Welcome to the Brains Blog’s Symposium series on the Cognitive Science of Philosophy. The aim of the series is to examine the use of diverse methods to generate philosophical insight. Each symposium is comprised of two parts. In the target post, a practitioner describes their use of the method under discussion and explains why they find it philosophically fruitful. A commentator then responds to the target post and discusses the strengths and limitations of the method.

In this symposium, Paul Conway (University of Portsmouth) argues that, although moral dilemmas do not tell us whether laypeople are deontologists or utilitarians, they can be used to study the psychological processes underlying moral judgment. Guy Kahane (University of Oxford) provides commentary, suggesting that the moral dilemmas we care about go far beyond trolley-style scenarios.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

What Do Moral Dilemmas Tell Us?

Paul Conway

Imagine you could kill a baby to save a village or inject people with a vaccine you know will harm a few people but save many more lives. Imagine a self-driving car could swerve to kill one pedestrian to prevent it from hitting several more. Suppose as a doctor in an overburdened healthcare system you can turn away a challenging patient to devote your limited time and resources to saving several others. These are examples of sacrificial dilemmas, cousins to the famous trolley dilemma where redirecting a trolley to kill one person will save five lives.

Philosophers, scientists, and the general public share a fascination with such dilemmas, as they feature not only in philosophical writing and scientific research, but also popular culture, including The Dark Knight, The Good Place, M*A*S*H*, and Sophie’s Choice. Thanos also contemplated a sacrificial dilemma–kill half the population to create a better world–and there are reams of humorous dilemma memes online. So, dilemmas have struck a chord within and beyond the academy.

Yet, questions arise as to what dilemmas actually tell us. Academic work on dilemmas originated with Philippa Foot (1967), who used dilemmas as thought experiment intuition pumps to argue for somewhat arcane phenomena (e.g., the doctrine of double effect, the argument that harm to save others is permissible as a side effect but not focal goal). However, subsequent theorists began interpreting sacrificial dilemmas in terms of utilitarian ethics focused on outcomes and deontological ethics focused on rights and duties. Sacrificing an individual violates most interpretations of (for example) Kant’s (1959/1785) categorical imperative by treating that person as a means to an end/without dignity. Yet, saving more people maximizes outcomes, in line with most interpretations of utilitarian or consequentialist ethics, as described by Bentham (1843), Mill (1998/1861), and Singer (1980), among others.

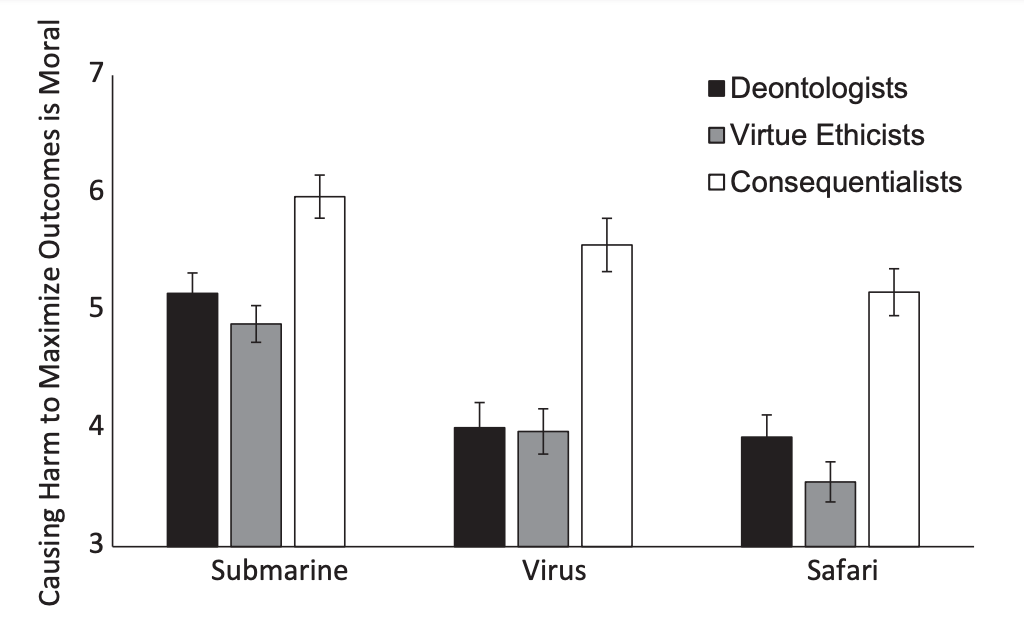

Some theorists have taken dilemma responses as a referendum on philosophical positions. On the surface, this may seem reasonable–after all, philosophers who identify as consequentialist tend to endorse sacrificial harm more often than those who identify as deontologists or virtue ethicists. For example, Fiery Cushman & Eric Schwitzgebel found this pattern when assessing philosophical leanings and dilemma responses of 273 participants holding an M.A. or Ph.D. in philosophy, published in Conway and colleagues (2018). Also, Nick Byrd found that endorsement of consequentialist (over deontological ethics) correlated with choosing to pull the switch on the trolley problem in two different studies that recruited philosophers (2022).

Figure 3: Philosophers who identify as consequentialist (similar to utilitarianism) endorse sacrificial harm more often than those identifying as deontologists or virtue ethicists (Conway et al., 2018).

If utilitarian philosophers endorse utilitarian sacrifice, then surely other people endorsing utilitarian sacrifice must endorse utilitarian philosophy, the reasoning goes. Presumably, people who reject sacrificial harm must endorse deontological philosophy. After all, some researchers argue people are reasonably consistent when making such judgments (e.g., Helzer et al., 2017).

However, this is a non sequitur. It assumes that philosophers and laypeople endorse judgments for the same reasons and that the only reasons to endorse or reject sacrificial harm reflect abstract philosophical principles. It also inappropriately reverses the inference: sacrificial judgments are utilitarian because they align with utilitarian philosophy; that does not mean that all judgments described as utilitarian reflect only adherence to that philosophy.

One need only take the most cursory glance at the psychological literature on decision-making to note that many decisions human beings make do not reflect abstract adherence to principles (e.g., Kahneman, 2011). Instead, decisions often reflect a complex combination of processes.

For an analogy, consider a person choosing between buying a house or renting an apartment. The decision they arrive at might reflect many factors, including calculations about size and cost and location of each option, but also intuitive feelings about how much they like each option—importantly, how much they like each option relative to one another (a point we will return to).

Sure, some people might consistently prefer houses and other consistently prefer apartments, but many people might start off living in an apartment and later on move to a house when their family grows. Does anyone think that such decisions reflect rigid adherence to an abstract principle such as ‘apartmentness’? Likewise, some famous people consistently live in houses (Martha Stewart?) and others in apartments (Seinfeld?)—does that mean that everyone choosing one or the other makes that choice for the same reason (e.g., they are the star of a hit TV show set in New York)? Moreover, a house is still a house no matter the reason someone selects it, just as a sacrificial decision that maximises outcomes is consistent with utilitarian philosophy even if someone chooses it for less than noble reasons.

The problems interpreting dilemmas deepened when researchers stared noting the robust tendency for antisocial personality traits, such as psychopathy, to predict acceptance of sacrificial harm (e.g., Bartels & Pizarro, 2011). Do such findings suggest that psychopaths genuinely care about the well-being of the most people, and may in fact be moral paragons? Or do such findings suggest that sacrificial dilemmas fail to measure the things philosophers care about after all (see Kahane et al., 2015)?

If dilemma responses should be treated as a referendum on adherence to abstract philosophical principles, then clearly the sacrificial dilemma paradigm is broken.

However, there is another way to conceptualize dilemma responses: from a psychological perspective. Returning to the point about the role of psychological mechanisms involved in decision-making, such as apartment hunting, one can ask the question, What psychological mechanisms give rise to acceptance or rejection of sacrificial harm?

Note this question shifts away from the question of endorsement of abstract philosophy and focuses instead on understanding judgments. In other words, instead of trying to understand abstract ‘apartmentness,’ researchers should ask, Why did this person select this apartment over that house?

This perspective was first popularized by a Science paper published by Greene and colleagues at the turn of the millennium. They gave dilemmas to participants in an fMRI scanner, and argued for a dual process model of dilemma decision-making: intuitive, emotional reactions to causing harm motivate decisions to reject sacrificial harm, whereas logical cognitive processing about outcomes motivate decisions to accept sacrificial harm (thereby maximizing outcomes).

Consistent with this argument, people higher in emotional processing, such as empathic concern, aversion to causing harm, and agreeableness, tend to reject sacrificial harm (e.g., Reynolds & Conway, 2018), whereas people higher in logical deliberation, such as cognitive reflection test performance, tend to accept sacrificial harm (e.g., Patil et al., 2021; Byrd & Conway, 2019). There is plenty more evidence, some of it a bit mixed, but overall, the picture from hundreds of studies roughly aligns with this basic cognitive-emotional distinction, though evidence suggests roles for other important processes as well.

Importantly, the dual process model suggests there is no one-to-one match between judgment and process. Instead, a given judgment people arrive at reflects the relative strength of these processes. Just as someone who typically might choose an apartment may get swayed by a particularly nice house, sacrificial judgments theoretically reflect the degree to which emotional aversion to harm competes with deliberation about outcomes. Increases or reductions of either process should have predictable impacts on sacrificial judgments.

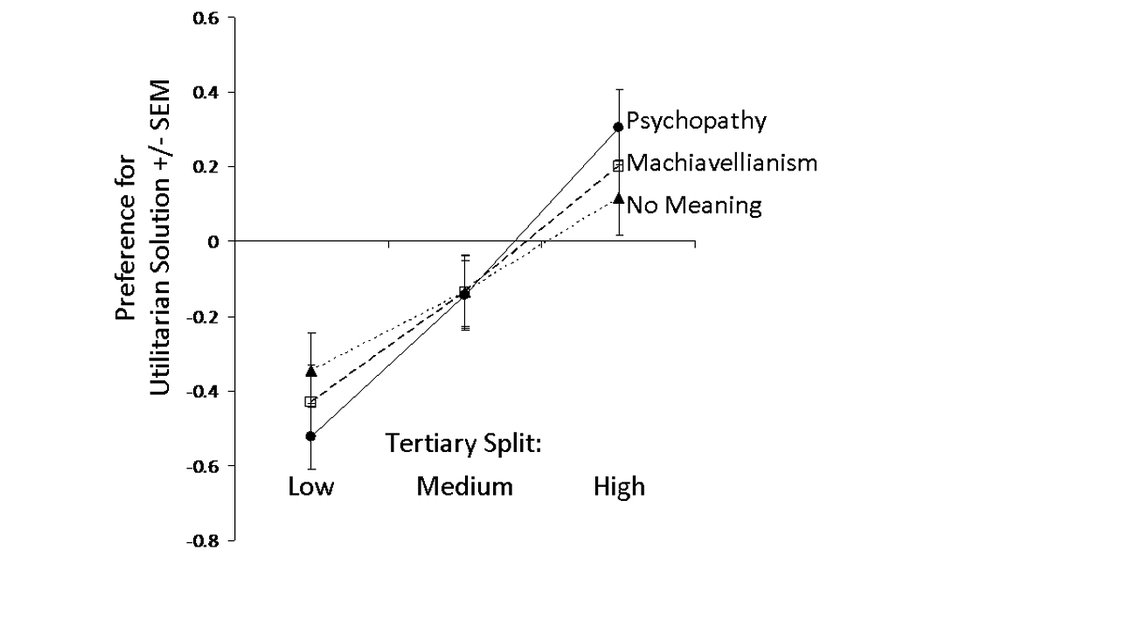

Therefore, it makes perfect sense why psychopathy and other antisocial personality traits should predict increased acceptance of sacrificial harm: such traits reflect reduced emotional concern for others’ suffering, a ‘callous disregard for others’ well-being.’ Hence, people high in such traits should feel low motivation to reject sacrificial harm—even if they do not necessarily feel particular concern for the greater good.

This argument is corroborated by modelling approaches, such as process dissociation (Conway & Gawronski, 2013) and the Consequences, Norms, Inaction (CNI) Model (Gawronski et al., 2017). Rather than examining responses to sacrificial dilemmas where causing harm always maximizes outcomes, these approaches systematically vary the outcomes of harm—sometimes harming people (arguably) fails to maximize outcomes.* Instead of examining strict decisions, these approaches analyse patterns of responding: some participants systematically reject sacrificial harm regardless of whether doing so maximizes outcomes (consistent with deontological ethics). Other participants consistently maximize outcomes, regardless of whether doing so requires causing harm (consistent with utilitarian ethics). Some participants simple refuse to take any action for any reason, regardless of harm or consequences (consistent with general inaction).

Studies measuring antisocial personality traits using modelling approaches show an interesting pattern. As predicted, psychopathy and other antisocial traits indeed predict reduced rejection of sacrificial harm (i.e., low deontological responding)—but they do not predict increased utilitarian responding—quite the opposite. Antisocial traits also predict reduced utilitarian responding (just to a lesser degree than reduced deontological responding, Conway et al., 2018; Luke & Gawronski, 2021).

In other words, people high in psychopathy leap at the opportunity to cause harm for the flimsiest reason that gives them plausible deniability—rather than demonstrating concern for utilitarian outcomes.

Meanwhile, people who care deeply about morality, such as those high in moral identity (caring about being a moral person, Aquino & Reed, 2002), deep moral conviction that harm is wrong (Skitka, 2010), and aversion to witnessing others suffer (Miller et, al., 2014) simultaneously score high in both aversion to sacrificial harm and concerns about outcomes—in other words, they seem to show a genuine dilemma: tension between deontological and utilitarian responding (Conway et al., 2018; Reynolds & Conway, 2018; Körner et al., 2020).

Importantly, most of these findings disappeared when looking at regular sacrificial judgments where causing harm always maximizes outcomes—such judgments force people to ultimately select one or the other option, losing the ability to test any tension between them. Some people might be extremely excited about both a house and apartment, yet ultimately have to choose just one—other people might be unenthusiastic about either choice, yet also must ultimately choose one. What matters is not so much the choice they make, but the complex psychology behind their choice. This is worth studying, even if it does not reflect some abstract principle.

Hence, it may be too soon to ‘throw the baby out with the bathwater’ and abandon dilemma research as meaningless or uninteresting. Dilemma judgments reflect a complex combination of psychological processes, few of which align with philosophical principles, but many of which are fascinating in their own right. Dilemmas, like other psychological decision-making research, provide a unique window into the psychological processes people use to resolve moral conflicts (Cushman & Greene, 2012). Dilemmas do not reflect adherence to philosophical principles—researchers have developed other ways to assess such things (Kahane et al., 2018)—but they remain important to study.

This is because unfortunately, whereas the trolley dilemma itself is purely hypothetical, sacrificial dilemmas occur in the real world all the time. When police use force in service of the public good, judges sentence dangerous offenders to protect victims, when parents discipline children to teach them valuable lessons, or professors fail students who have not completed work to preserve disciplinary standards and ensure qualifications–each of these situations parallels sacrificial dilemmas.** As decision-makers face many complex sacrificial scenarios in real life, which often reflect matters of life or death, it is vital to understand the psychology involved.

Think of an administrator of a hospital overwhelmed by COVID deciding who will be sacrificed to save others—do you want that person to be high in moral identity, struggling between two moral impulses, or high in psychopathy, largely indifferent either way? The psychological processes involved in dilemma decision-making are vital for society to study, regardless of any philosophical connotations they (don’t typically) have.

Notes

*The CNI model also manipulates whether action harms or saves a focal target.

**Assuming fair and judicious application of police force, assuming judges employ utilitarian rather than punitive approaches to sentencing, assuming parental discipline is well-meaning and well calibrated to teaching valuable lessons, etc. No doubt reality is more complex than this, but the general framework of dilemmas nonetheless permeates many important decisions.

_____________

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Commentary: Why Dilemmas? Which Dilemmas?

Guy Kahane

________

We sometimes face moral dilemmas: situations where it’s incredibly hard to know what’s the right thing to do. One reason why moral philosophers develop elaborate ethical theories like utilitarianism or deontology is in order to give us principled ways to deal with such difficult situations. When philosophers argue over which ethical theory or principle is right, they sometimes consider what their theories would tell us to do in various moral dilemmas. But they often also consider how these principles would apply in thought experiments: carefully designed hypothetical scenarios (which can be outlandish but needn’t be) that allow us to tease apart various possible moral factors. Thought experiments aren’t meant to be difficult—in fact, if we want to use them to test competing moral principles, the moral question posed by a thought experiment should be fairly easy to answer. What is hard—what requires philosophical work—is to identify moral principles that would make sense of our confident intuitions about various thought experiments and real-life cases.

The famous trolley cases were first introduced by Philippa Foot and Judith Jarvis Thomson as thought experiments, not as dilemmas. Foot found it obvious that we should switch a runaway train to a different track if this would lead to one dying instead of five. She was trying to shed light on what was a highly controversial moral issue in the 1960s (and, alas, remains controversial)—whether abortion is permissible—not in the ethics of sacrificing people in railway (or for that matter, military or medical) emergencies. The so-called trolley problem isn’t concerned with whether it’s alright to switch the runaway train or, in Thomson’s variant, to push someone off a footbridge to stop such a train from killing five (Thomson and most people think that’s clearly wrong), but to identify a plausible moral principle that would account for our divergent moral intuitions about these structurally similar cases.

Foot would have probably found it very surprising to hear that her fantastic scenario is now a (or even the) key way in which psychologists study moral decision-making. Her thought experiment about a runaway trolley has by now been used in countless ‘real’ experiments. For example, psychologists look at how people will respond to such scenarios where they are drunk, or sleep deprived, or have borderline personality disorder, or when these scenarios are presented in a hard to read font or when the people involved are family relatives or foreign tourists or even (in some studies I’ve been involved in) aren’t people at all but animals! A great deal of interesting data has been gathered in this way but, weirdly enough, it’s nevertheless not yet so clear what all of that can teach us, let alone why trolley scenarios are taken to be so central to the study of the psychology of moral decision-making.

There is one answer to this question that both I and Paul Conway reject. It goes like this. A central debate in moral philosophy is between utilitarians (who seek to maximise happiness) and deontologists (who believe in rules that forbid certain kind of acts). Utilitarians and deontologists give opposing replies to certain trolley scenarios: utilitarians will always sacrifice some to save the greater number while deontologists think some ways of saving more lives are wrong. So by asking ordinary people whether they would sacrifice one to save five we can find out the extent to which people follow utilitarian or deontological principles. But this is a poor rationale for doing all of those psychological experiments. To begin with, as Paul points out, the vast majority of people don’t really approach moral questions by applying anything resembling a theory. And although it’s true that utilitarians approach these dilemmas in a distinctive way, the trolley scenarios weren’t really devised to contrast utilitarianism and deontology, and are just one kind of (fairly peculiar) case where utilitarianism clashes with alternative theories (Kahane et al., 2015; Kahane, 2015; Kahane et al., 2018). For example, utilitarians also typically hold that we should ourselves make great sacrifices to prevent harm to distant strangers, wherever they may be (e.g. by donating most of our income to charities aiding people in need in developing countries), while deontological theories often see such sacrifices as at best optional. But, as Paul also agrees, willingness to push someone else off a footbridge tell us little or nothing about someone’s willingness to sacrifice their own income, or well-being, or even life, for the sake of others (Everett & Kahane, 2020).

A better answer, which Paul favours, is that by studying how ordinary people approach these scenarios, we can uncover the processes that underlie people moral decision-making. It’s precisely because people often don’t make moral decisions by applying explicit principles, and because what really drives such decisions is often unconscious, that studying them using psychological methods (or even functional neuroimaging) is so interesting. According to one influential theory, when people reject certain ways of sacrificing one to save a greater number (for example, by pushing them off a footbridge), these moral judgments are driven by emotion (Greene et al. 2004). When they endorse such sacrifice, this can be (as in the case of psychopaths) just because they lack negative emotional response most of us have to directly harming others, but it can also be because people engage their capacity for effortful reasoning. This is an intriguing theory that Paul has done much to support and develop (see e.g. Conway & Gawronski, 2013). As a theory of what goes in people’s brains when they response to trolley scenarios, it seems to me still incomplete. What, for example, are people doing exactly when they engage in effortful thinking and decide that it’s alright to sacrifice one for the greater good? We’ve already agreed they aren’t applying some explicit theory such as utilitarianism. Presumably they also don’t need a great effort to calculate that 5 is greater than 1—as if those who don’t endorse such sacrifices are arithmetically challenged! But if the cognitive effort is simply that needed to overcome a strong immediate intuition or emotion against some choice, this doesn’t tell us anything very surprising. Someone might similarly need to make such an effort in order, for example, to override their immediate motivation to help people in need and selfishly walk away from, say, the scene of a train wreck (Kahane, et al. 2012; Everett & Kahane, 2020).

Perhaps a more important question is what we really learn about human moral decision-making if, say, one kind of response to trolley scenarios is (let’s assume) based in emotion and another based in ‘reason’. There is one controversial answer to this further question that Paul doesn’t say much about. We earlier rejected the picture of ordinary people as lay moral philosophers who apply explicit theories to address dilemmas. But there’s something to be said for the reverse view: that moral philosophers are more similar to laypeople than they seem. Philosophers do have their theories and principles, but it might be argued that these ultimately have their source in psychological reactions of the sort shared with the folk. Kant may appeal to his Categorical Imperative to explain why it’s wrong to push a man off a footbridge, but perhaps the real reason he thinks this is wrong is that he feels a strong emotional aversion to this idea. And if ethical theories have their roots in such psychological reactions, perhaps we can evaluate these theories by comparing these roots. In particular, utilitarianism may seem to come off better if its psychological source is reasoning while opponent views are really built on an emotional foundation, or at least on immediate intuitions that are, at best, reliable only in narrow contexts (see e.g. Greene, 2013). This style of argument has generated a lot of debate. Here I’ll just point back to some things I already said. If when people who endorse sacrificial decisions ‘think harder’ they are just overcoming some strong intuition, this leaves it entirely open whether they should overcome it. More importantly, as we saw, trolley scenarios capture just one specific implication of utilitarianism (its permissive attitude to certain harmful ways of promoting the greater good). But it leaves it entirely open how, for example, people arrive at judgments about self-sacrifice or about concern for the plight of distant strangers. In fact, the evidence suggests that such judgments are driven by different psychological processes.

Paul offers another justification for focusing on trolley-style scenarios. We can forget about philosophers and their theories. The fact is that people actually regularly face moral dilemmas, and it’s important to understand the psychological processes in play when they try to solve them. This seems plausible enough. But although some psychologists (not Paul) sometimes use ‘moral dilemmas’ to just mean trolley-style scenario, there are very many kinds of moral dilemmas—and as we saw, some classical trolley scenarios aren’t even dilemmas, properly speaking! Should we keep a promise to a friend if this will harm a third party? Should we send our children to private schools that many other parents can’t afford? Should we go on that luxury cruise instead of donating all this money to charities that save lives? It’s doubtful (or at least needs to be shown) that the psychology behind peculiar trolley cases really tells us much about these very different moral situations. If we want to understand the psychological of moral dilemmas we need to cast a much wider net.*

I don’t think Paul wants to say that by studying trolley scenarios, we can understand moral dilemmas in general. He rather says that there is a category of moral dilemma that people in fact face in certain contexts—especially military and medical ones—which is well worth studying at the psychological level. This seems right, but if such cases don’t really tell us much about grand philosophical disputes, nor hold the key to the psychology of moral decision-making (as many psychologists seem to assume), or even just to the psychology of moral dilemmas, then do trolley really deserve this much attention? Why spend all that effort studying people’s responses to these farfetched situations rather than to the numerous other moral dilemmas people face? Moreover, even if we want to uncover the psychology of this kind of actual choice situation, why bring in runaway trains instead of cases that actually resemble such (pretty rare) real-life situations. Doctors sometimes need to make tragic choices but a doctor who actively killed a patient to save five others will simply be committing murder. Finally, while it will no doubt be interesting to discover the psychological processes and factors that shape decisions in real-life sacrificial choices, it would be good to know what exactly we are supposed to do with this knowledge. Will it, in particular, help us make better choices when we face such dilemmas? But this takes us right back to the tantalising gap between ‘is’ and ‘ought’, and to those pesky ethical theories we thought we’d left behind…

Notes

* See Nguyen et al. (2020) for a fascinating analysis of 100,000 moral dilemmas culled from the ‘Am I the Asshole’ subreddit—few of these are even remotely similar to trolley scenarios.

___

* * * * * * * * * * * *

References

___________

Aquino, K., & Reed, I. I. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 1423-1440.

Bartels, D. M., & Pizarro, D. A. (2011). The mismeasure of morals: Antisocial personality traits predict utilitarian responses to moral dilemmas. Cognition, 121, 154–161.

Bentham, J. (1843). The Works of Jeremy Bentham (Vol. 7). W. Tait.

Byrd, N. (2022). Great Minds do not Think Alike: Philosophers’ Views Predicted by Reflection, Education, Personality, and Other Demographic Differences. Review of Philosophy and Psychology.

Byrd, N., & Conway, P. (2019). Not all who ponder count costs: Arithmetic reflection predicts utilitarian tendencies, but logical reflection predicts both deontological and utilitarian tendencies. Cognition, 192, 103995.

Caviola, L., Kahane, G., Everett, J., Teperman, E., Savulescu, J., and Faber, N. (2021). Utilitarianism for animals, Kantianism for people? Harming animals and humans for the greater good. The Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 150(5), 1008-1039.

Conway, P., & Gawronski, B. (2013). Deontological and utilitarian inclinations in moral decision-making: a process dissociation approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 216-235.

Conway, P., Goldstein-Greenwood, J., Polacek, D., and Greene, J. D. (2018). Sacrificial utilitarian judgments do reflect concern for the greater good: Clarification via process dissociation and the judgments of philosophers. Cognition, 179, 241-265.

Cushman, F., & Greene, J. D. (2012). Finding faults: How moral dilemmas illuminate cognitive structure. Social neuroscience, 7(3), 269-279.

Everett, J. and Kahane, G. (2020). Switching tracks: A multi-dimensional model of utilitarian psychology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(2), 124-134.

Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect. Oxford Review, 5, 5–15.

Gawronski, B., Armstrong, J., Conway, P., Friesdorf, R., & Hütter, M. (2017). Consequences, norms, and generalized inaction in moral dilemmas: The CNI model of moral decision-making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113, 343-376.

Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron, 44, 389–400.

Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293, 2105–2108.

Greene, Joshua (2013). Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them. Penguin Press.

Helzer, E. G., Fleeson, W., Furr, R. M., Meindl, P., & Barranti, M. (2017). Once a utilitarian, consistently a utilitarian? Examining principledness in moral judgment via the robustness of individual differences. Journal of Personality, 85, 505-517.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Kant, I. (1959). Foundation of the metaphysics of morals (L. W. Beck, Trans.). Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill. (Original work published 1785)

Kahane, G., Wiech, K., Shackel, N., Farias, M., Savulescu J. and Tracey, I. (2012). The neural basis of intuitive and counterintuitive moral judgement. Social, Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7(4), 393- 402.

Kahane, G., Everett, J. A., Earp, B. D., Farias, M., & Savulescu, J. (2015). ‘Utilitarian’ judgments in sacrificial moral dilemmas do not reflect impartial concern for the greater good. Cognition, 134, 193-209.

Kahane, G. (2015). Side-tracked by trolleys: Why sacrificial moral Dilemmas tell us little (or nothing) about utilitarian judgment. Social Neuroscience, 10(5), 551-560.

Kahane, G., Everett, J. A., Earp, B. D., Caviola, L., Faber, N. S., Crockett, M. J., & Savulescu, J. (2018). Beyond sacrificial harm: A two-dimensional model of utilitarian psychology. Psychological Review, 125(2), 131.

Körner, A., Deutsch, R., & Gawronski, B. (2020). Using the CNI model to investigate individual differences in moral dilemma judgments. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(9), 1392-1407.

Luke, D. M., & Gawronski, B. (2021). Psychopathy and moral dilemma judgments: A CNI model analysis of personal and perceived societal standards. Social Cognition, 39, 41-58.

Mill, J. S. (1998). Utilitarianism (R. Crisp, Ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1861)

Miller, R. M., Hannikainen, I. A., & Cushman, F. A. (2014). Bad actions or bad outcomes? Differentiating affective contributions to the moral condemnation of harm. Emotion, 14(3), 573.

Nguyen, T. D., Lyall, G., Tran, A., Shin. M., Carroll, N. G., Klein, C., Xie, L. (2022). Mapping topics in 100,000 real-life moral dilemmas. ArXiv preprint arXiv:2203.16762

Patil, I., Zucchelli, M. M., Kool, W., Campbell, S., Fornasier, F., Calò, M., … & Cushman, F. (2021). Reasoning supports utilitarian resolutions to moral dilemmas across diverse measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(2), 443.

Reynolds, C. J., & Conway, P. (2018). Not just bad actions: Affective concern for bad outcomes contributes to moral condemnation of harm in moral dilemmas. Emotion.

Singer, P. (1980). Utilitarianism and vegetarianism. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 325-337.

Skitka, L. J. (2010). The psychology of moral conviction. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(4), 267-281.

Two surprising outcomes of this discussion:

Also, the visualizations of the correlations between endorsing utilitarianism (over deontology) and pulling the switch on the trolley problem from Byrd (2022) can be found in this PNG file.

Thanks for these thoughts, Nick. I agree I was pleased to see more agreement than expected. I think you are right that dilemma responses can be meaningful and interesting. I just think that any given response to a given dilemma is often uninformative or even misleading about what processes a person used to arrive at that judgment or whether they adhere to some grander belief system. I think to get at that we need to assess responses across an array of dilemmas and use theory and evidence and social cognitive approaches to test what kinds of psychological experiences give rise to what kind of judgments in what kind of situations. Hence, by all means consider dilemma responses but do so with caution and informed by theory and evidence. Nick, I feel confident you do, but I do not always see that same level of careful thinking.

I also, if I may, wanted to briefly address two points Guy made. These are good points and worth discussing in my view.

Is dilemma research more common than it ought to be?

Guy suggested that the field of moral psychology is somehow dominated by dilemma research, and I suggest that is not really true given broader look. For example, when I teach my undergraduate moral psychology class I dedicate only two lectures of twenty five to dilemmas, spending the rest of the time talking about moral development, moral foundations theory, dyadic morality, prosocial behavior, evolutionary models, models of moral emotions, blame, forgiveness, empathy, intergroup conflict, etc. A brief look at any social psychology textbook with invariably reveal a chapter on aggression and another on prosocial behavior—and dilemmas are rarely if ever mentioned. A quick google search of ‘prosocial behavior’ reveals more hits than a search for ‘moral dilemma’ and I would guess that a majority of dilemma hits pertain to philosophy rather than psychology. Dilemmas got a lot of popular press for a while and managed to get philosophy and psychology in conversation more so than other areas, giving them what seems like outsized influence, but I suggest that in a broader history of scientific study of morality they form only one modest subset of active research.

Furthermore, I suggest that dilemma research is useful because dilemma decisions can reflect highly important cases where harm and suffering are going to occur. Arguably, every military decision in history matches the template of a sacrificial dilemma, including current world tensions and nuclear deterrence. Arguably, every police force and justice system actively engages in sacrificial dilemma decision-making with every arrest and every sentence. Every teacher or parent or other caregiver in charge of disciplinary action faces sacrificial dilemmas, as does every institutional disciplinary body and organizational leader. There are countless decisions that entail harming or disciplining or taking resources from some group to achieve some broader goal. These are not small or inconsequential decisions—these are omnipresent and life shaping. Therefore, I suggest that research into the psychological mechanisms involved matter and are worth studying alongside prosocial motivations and moral foundations and moral emotions and all the myriad other topics that scientists

The role of affect and cognition in moral decision-making

Guy is correct that I did not spend a lot of time talking about the role of affective and cognitive mechanisms involved in moral decision making, so perhaps I can add a little on this point. My current thinking is that the traditional ‘hard’ dual process model focused on reaction times and ‘intuition, has been debunked, but there remains plenty of evidence for a ‘softer’ dual process model that posits affective reactions to harm and cognitive evaluation of outcomes as two of several important mechanisms. A proper model may contain dozens of mechanisms, certainly far more than just two, but that does not mean these two that have been identified play no role. To clarify the argument, here is a brief excerpt from an upcoming paper:

Revised ‘soft’ dual-process model. Although there is little evidence for the hard dual process model, there remains considerable support for a ‘softer’ version that moves away from temporal claims. This version suggests that suggests that when people contemplate harmful actions that maximize outcomes, they experience an emotional, affect-laden aversion to the thought of harming another person, coupled with logical deliberation regarding overall outcomes. These two processes vie to influence the decision people reach, but operate largely in parallel, with the ultimate choice to accept or reject sacrificial harm reflecting the relatively stronger process winning out against the weaker.

Theoretically, each process can vary independently, and some factors may increase both—a point we will return to. For example, people high in emotional sensitivity to harm, such as empathic concern (Gleichgerrcht & Young, 2013) or aversion to causing harm (Miller et al., 2014), tend to reject sacrificial harm more often. Likewise, manipulations that amp up emotionality likewise increase rejection of sacrificial harm, such as by describing harm vividly (Bartels, 2008), or making harm close and personal (Greene et al., 2009). Moreover, people low in emotional sensitivity to harm, including those high in antisocial dark personality traits such as psychopathy, are more willing to accept sacrificial harm (e.g., Bartels & Pizarro, 2011), as are people whose concerns have been dulled, whether through drinking (Duke & Bègue, 2015) or emotional reappraisal (Lee & Gino, 2015). This point is often misinterpreted as ‘increased utilitarianism’ among such antisocial people (e.g., Kahane et al., 2015), but this interpretation is clarified by the modelling approaches discussed below. Antisocial personality traits appear to largely reflect differing degrees of emotional concerns about causing harm (i.e., reduced deontological judgments), rather than utilitarian considerations (Conway et al., 2018).

Independent of emotional concern about outcomes, decisions can also reflect individual differences and situational manipulations promoting careful logical deliberation about outcomes. For example, consider the Cognitive Reflection Test (Frederick, 2005). This test asks participants to solve tricky math questions such as A bat and a ball together cost $1.00. The bat costs $1.00 more than the ball. How much does the ball cost? Answer: 5 cents. Performance on this test predicts a wide variety of reasoning measures, and also the tendency to accept sacrificial harm to maximize outcomes (e.g., Paxton et al., 2012; Patil et al., 2020). Similar findings hold for measures of need for cognition, working memory capacity, and deliberative thinking (e.g., Conway & Gawronski, 2013; Bartels, 2008; Moore et al., 2008; cf. Körner et al., 2020), and extend to related moral decision-making (Jaquet & Cova, 2021). Likewise, making dilemmas ‘easier’ to deliberate about, such as increasing the ratio of lives gained to 1,000,000:1, increases acceptance of sacrificial harm (Trémolière & Bonnefon, 2014). Finally, some studies suggest that facilitating analytical thinking can increase acceptance of sacrificial harm (Li et al., 2018), although results on this point are somewhat mixed. Gawronski and colleagues (2017) argued that such findings reflect less hesitation to act rather than concern with outcomes per se, and other papers suggest cases where cognitive deliberation can increase harm rejection or reduce outcome-maximization responding as well (e.g., Körner & Volk, 2014; McPhetres et al., 2018; Rosas & Aguilar-Pardo, 2020). Individual difference findings tend to replicate robustly across labs, but manipulations of cognitive load or reaction time do not replicate as robustly, suggesting need of further research.

Overall, such findings, together with fMRI work linking acceptance and rejection of sacrificial harm to neural activation in cognitive and affective areas, respectively (e.g., Greene et al., 2004; Crockett, 2013; Cushman, 2013), as well as modelling work discussed below, lend considerable support to the soft version of the dual process model. It seems plausible that affective reactions to harm and cognitive evaluations of outcomes are indeed two processes that jointly contribute to dilemma judgments. That said, many findings also challenge the simplicity of the dual process model. For example, some studies find evidence of cognitive processing contributing to harm-rejection judgments (e.g., Rosas et al., 2019; McPhetres et al., 2018) and others find evidence of emotional concern for others contributing to outcome-maximizing judgments (e.g., Reynolds & Conway, 2018). Moreover, researchers have provided evidence for the influence of a wide array of other processes, including general inaction (Gawronski, et al., 2017), prevention mindsets (Gamez-Djokic & Molden, 2017), a focus on rules (e.g., Piazza & Landy, 2013), and self-presentation (Rom & Conway, 2018). Clearly, even the soft dual process model is not sufficient to describe all factors contributing to dilemma judgments. Nonetheless, this model appears not so much incorrect as incomplete: affective reactions to causing harm and cognitive evaluations appear to be two of many processes that can influence dilemma responding (Conway et al., 2018). Therefore, researchers should not equate dilemma responses with processes, but neither should they dismiss the dual process model as irrelevant. Moral judgment is multi-faceted and complex; demonstrating the influence of one process does not rule out the influence of others.

Moral dilemmas go way back. As does philosophy. And, religion. Also, science, though newer. Cognitive science, in a better, if not perfect, world could tell us more. I wonder where the dilemma lies. Insofar as we create and alter reality, For want of a better term, I have offered contextual reality. Or, contextualism. One foundation for this, I contend, is: circumstances shift as contingencies surface. Long before the internet and social media, contextualism was in the picture.

In the ancient realm of an antipathy among philosophy, religion and a science, religion held an upper hand. Philosophy held an initial influence—thinkers were free to do that. Religion challenged this, claiming men should not trust their own minds—should trust some higher authority. Why, men asked. On faith. the sages replied. Or, because it is written. Science, wishing freedom to pursue knowledge, tried to remain calmly detached. Circumstances and contingencies morphed. I have claimed this before. Some have thought about it. My notion about contextualism springs from origins. Or, history, if you prefer. We have been there before. We are there, every day.