The goal of the post-Gettier Analysis of Knowledge program was to come up with a good X to plug into the formula “Knowledge = True Belief + X”, where X itself didn’t illicitly smuggle in the concept of knowledge (theories invoking “competence”, I’m looking at you). As the Analysis of Knowledge train rolled forward, philosophers swiftly found intuitive counterexamples to all the easy and natural-sounding X’s. The research program then split into two tracks, with some philosophers proposing exquisitely complicated X‘s to take care of counterexamples, and others proposing analyses of knowledge that were frankly counterintuitive in various ways. Neither track seemed able to find an analysis of knowledge that could win majority support.Meanwhile, it started to look hard to see why we’d intuitively attribute knowledge so much, if knowledge was such a delicate and convoluted condition, or if it was something ultimately quite counter-intuitive .

A fresh proposal emerged at the end of the last millennium, from the knowledge-first program, led by Tim Williamson. Maybe the tortured Analysis of Knowledge program wasn’t revealing a problem with knowledge, but rather a problem with itself. Perhaps there was something wrong with the question, “What non-epistemic X do you have to add to true belief in order to get knowledge?” As any fan of grue and bleen can tell you, simple concepts can appear to be definable only in really complex ways, if you restrict yourself to the wrong basic vocabulary when you set out to construct your definition. If we had assumed that believing was a more basic condition, and knowing some kind of elaboration on it, maybe that was a bad move.

The knowledge-first program starts with the idea that knowing is a basic mental state, and not a composite of believing plus other external non-mental factors. It’s true that knowing entails believing, but not because all knowledge starts out as belief, to which other non-mental factors get added. Knowing is more basic than believing, according to Williamson, and indeed, “Knowledge sets the standard of appropriateness for belief”, he says (2000, 47), so that “believing p is, roughly, treating p as if one knew p.” Knowing is a special kind of mental state: it is factive, or restricted to true propositions, where nonfactive states like believing can link a subject to truths or falsehoods. There are other factive mental states — you can only see that p, or be aware that p, if p is true — but knowledge is distinguished as the most general, the one entailed by all the others. If Smith sees that the ball is in the basket, Smith knows that the ball is in the basket (but not conversely: Smith could know that the ball is in the basket without seeing it there, for example if he is touching it, blindfolded).

The idea that knowledge could be a mental state drew many complaints from philosophers accustomed to thinking of knowledge as belief plus other factors. By contrast, psychologists working on mental state attribution routinely list knowledge as one of the paradigmatic mental states (alongside wanting and believing), and seem warmer to the idea that knowledge is more basic, or at least easier to attribute. Comparative psychologists, for example, will argue that chimpanzees can attribute knowledge but not belief. Developmental psychologists observe children across cultures speaking of knowledge before belief, and acquiring the meanings of those terms in that clear order (Tardif and Wellman 2000, p.35).

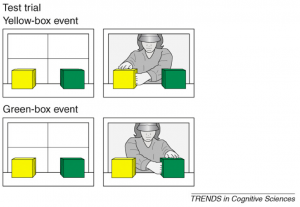

I went to bat for the other team and argued that the psychologists had this one right: knowledge is more basic, in part because the domain of what is known is simpler (reality!) where what is believed is much less constrained (anything real or unreal that anyone could take to be the case). That extra degree of freedom in believing makes it a more complex state, and more of a pain to represent. One of the things I talked about there was the well-established difficulty children have in explicit false belief attribution. A typical three-year-old child will fail the unexpected transfer task, for example: when Smith starts out knowing that the ball is in the basket, but the ball is then moved to the box behind Smith’s back, four and five-year olds will properly describe Smith as having a false belief, but younger children will systematically over-ascribe knowledge, when asked explicitly about Smith’s state of mind. It seems to take some extra work to describe the different state of affairs that out-of-touch Smith is stuck in, and it takes some extra developmental time to learn to attribute this state of mind explicitly (tasks just inviting a distinction between knowledge and ignorance are mastered substantially earlier than those asking for false belief attribution). Looking at this work, and at comparative work showing non-human primates able to track knowledge but not belief, I argued that our grip on belief requires prior mastery of knowledge (knowledge first, literally!).

That paper hit resistance from people like Stephen Butterfill, who is happy to see knowledge as a mental state, but reluctant to accept the priority claim, and from people like Aidan McGlynn, who doesn’t like the mental state thing either. Reasonably enough, they’ve called attention to recent work on younger children showing that they have some implicit ability to anticipate actions based on false beliefs, even when they can’t answer explicit questions correctly (for whatever reason, and there are interesting theories out there about the reasons).

It had been known for a while that three-year-old children will look at the correct spot — the empty basket — when anticipating what Smith will first do, searching for the ball, even when they explicitly answer that he will search elsewhere. Roughly ten years ago a wave of research began pushing the onset of “implicit false belief attribution” back earlier: Kristine Onishi and Renée Baillargeon found that 15-month-olds seem to anticipate behavior in accordance with false belief (looking longer, as if surprised, at situations in which Smith reaches in the right spot after an unwitnessed transfer). Ágnes Kovács has found reactions consistent with false belief tracking even in 7-month-old infants, suggesting that belief might be much easier to represent than we had thought, perhaps built into our innate social sense alongside concepts like wanting and knowing, as an equal partner from the start.

In my earlier paper on this stuff I’d mentioned but avoided discussion of the early infant work: I feared that any entanglement with it was going to add 20 pages and end inconclusively. It also didn’t seem deadly to the knowledge-first project — even Baillargeon and colleagues attributed the capacity to attribute “reality-congruent” states of mind to a system that had to develop prior to the capacity to attribute false belief.

But it was complicated, not least because there’s a lot that’s contested: Celia Heyes has argued that many key results can be explained by low-level perceptual novelty, and Ted Ruffman has argued that domain-general statistical learning will do the trick, coupled with natural infant biases to attend to human faces and behavior. Both of them have drawn attention to the danger of unwittingly taking our mature adult parsing of a scene for granted when we are observing how babies respond to it. For us it is natural and effortless to see Smith’s scenario as involving an agent who sees something, then fails to witness something, then comes back and reaches for something he wants; when we are asking whether the infant detects states of mind, we can’t just assume that their glimpse of an unwitnessed transfer already registers for them as a fact that this transfer was unwitnessed by that agent. For us, mental state explanations are so easy that it is hard for us to see behavior consistent with mental state explanation except as behavior driven by mental states: it takes effort to keep in mind that babies may not be in that position yet.

But even if mental state concepts are innate, babies aren’t born knowing that Smith wants the ball or knows that it is now in the basket: Ruffman in particular has emphasized that attributing particular attitudes (with their contents) to particular agents is a really non-trivial task (the difficulty of which is obscured for us as adults by our automatic registration of such things). Even if you think that infants are born with an innate sense of both knowledge and belief, they still need to learn who knows and believes what, under various conditions of presence, absence and occlusion. Whether mental state concepts are learned or innate, could it still be the case that belief attribution is parasitic on knowlege attribution?

I’ve been looking at the early infant work with that question in mind. In the standard belief recognition tasks used with prelinguistic infants, the behavior witnessed by the infant is compatible with any number of false beliefs, but there’s a very particular false belief that the researcher takes the infant to be (reasonably!) attributing to the agent, like the belief that the ball is still where the agent saw it last. In the unexpected transfer task, that belief is always something that started out with the status of knowledge (Smith originally knew the ball was in the basket, seeing it there). In unexpected contents tasks (watching an agent who sees a candy box that actually contains pencils) it makes sense to see the agent as thinking that the box contains candy only if you take the agent to see the candy box, and to have background knowledge about its typical contents. In misinformation tasks you see the agent as knowing what has been said. In all cases the attributor takes the agent to know something interestingly related to the belief that gets attributed. Even philosophers like Peter Carruthers who subscribe to one-system accounts with innate primitives (including “thinks”) don’t describe infants as encoding “thinks” directly upon witnessing an agent: as Carruthers narrates it, the infant first encodes an episode of seeing or being aware.

Muddying the waters: not everyone describes those first moments as moments of knowing, seeing or being aware that something is the case. Many new wave developmentalists label their contrasting scenarios (e.g. with and without the unseen transfer) not as scenarios in which there is knowledge/awareness versus false belief, but as scenarios involving mere true and false belief. The kind of state witnessed is the same across the board (belief!); what changes is only whether it does or doesn’t match reality. Actually, they are a bit casual about the labels (at least when judged from the perspective of an epistemologist who is maniacally concerned about the difference between knowledge and true belief). Here’s a standard line (from a recent review): “True-belief scenarios served as control conditions and differed from false-belief scenarios in that the protagonist knew at the end of the trial sequence where the object was located” (emphasis added). So wait, if you as a researcher pulled out the concept “knows” in describing what the infant saw, let’s not assume from the start that the infant witnessed the scene as true belief, maybe they saw it as something stronger, as knowledge.

Who even cares if the infant is seeing knowledge or true belief? What exactly is the difference, anyway? This was a point that my last post said I would get to, and I promise you I will get you there, turning to linguistics for help, but this post is getting much too long already, so, see you tomorrow for the next installment in my ongoing drama, “An Epistemologist Visits Other Disciplines.”