Recall the example discussed in my earlier post:

Jill and Jack: Jill fears (without good reason) that Jack is angry with her. As a result of her fear, Jack’s face looks angry to her when she sees it. If you saw Jack, you’d see his neutral expression for what it is. There’s no need for Jill to jump to conclusions from what she sees. Her fear’s influence on perceptual experience makes it simpler for her: she can just believe her eyes.

Concerning this example I raised the following puzzle: “Is it reasonable for Jill to believe her eyes, when her visual experience is a projection from an unreasonable fear or presumption? It might seem that the answer is Yes. What else is Jill supposed to believe, given that she has no idea her fear has been projected onto her experience? … On the other hand, there’s something fishy about Jill’s strengthening her fear on the basis of her perception, given the role of the fear in generating the key aspects of her visual experience – the aspects that make the fear seem reasonable. If Jill’s fear starts out unreasonable, how could it become reasonable, just by shaping the crucial contents of a visual experience?”

This problem has many potential instances. Here are some others:

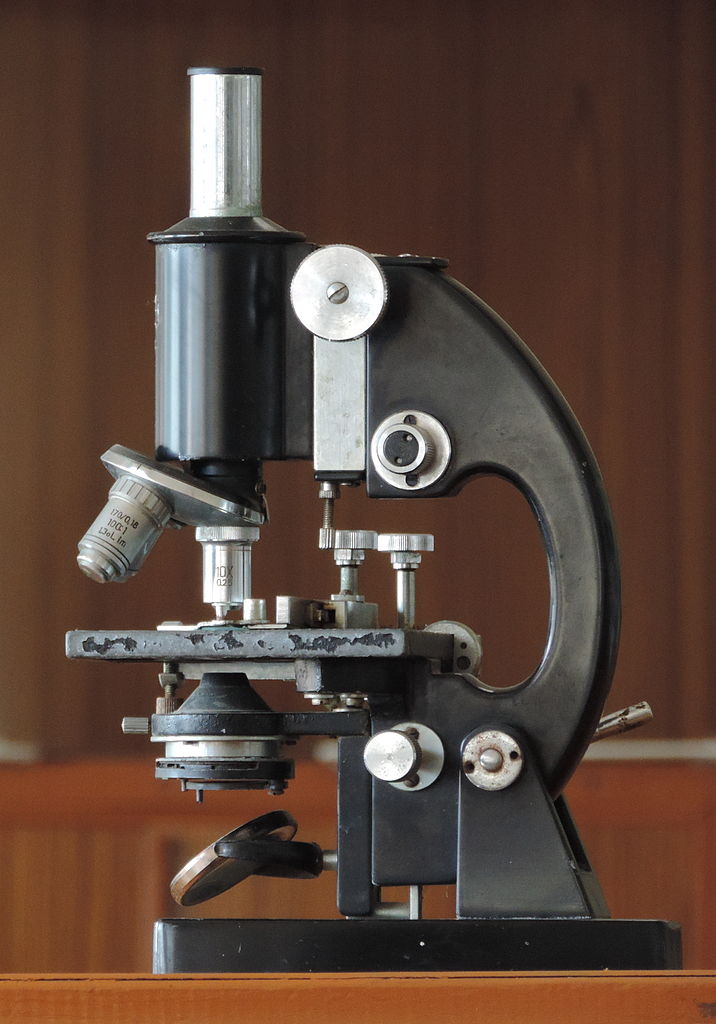

Preformationism: When spermist preformationists (who favored the hypothesis that sperm cells contained embryos) look at sperm cells under a microscope, their experiences have embryo-content, due to their favoring preformationism. They go on to believe that the embryos contain sperm cells, and to strengthen their confidence that preformationism is true.

Vivek: Vivek is a vain performer. He is irrationally overconfident that his audiences as well as casual observers look at him with approval. When he sees their faces, he has visual experiences in which those faces look approving, even when their expressions are in fact neutral.

Gun: After seeing a face of a man who is black as a conscious prime, a participant whose task (in an experiment) is to decide whether a subsequent object he is shown is a tool or a gun has a visual experience of a gun when seeing a pair of pliers. He goes on to believe that the object is a gun, and the outlook which associates between black men and guns is strengthened.

Threat illusion: To a man whose mind manifests culturally entrenched racial attitudes toward black men, a boy playing in a playground who is black looks to the man like a much older teenager dangerously wielding a gun. The illusion (age, threat) arises because of Man’s racial attitude that black men and boys are dangerous. The perception of threat occurs in the man’s visual experience.

These cases all give rise to the same problem as Jill’s situation when she sees Jack.

The problem illustrated by these cases has many potential solutions. Some solutions say that the correct answer is Yes, some say it is No, some say it is both Yes and No, depending on the dimension of reasonableness at issue. For any potential solution, a full defense would identify the features that would make it reasonable or unreasonable for the subjects in the examples to believe their eyes.

Normally, perceptual experiences have a power to help justify beliefs formed on the basis of those experiences. The philosophical question about these cases is whether the power of experiences to justify believing one’s eyes is reduced by the influence of psychological precursors, or whether that power is sustained despite such influence.

The solution I defend in The Rationality of Perception is that the correct answer is No, due to the relationship between the psychological precursor and the perceptual experience. That relationship, I argue, can be inference: perceptual experiences can be inferred from psychological precursors. When the relations is inference, and the perceptual experience is inferred from the psychological precursors, then the experience can lose epistemic power.

The main point of the book is to explain how experiences could arise from inference. The idea that perception results from inference has a long history in Psychology. But the kind of inference at issue in Psychology is usually not the kind at issue in The Rationality of Perception. What’s at issue in The Rationality of Perception is whether perceptual experiences can result from the kind of inferences that redounds well or badly on one’s rational standing.

Hi Susanna, I’m wondering if you can say how you see the relationship between (i) your ‘No’ answer to the Jack & Jill question (which I would also give) and (ii) the idea that perceptual experiences can be based on inference. I can see how this idea would give one way of explaining why experiences like Jill’s can’t justify beliefs, but why should I think it’s the only way or even the best one? In particular, why not think that even if Jill’s fear influences how things appear to her in a non-inferential way, that’s enough to defeat, to that extent, the power of the experience to make belief reasonable?

Thanks for asking, John. There are most certainly many ways to explain what accounts for the epistemic weakening of experiences in these cases, if one answers No. For instance, reliabilists might try to argue that the problem is unreliability, and this type of response to the cases has been developed by Jack Lyons (in “Circularity, Reliability, and Cognitive Penetrability” (2011) and “Inferentialism and Cognitive Penetration of Experience” (2016)) and Harman Ghijsen (in “The Real Problem with Cognitive Penetration” (2016)). A differently externalist response by Hamid Vahid (in “Cognitive Penetration, the Downgrade Principle, and Extended Cognition” (2014)) locates the source of the epistemic weakening in the sensory-motor contingencies registered by the subjects.

And there are also (as Ram suggested in his comment on first post) non-inferentialist accounts that locate the source of the epistemic weakening inside the subject’s mind. For instance, one might try to argue that in these cases the subject always has a defeater: there is some information she has which should give her pause before believing her eyes, such as the fact that her experience is congenial to what she antecedently feared, hoped, believed, or suspected.

Alternatively, one might try to locate the culprit inside the subject’s mind, but outside the her awareness. I defended such a view myself in “The Epistemic Impact of the Etiology of Experience” (2013, in a symposium in Philosophical Studies, where Richard Fumerton and Michael Huemer both argue for answering Yes, and Matt McGrath floated a version of inferentialism).

The most flat-footed way to defend the inferentialist approach would try to show that it is better than these alternatives. In Chapter 6 of the book (“How Experiences Can Lose Power from Inference”), I criticize some reliabilist arguments for what I called “epistemic downgrade” – the epistemic weakening of experience, and in Chapter 4 (“Epistemic Downgrade”), I argue that the subject does not always have a defeater. If recognizing that your experience conformed to your expectations was enough make it unreasonable (or even just less reasonable than usual) to believe your eyes, we’d hardly ever have reason to believe our eyes! When I woke up this morning I expected to find myself in my house, and my experience conformed to this expectation. We’d be on the road to excessive epistemic downgrade if that conformity was enough to generate a defeater.

Although I criticize several alternatives to inferentialism, my defense of it doesn’t have an abductive form. I think that kind of defense would be premature, before we have a better understanding of what exactly the inferential approach says, and how it could possibly be true. So the defense of inferentialism I offer in the book is what I call a “constructive defense”. The constructive defense aims to explain why inferentialism is well-motivated, how it analyzes key features of the cases, and perhaps most importantly, what experience and inference are, such that experiences could be conclusions of inference.

Very interesting and an “I have not thought of this before as an amateur trying to learn” proposition. Leads me to have to buy Susanna’s book post haste.