My last post focused on the relationship between minimal phenomenal selfhood in dreams, spatiotemporal self-location, and bodily experience. But there is another and in some ways more traditional way of thinking about the relationship between dreaming and the self. This is to focus on the epistemic relation between the self, both in dreams and after awakening, and the dream world.

On the one hand, there is a long tradition of regarding dreams and their interpretation as a vehicle towards genuine insight—about the future as in the prophetic dreams of the ancients, about the state of the physical body, as in diagnostic dreams thought to be indicative of illness, or about the psychological state of the dreamer, as in psychoanalytic dream theory. Quite often, these different views on the meaning of dreams are also associated with different theories on the sources of dreaming (Windt 2015b). Dreams have long been thought to provide access, in some way or another, to kinds of knowledge that are unavailable to us in wakefulness; they are thought to be unique sources of creativity and problem-solving, but also, occasionally, to unlock long-forgotten memories. Some version of this idea likely underlies the continued popular interest in dreams and dream interpretation (for a recent discussion and empirical investigation of the relationship between dreams, dream interpretation and insight, see Edwards et al. 2013).

On the other hand, dreaming has frequently been viewed as an obstacle towards knowledge and rational thought. Dreams have been described as the source of superstitious beliefs, as akin to madness and wake-state delusions (for a recent discussion of feelings of familiarity in dreams and wake-state delusions, see Gerrans 2013). The most famous philosophical example of this way of thinking about dreams is Descartes’ skeptical dream argument in the Meditations. There, he tells us that unless we can rule out that we are now dreaming, we cannot trust any of our sensory-based beliefs about the external world.

In contemporary dream research and empirically informed philosophical work, dreams are often described as a state of cognitive deficiency (Hobson et al. 2000; Metzinger 2003). In this view, our failure to realize, while we are dreaming, that we are dreaming results from an absence of rational thinking; to the extent that we think about the events and situations we are confronted with in our dreams at all, our reasoning has an illogical, associative, and ad hoc character. For this reason, it has even been suggested that dreams might be a research model of psychotic wake states (Hobson 1999; Gottesmann 2006, 2007; see Windt & Noreika 2011 for critical discussion). A key idea is that in nonlucid dreams, the dream self cannot be meaningfully described as a cognitive agent. It is only in lucid dreams, when we realize that we are dreaming, that wake-like cognitive agency becomes restored.

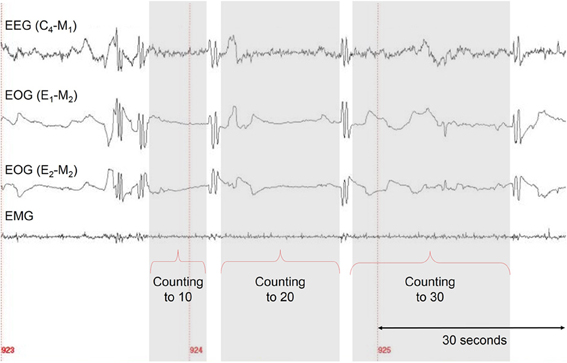

The investigation of lucid dreams, or dreams in which one realizes that one is now dreaming and often has some level of dream control, has now turned into a rigorous field of research in its own right. The view that dreams are necessarily and inherently deceptive—that the sudden insight that one is now dreaming terminates the dream and leads to awakening (see Sartre’s 1940 discussion of dreaming for an example)—has now been disproven. In the late 1970s, two independent research groups made use of an ingenious experiment (Hearne 1978, LaBerge 1985, 1988). Hypothesizing that there is a correlation between gaze shifts performed in the dream and the eye movements observed in the sleeping subject (the so-called “scanning hypothesis”), researchers asked experienced lucid dreamers sleeping in the laboratory to signal that they had now become lucid, for instance by looking right-left-right-left. These prearranged patterns of eye movements showed up on the electrooculogram, and the retrospective reports confirmed that the dreamers were actually lucid; in this way it was possible to prove that lucid dreams are a robust phenomenon and actually take place during sleep. This paradigm of signal-verified lucid dreaming has been used in numerous exciting studies, for instance for investigating changes in brain activity associated with the onset of lucidity (Voss et al. 2009), but also with specific actions performed during lucid dreams (such as fist clenching, the beginning and end of which is again marked with eye movement signals; Dresler et al. 2011), as well as for investigating the duration of dream actions and comparing them to their waking counterparts (Erlacher et al. 2013; see the figure at the bottom of this post). Researchers have even begun to use electrical stimulation over prefrontal areas to induce self-reflection and lucidity in dreams (Voss et al. 2014; see Voss & Hobson 2015 for an excellent review).

Conceptually, this work is interesting because it sheds light on the relationship between the cognitive processes underlying the formation of dream imagery and consciously experienced thought. It also suggests that in dreams, phenomenal selfhood varies by degrees. The onset of dream lucidity is accompanied by a change in self-related processing: as we begin to think about our ongoing experiences, we also gain metacognitive insight into the nature of our current conscious state and become lucid (Windt & Metzinger 2007). Importantly, in lucid dreams, metacognitive insight does not disrupt the ongoing dream, but can exist alongside vivid and often bizarre dream imagery. This is another reason for saying that the sense in which we feel present in our dreams cannot be reduced to cognitive immersion, comparable to the way in which we might temporarily suspend disbelief and become lost in an engaging movie or novel (see Dreaming, chapters 6 and 11 for discussion). This comes back to the idea, discussed in previous posts, that presence in dreams is associated with spatiotemporal self-location: even lucid dreams are experienced as occurring here and now, even though lucid dreamers know that they are actually lying asleep in bed.

From this, you might conclude that the phenomenology of thinking and of cognitive agency in dreams is comparable to a light switch: the reason that in a majority of dreams, we fail to realize that we are now dreaming is that we simply don’t think about whether we are, and indeed don’t think about much of anything at all. If we did, we would become lucid. The threat of dream deception consequently loses much of its bite: dreams are indeed deceptive, but only because we don’t critically examine or distance ourselves from our dreams while they are unfolding. If we so much as tried to engage in critical thought while dreaming, we would, contra Descartes, be able to tell the difference between dreaming and wakefulness.

I think this view is only partially correct, however. To me, some of the most interesting examples of thinking in dreams are so-called prelucid dreams. In prelucid dreams, dreamers wonder whether they are now dreaming, but either do not come to any conclusion or falsely conclude that they are now awake. Yet, their reasons for doing so are often, from a third-person, epistemological perspective, anything but rational. For instance, dreamers may conclude from the fact that they are standing on a stage, giving a public speech while wearing nothing but their underpants that they must certainly be awake; or they may reason that as they are able to fly or levitate off the ground, this cannot be a dream. Phenomenologically, they have the impression of engaging in a perfectly rational line of reasoning; yet, this impression is deeply misguided (I develop these ideas and discuss a number of empirical examples in Dreaming, chapters 9 and 10).

Things get worse when so-called lucidity lapses are taken into account. Even when they have already realized that they are dreaming, dreamers may still think they are literally sharing the dream with other dream characters, be afraid of performing “dangerous” actions (such as jumping off a cliff), or assume their dream actions to have real-world consequences. For instance, they may try to write down details of their dream while dreaming, so that they will be able to remember them after they have woken up (again, see Dreaming, chapters 9 and 10 for discussion and references to the literature). Of course, one might want to say that such dreams are not fully lucid; but this would gloss over the fact that there appears to be a deep continuity in different forms of conscious thought and cognitive agency between lucid and nonlucid dreams, as well as gradual transitions between them (for a first attempt to measure this difference empirically, see Voss et al. 2013). This suggests that a more nuanced view of thinking in lucid and nonlucid dreams is needed: Thinking in dreams is not quite like using a light switch to suddenly illuminate a room; it is more like playing around with the switch and then becoming distracted, or actually flipping it on and then failing to realize that the light has not, in fact gone on. As often as not, thinking in dreams is associated with partial or apparent rather than with genuine insight.

In Dreaming, I argue that the underlying problem is not so much that thinking is absent in dreams, but that it is frequently corrupted. In a dream, one can have the impression of engaging in rational thought or remembering something about one’s waking life and be completely wrong; the phenomenology of thinking and of knowing is profoundly unreliable and often outright misleading in dreams. Lucid dreams show that rational thought and genuine insight are possible in dreams; but prelucid dreams (as well as lucidity lapses) suggest that they are not recognizable.

Note that this gives rise to a new reading of what it means to say that dreams are deceptive: Where Descartes’ scenario of dream deception has us deceived about the perceptual world and our own bodily existence, examples of cognitive corruption suggest that in dreams, we are deceived about our own cognitive abilities, about our current status as rational, epistemic subjects (for a fuller discussion of what I take to be real-world examples of dream deception, see Dreaming, chapter 10). Moreover, even genuine insight, as in lucid dreams, can exist alongside otherwise irrational thought. We might even want to say that the two ways of characterizing the epistemic relationship between the dream self and the dream world that I described at the beginning of this post are not as different as they may seem. Instead, in many dreams, insight and deception may go hand in hand.

References

Dresler, M., Koch, S., Wehrle, R., Spoormaker, V. I., Holsboer, F., Steiger, A., et al. (2011). Dreamed movement elicits activation in the sensorimotor cortex. Current Biology, 21(21), 1833–1837.

Edwards, C. L., Ruby, P. M., Malinowski, J. E., Bennett, P. D., & Blagrove, M. T. (2013). Dreaming and insight. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 979. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00979.

Erlacher, D., Schädlich, M., Stumbrys, T., & Schredl, M. (2014). Time for actions in lucid dreams: Effects of task modality, length, and complexity. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1013. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.01013.

Gerrans, P. (2014). Pathologies of hyperfamiliarity in dreams, delusions, and deja vu. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 97. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00097.

Gottesmann, C. (2006). The dreaming sleep stage: A new neurobiological model of schizophrenia? Neuroscience, 140, 1105–1115.

Gottesmann, C. (2007). A neurobiological history of dreaming. In D. Barrett & P. McNamara (Eds.), The new science of dreaming: Vol. 1. Biological aspects (pp. 1–51). Westport: Praeger Perspectives.

Hearne, K. (1978). Lucid dreams: An electro-physiological and psychological study.Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Liverpool, England.

Hobson, J. A. (1999). Dreaming as delirium: How the brain goes out of its mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hobson, J. A., Pace-Schott, E. F., & Stickgold, R. (2000). Dreaming and the brain: Toward a cognitive neuroscience of conscious states. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 793–842.

LaBerge, S. (1985). Lucid dreaming: The power of being awake and aware in your dreams. New York: Ballantine.

LaBerge, S. (1988). The Psychophysiology of Lucid Dreaming. In J. Gackenbach & S. LaBerge (Eds.), Conscious mind, sleeping brain: Perspectives on lucid dreaming (pp. 135–153). New York: Plenum Press.

Metzinger, T. (2003). Being no one: The self-model theory of subjectivity. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sartre, J.-P. (1940). L’imaginaire: Psychologie phénoménologique de l’imagination. Paris: Gallimard.

Voss, U. & Hobson, A. (2015). What is the State-of-the-Art on Lucid Dreaming? – Recent Advances and Questions for Future Research. In T. Metzinger & J. M. Windt (Eds). Open MIND: 38(T). Frankfurt am Main: MIND Group. doi: 10.15502/9783958570306

Voss, U., Holzmann, R., Hobson, A., Paulus, W., Koppehele-Gossel, J., Klimke, A., et al. (2014). Induction of self awareness in dreams through frontal low current stimulation of gamma activity. Nature Neuroscience, 17(6), 810–812. doi:10.1038/nn.3719.

Voss, U., Holzmann, R., Tuin, I., & Hobson, J. A. (2009). Lucid dreaming: A state of consciousness with features of both waking and non-lucid dreaming. Sleep, 32(9), 1191–1200.

Voss, U., Schermelleh-Engel, K., Windt, J. M., Frenzel, C., & Hobson, J. A. (2013). Measuring consciousness in dreams: The lucidity and consciousness in dreams scale. Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 8–21.

Windt, J. M. (2015a). Dreaming: a conceptual framework for philosophy of mind and empirical research. Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England: MIT Press.

Windt, J. M. (2015b), “Dreams and Dreaming“, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2015/entries/dreams-dreaming/>.

Windt, J. M., & Metzinger, T. (2007). The philosophy of dreaming and self-consciousness: What happens to the experiential subject during the dream state? In D. Barrett & P. McNamara (Eds.), The new science of dreaming: Vol. 3. Cultural and theoretical perspectives (pp. 193–248). Westport: Praeger Perspectives.

Windt, J. M., & Noreika, V. (2011). How to integrate dreaming into a general theory of consciousness: A critical review of existing positions and suggestions for future research. Consciousness and Cognition, 20(4), 1091–1107.