Why did some organisms switch from relying just on reflexive—i.e. purely perceptually-driven—interactions with the world to also employing the tools of representational decision making? What adaptive and other benefits does the reliance on representational decision making yield? Today, I sketch aspects of the answers to these questions; for more details, see chapters 4-6 of my book.

To set out an account of the evolution of representational decision making, it first needs to be noted that it is widely acknowledged that representational decision making comes with a number of cognitive costs: it tends to be slower than reflexive decision making and require more cognitive resources such as concentration and attention. Given this, what benefits does representational decision making yield that can, at least at times, outweigh these costs—and thus explain its evolution?

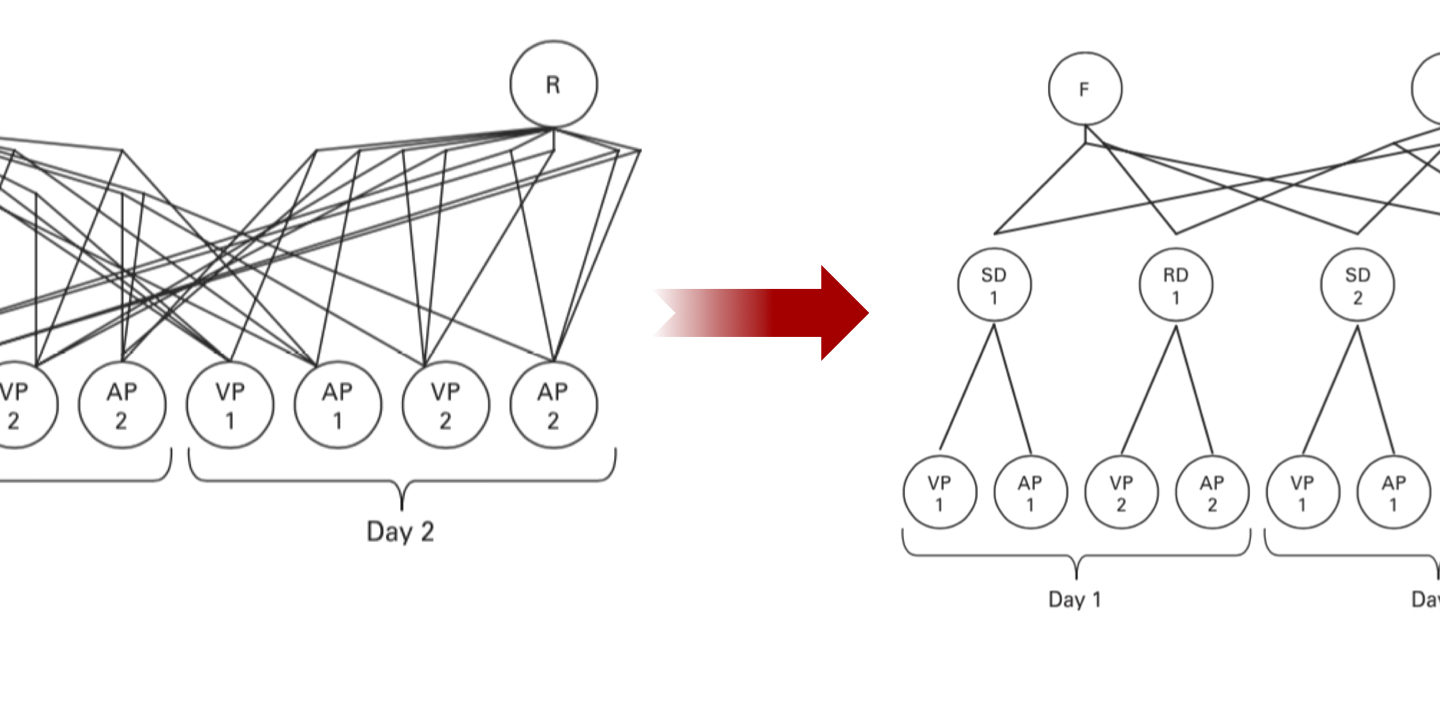

When it comes to the evolution of cognitive representational decision making, the key point to note is that it allows organisms to go from a table of reflexes that is likely to contain much redundancy to one that is much smaller. Purely reflexive organisms will often need to associate many different perceptual states to the same behavioral response in order to behave adaptively. (This is a key insight of Sterelny’s 2003 account of human cognitive evolution.[1]) Representational decision makers, though, can avoid this redundancy: they can determine the appropriate behavioral response to the world by first “chunking” the information received from their perceptual systems, and then reacting to combinations of these “chunked” states. In turn, this brings two kinds of adaptive benefits to these organisms. First, it can make it easier for them to adjust to changes in their environment: organisms do not need to alter the large number of associations between perceptual states and behavioral responses, but merely the (generally) fewer associations between representations of the state of the world and behavioral responses. On the other hand, cognitive representational decision making can streamline an organism’s cognitive and neural system: reliance on chunked information can enable the organisms to make more efficient use of its neural resources.

Something very similar is true when it comes to the evolution of conative representational decision making. However, instead of streamlining a table of behavioral responses, it enables organisms to avoid the table altogether, and just compute the response to the situation. This, too, can make it easier to adjust to changed environments and helps organisms to streamline their cognitive and neural systems.

Given all of this, when is there an adaptive advantage in cognitive and / or conative representational decision making? Abstractly speaking, this will be the case when the costs of representational decision making—losses in decision making speed and increased use of cognitive resources—are outweighed by its benefits—easier adjustment to changed environments and increased cognitive and neural efficiency. What does this mean more concretely? It suggests that representational decision making is adaptive in cases where adaptive behavioral responding cannot be made dependent on just a few perceptual states, where organisms can compute their behavioral response relatively easily, and where the environment changes relatively frequently. Examples of such cases are certain kinds of social, spatial, or causal environments. For example, consider the classic challenges of great ape social living.[2] In these environments, the choice of which coalition to join (say) is an adaptively important decision associated with a large and complex set of perceptual contingencies that needs to change frequently (e.g. with changes in the composition of the group), but where this decision can often be relatively leisurely computed by attending to surprisingly few variables, such as coalition size and one’s place in the social hierarchy.

Interestingly, this conclusion of which environments favor representational decision making matches the implications of other, related accounts—such as those of Sterelny or Millikan.[3] However, here, this conclusion is arrived at very differently from what is the case in these other accounts: on my account, the evolution of representational decision making is driven not by enabling organisms to do things that purely reflexive organisms cannot do—rather, it is driven by it enabling organisms to do the same things better. In short: despite appearances to the contrary, representational decision making is—in certain circumstances—more, not less, efficient than reflexive decision making. In the next and final guest post, I will bring out some implications of this conclusion.

[1] See Sterelny, K. (2003). Thought in a Hostile World. Oxford: Blackwell.

[2] A. Whiten and R. W. Byrne, eds., Machiavellian Intelligence Ii: Extensions and Evaluations (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

[3] Ruth Millikan, Varieties of Meaning (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002).

Interesting argument, but I’m skeptical. I think it is interesting to go back to the very beginning, and think about the very first, most primitive, type of representation. There are perhaps several candidates, but the one that strikes me is circadian rhythmicity: internal systems that use levels of specific molecules to represent the time of day. Circadian rhythms are found in virtually all plants and animals, and even in bacteria.

What is their value? Most importantly, they serve as a surrogate for light. Crucially, though, they are more reliable. Light can be temporarily interrupted by a wide variety of perturbations. The molecular concentrations that represent time of day are much more robust. If not for this factor, most of the responses that are tied to circadian rhythms could equally well be tied to light levels.

In this most primitive case, then, it seems that the function of representation is not to simplify stimulus-response mechanisms, but rather to compensate for the difficulty in extracting important information directly from the environment.

I agree that circadian rhythms are very interesting in terms of biological decision making. However, I don’t think they pose a problem for the account laid out here (and more fully in the book!). Exactly what is going on here will depend on the details of the case a bit, but if it is the case that an organism does not react to it’s light-based perceptions (e.g. how dark it is), but rather relies on systems that use the amount of ambient light merely as an input to form an internal state that represents whether it is day or night, then that would be a good example of cognitive representational decision making. (In fact, in the book, I use a case a bit like this to illustrate this.) On the other hand, if the circadian rhythm functions more like an internal clock, then that would be reflexive: the organism would just react to the (ap)perception of its internal state. (This last point relates to something that I didn’t get the chance to make clearer in the above post: I understand perception broadly, to also include the detection of internal states.)

Thanks for this very insightful comment!

Cool work here, Armin! I’m curious about how you distinguish your account from the other related accounts of representational decision making. You say that representational decision making evolved to enable organisms to do the same things better. By do the same things, do you make make the same decisions? And by better, do you mean more efficient? I think it would help to have an example to illustrate this. So, on your account, what would an ape’s reflexive decision making about which coalition to join look like? And how would this same decision (if it’s the same decision) look like with representational decision making?

Hi Shannon! Thanks so much for the kinds words. You are exactly right with how you interpreted what I said; here is an example that might make this clearer still.

Assume an organism has to decide what coalition to join. Purely reflexively, that would (likely) require associating a vast number of different perceptions to a given behavioral outcome. So: each way an offer to join an (attractive, for simplicity) coalition could be perceived would need to be associated with joining behavior. A cognitive representational decision maker can simplify this by (say) first generating a representation of an (attractive) coalition being present, and then generating a representation of an offer to join a coalition having been made. The organism can then combine these two representations to form a representation that an offer to join an (attractive) coalition has been made. It can then associate that representation with acceptance behavior. This is useful, as the intermediate representations order the perceptions. The reflexive organism distinguishes an offer to join a coalition of 5 higher-ranking individuals made with a hand-gesture from an offer to join that same coalition made with an eye movement, and so on, and all of these from offers to join similarly attractive (we may assume) coalitions of 7 lower-ranking individuals. It is this kind of redundancy that a cognitive representational decision maker can avoid. (The picture above the post is meant to illustrate this.) An upshot of this is that it is not the case that reflexive decision makers could not make these kinds of decisions appropriately; it is just that they would make them less efficiently overall.

Conative representations add several further wrinkles to this, but I hope the above helps a little at least!

This does help. Thanks! It certainly seems plausible that for some decisions, an organism could make the same decision reflexively and representationally with the only real difference being cognitive and neural efficiency. (This of course generates other benefits, like freeing up the organism to focus on other decision problems or responding quickly to time-sensitive decisions.) I’m wondering if the advantage of using representational decision making involves more than just efficiency (and its downstream benefits), though. It seems quite plausible that some decisions come about only because an organism can represent the options (or form meta-representations), and that without these abilities an organism just would not have made that decision. So I guess what I’m wondering is how committed you are to the idea that for any decision, it plausibly could have been made either reflexively or representationally, holding everything else fixed.

Another good question. I am inclined to agree that there are some decisions that it is hard to make purely reflexively. Some causal decisions come to mind: for example, if an organism can represent that A causes both B and C, they might be instantly inclined to intervene on A—and not C—to bring about B; this would not need to be associatively learned. However, that said, I still think that sufficiently sophisticated reflexive organisms can mimic this kind of decision-making well. For example, they would need to just be able to learn sufficiently quickly that intervening on A is more productive in bringing about B than intervening on C. For this sort of reason, I don’t think it is plausible to locate the adaptive benefits of representational decision making solely on the ability to make some kinds of decisions. That said: the account above is consistent with there being some other benefits of representational decision making as well—it just emphasizes that there is another set of benefits as well that don’t depend on the ability to make a novel kind of decision.

I’m interested in being precise about what the difference may be between ‘representational decision making’ and ‘reflexive decision making’ at the level of neural architecture. It seems to me that even reflexive decision making is, in practice, usually the result of several layers of neural processing, so the action is not being driven directly off sensory inputs, but off intermediate layers of processing (eg blob detection, edge detection), even if these are kept to a minimum in order to keep the response time low. So what is the difference between driving an action reflexively off an intermediate layer of processed data, and representational decision making. I think it comes into play when any useful feature lasts for more than one cognitive cycle (of a few 100 ms), and even more so when it remains valid over long times (seconds, hours, days, a lifetime or generations, if we bring culture into play). It then becomes worth having a predictive representation of that persisting context against which fast reflexive processing within the cognitive cycle can be organised; and a second task has to be done within each cognitive cycle: to update the persisting representation.

I agree with much of what you note here. In particular, there is good reason to think that perception is itself hierarchically organized. However, as long as some distinction between perception and cognition can be maintained – which currently still seems to be the best-supported position – the account above can get off the ground. (In fact, the account could even be made to work with merely a distinction of degree between perception and cognition – a position for which I have some sympathy. In that case, the distinction between reflexive and representational decision making would only be one of degree as well. While introducing some interesting complexities, much of the above account would remain unchanged.)

Thanks for your interesting blogs and replies. My comments on the relation to neural architectures are based on the mechanisms of consciousness that I wrote about here:

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Mechanisms-Consciousness-How-consciousness-works-ebook/dp/B01N4LPLAD

Thanks a lot for your comments! I am glad that you found the posts and discussions useful. Your book looks interesting, too.