriously the first-personal nature of the very notion of phenomenal consciousness — as one must, if one is to stand any chance of addressing the “hard” problem — then we have no option but to start from the human case. One can, of course, learn (a lot) from animal studies about the underlying third-personally characterized architecture. But this is really about perceptual-consciousness / transitive-creature-consciousness and/or some variety of access-consciousness. Whether or not these are the same thing as phenomenal consciousness is, of course, precisely one of the questions in dispute. As for the definition-by-example with which you conclude: each of those things admits of unconscious varieties!

Consciousness is far more complex. To start with it defies basic laws of physics and it defies philosophy. Possibly therefore it is para philosophy and para physics. My first book was entitled “In search of consciousness and the theory of everything ” and there are two more books coming simultaneously to complete as far as possible the topic of consciousness in the context of the origin of the universe and of the theory of everything. The very elusive nature not only of what is but of attempts at describing consciousness tells us that consciousness is paranormal. My theory if consciousness cannot escape the feeling that consciousness is part of the metaphysics of existence.

The main problem, of course, is that phenomenal consciousness is scientifically unobservable. Therefore, assuming it is real, claims about its emergence from the brain are highly problematic, to say the least. Do unobservable properties emerge from observable systems? I don’t think anyone’s ever shown that to be true. As Liebniz understood long ago, there is no observable mechanism for generating unobservable properties. So… if you trust science above all else, it must be an ‘illusion’. There is no consciousness, none this is actually happening, and you are deluded. One wonders though, how consciousness can be an illusion when its contents — such as science and logic — are not.

If humanity can get off of the antidepressants … they would start to let the peinal awaken and understand we are all star seeds of this beautiful universe…. its time to be awakened and raise your vibration to the 4th and 5th densities… yrs trly Trevor

I find the opening paragraph extremely interesting. I think there are definitely some opportunities to link the human denial and acceptance of certain ideologically specific forms of consciousness to some of Fricker and Pohlhaus’ (among others) work on testimonial and hermeneutical injustice qua subjective credibility inflations and deficiencies . Especially with regard to certain Epistemically Unwarranted Beliefs. Very interesting, plenty to think on.

Isn’t the factor common to both access and phenomenal consciousness (in humans at least) the sense of an “I”? That there must be a subject for the content of either to make any sense, or to have any purpose.

Looking forward to your next post.

There is so much ado about consciousness and so little traction.

IMO the most succinct explanation you are ever going to get is as follows.

Rememberable awareness [“C”] is no more and no less than what it is like to be the timely updating of the model of self in the world [MSITW] which is maintained within your brain. This model is essential for navigation within your physical and social environments. By timely I mean that comparisons of before and after occur fast enough for you to keep abreast of everything important going on around you [and, occasionally, within you].

MSITW has three essential components:

1/ representations of currently significant parts or aspects of self,

2/ representations of currently significant parts or aspects of the world, and

3/ currently significant relationships between 1/ and 2/.

My acronym for this description is UMSITW [pronounced “um-see-two”] and I believe it is not contradicted by any clear and unambiguous empirical evidence that I have heard of. Furthermore I think it harmonises well with most of the insightful theories about consciousness I have seen put forward in books by neuroscientists.