In the last post we took physical systems (organisms, brains, solar systems) that contained each other as parts, and asked which were conscious. But some philosophers think this is misguided from the get-go: no physical system, whatever its features, can strictly be a subject of consciousness, but can only ‘support’ or ‘constitute’ a subject. Psychological theorists of personal identity, for instance (e.g. Lewis 1976, Parfit 1984, Noonan 1989, Rovane 1998), standardly say that human organisms (something with biological persistence conditions) are distinct from, but constitute, human persons (something with psychological persistence conditions). So if we reconfigured someone else’s brain to have your exact personality and memories, that would be you (the same person) but now constituted by a different organism.

On this sort of view, the whole idea of a subject’s ‘parts’ has to be re-thought, because we can’t pick out those parts in non-mental terms (e.g. as the organs and tissues of an organism). Subjects are individuated by the relations among sets of mental events: for instance, psychological theorists will tend to say that any future stream of consciousness that contains first-person memories of my present experiences is my consciousness, whatever brain it’s in. So the natural way to think of ‘parts’ of a subject is to focus on those sets of experiences, and the subsets within them.

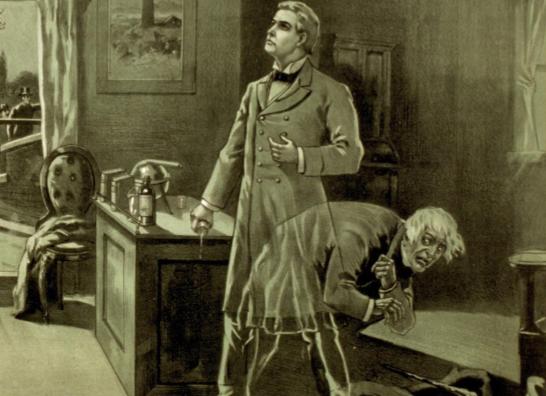

Consider, for example, the fictitious case of Jekyll and Hyde, two personalities ‘sharing a body’. (Actual cases of what is called ‘Dissociative Identity Disorder’ are much more complicated and ambiguous, which is why it’s easier and safer to work with a simplified, dramatised, sort of example.) More precisely, suppose they don’t alternate but co-exist (cf. Olson 2003, pp.341-342):

“When we ask that body for a name, we sometimes get an answer like “Dr. Jek- no, Hyde! – no, let me speak – it’s Hyde, yes, definitely – agh! – oh alright, go on then – Dr. Jekyll, pleased to meet you.” When we give it an opportunity for trouble-making, we observe a few moments of spasms and contortions, as though some sort of struggle is going on, followed by either refusal or embrace of the opportunity, perhaps with one arm trying to interfere with what the rest of the body is doing. At other times we might find the body behaving calmly, striking a middle course between respectability and vice, and speaking in the following odd way: “Hello. This is Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, both pleased to meet you and at your disposal.” If pressed, the body explains that ‘they’ have come to a cooperative arrangement, though temptations sometimes prompt a return to squabbling and contests over control of limbs.” (Combining Minds, page 233)

I think there’s a natural sense in which these are two people, two subjects. But they need not be based in different parts of the brain – what differentiates them is the lack of various sorts of unification among their mental states. But exactly what sort of unity is lacking might be complicated, and comes in any number of degrees:

“…consider [a version where] the two have no secrets from each other, even in their most private thoughts. When Hyde indulges in a fantasy of cruel mayhem, Jekyll must experience every grisly detail, and if Jekyll realises that a vulnerable person is undefended in the next room, Hyde immediately and gleefully jumps into action on this belief. Judged by the standards of access-unity, their experiences are highly unified; judged by the standards of [consistency in desires], they are highly disunified… …Or suppose that their phenomenology involves a single field of perceptual and bodily sensations, with distinct sets of urges, feelings, and plans focused on particular parts of them. When we prick the body’s finger, a single experience of localised bodily pain is the focus both of Hyde’s outrage and desire for vengeance, and for Jekyll’s perturbed contemplation of possible reasons we might have pricked him…” (Combining Minds, pages 239-240)

Here standard versions of the psychological theory have an awkward choice: either Jekyll and Hyde are the same person (because despite all their disunities, their mental states are nevertheless unified enough to constitute a single subject), or they are two distinct people (because despite all their unity, their mental states are not unified enough to constitute a single subject – though all of Hyde’s states are, and all of Jekyll’s states are). One problem is that either option seems to ignore something important about the scenario; another problem is that we can always adjust the scenario to make them a little more or a little less unified, and it looks like there must be some range of cases where it would be equally reasonable to set the unity threshold a little higher (so there are two people) or a little lower (so there’s only one).

The theory I call ‘psychological combinationism’ offers a way to recognise the full structure of the situation, both its unities and its disunities. It says that when a set of mental states is unified enough to constitute a subject (by some, perhaps quite low, standard), but subsets of those mental states are more unified (meeting a higher standard), we should think of the latter as constituting component subjects within the composite subject. In the example, the single subject we might call ‘Jekyll-Hyde’ is less psychologically unified than either of its two parts, ‘Jekyll’ and ‘Hyde’, but all three can nevertheless be recognised as conscious subjects.

What that recognition implies practically is a further question – whether, for instance, we should continue to take one-person-per-body as our ideal, and aim to unify different component subjects, or treat multiplicity as a normal form of variation, as advocated by self-described multiples here. I don’t think I’m qualified to pronounce on that.

With this framework in mind, we can also think about more everyday cases of inner conflict, where we ordinarily would use language about ‘struggling against oneself’, or of ‘two sides of me at war’. What is characteristically going on in such cases is not simply that we have desires with sharply opposed content, but that these desires seem to resist the normal process of decision-making, where we consider all our relevant desires, make a decision in light of them, and then follow it. Rather like political parties who refuse to abide by a parliamentary decision, some of our mental states just won’t submit to this important sort of mental unification. Psychological combinationism allows us to recognise that this differs only in degree from the extreme cases like Jekyll and Hyde: the psychic whole that usually identify ourselves with is less unified than it normally is, whereas (sometimes) two (or more) clusters within it show a greater degree of unity. Even though most of the time it may not be practically worthwhile to think of these subclusters as subjects (indeed, it might be harmful if it exacerbates the lack of overall unity), from a philosophical perspective we can still recognise that all three entities really exist, and all meet the criteria for being conscious subjects, considered in isolation.

(For what it’s worth, I think this is something like how we make sense of sub-ordinate and super-ordinate social groups: the members of one community have enough social interaction with the broader society that we can count them as members of that big society, but have stronger connections with a subset of people, forming a society within a society.)

Here is a very important thing to note, though: these patterns within our psyche are not the same type of thing as, and may not line up in any neat way with, the mechanical components of our underlying neural machinery. If some components of that machinery are themselves conscious, then we cannot assume that our conscious parts as described by functionalist combinationism will match up with our conscious parts as described by psychological combinationism.

That is, our subjectivity may be not only composite, but doubly composite, in two completely different ways. To use the terms I employ in Combining Minds, the underlying substrate is composite, and the ‘persona’ it consitutes is composite, and both substrates and personas have some claim to be the things we normally refer to as ‘subjects of experience’, as ‘us’.

For this reason, we should be careful with pictures that conflate the two together, and one such picture is analogies between the mind and a society (rather like the reference to intransigent political parties mentioned above). Although social analogies have a very long pedigree as ways of thinking about the divided nature of our minds (going back at least to Plato, e.g. 1997, 2003), they are potentially misleading because social groups have a highly salient division into parts (human beings) which are generally both separate physical substrates (brains encased in bone) and also separate unified personas (consistent, integrated, personalities). But it doesn’t seem as though the brain in like this. The boundaries of our ‘component personas’ are malleable in a way that the boundaries of members of society are not – they are more like political parties, movements, or subcultures than like human individuals.

Ironically, this double-compositeness is part of what makes me cautious about claiming straightforwardly that ‘we have conscious parts’ – such a statement would most naturally suggest that we have the sort of parts which have both distinct substrates and distinct personas. But the reason for caution about these simple claims of compositeness is not that we are really more unified than that, but that we are more multiply composite than we are used to thinking about.

References:

Lewis, D. (1976). “Survival and Identity.” in The Identities of Persons, A. Rorty (ed.), University of California Press: 17-40.

Olson, E. (2003). “An Argument for Animalism.” In Personal Identity, R. Martin and J. Barresi (eds.), Blackwell: 318-335.

Noonan, H. (1989). Personal Identity. Routledge

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons.Oxford University Press

Plato (1997). “Phaedrus”, A. Nehamas and P. Woodruff (trans.), in Plato: Complete Works, ed. John M. Cooper, Hackett.

Plato (2000). “The Republic”, T. Griffith (trans.), G. R. F. Ferrari (ed.), Cambridge University Press.

Rovane, C. (1998). The Bounds of Agency: An Essay in Revisionary Metaphysics. Princeton University Press