Unless you have the good fortune to be shielded from the latest obsessions of social media, you heard last week about “the dress”, an image of a dress that some people see as white and gold while others see it as blue and black, with a few able to switch between the two interpretations.

A week or so late to the game, and now that everyone has made up their minds about what color the dress is and moved on to discussing other matters, the Brains blog is pleased to be hosting a roundtable discussion among several distinguished philosophers, who address the science of the phenomenon as well as deeper questions about whether this all just goes to show that everything is, like, only your opinion, man.

Contributing to the discussion are Kathleen Akins (Simon Fraser University), Keith Allen (University of York, UK), Brit Brogaard (University of Miami), Alex Byrne (MIT) and David Hilbert (University of Illinois, Chicago), Jonathan Cohen (University of California, San Diego), Carolyn Jennings (University of California, Merced), and Yasmina Jraissati (American University of Beirut). [UPDATE: See also the recent guest post by Justin Broackes (Brown).] To expand their contributions, just click their names below. And feel free to continue the discussion in the comments!

Header image source: @budoucha, via Kathleen Akins

A neuroscientist and friend Bevil Conway has written a nice piece on this, which you can find on Wired: https://www.wired.com/2015/02/science-one-agrees-color-dress/ Excellent diagrams!But for the record, here is on my own take on The Dress. There are a number of different things going on in this image that lead people (or more precisely, their visual systems) to see the dress as having different colours. I suspect the central mechanism that explains much of the disagreement is just colour constancy. Throughout the day, the colour of the light which illuminates any natural scene changes in predominant wavelength. So, outdoors, the colour of sunlight reflected from an object depends upon the time of day, position of the sun in the sky, position of the viewer relative to the sun and so on. Indoors, in artificial settings, the colour of light depends upon which artificial light source you are using—incandescent (yellow), fluorescent (a variety of colours given filters), halogen (very intense light across the whole spectrum), etc. Just as the human visual system adapts for changes in light intensity, the retina and visual brain adapt to these changes in predominant wavelength through adjustment of contrast mechanisms. You, the person, rarely notice these adaptations, unless it’s too dark to read, or someone has suddenly turned on the light at night—or someone asks you about The Dress. So, for example, even though an incandescent light is predominantly yellow/orange, when you turn on your incandescent desk lamp, you don’t think that your shirt has suddenly turned orange, even though, in fact, your shirt now reflects predominantly yellow-orange light. If you were to take a photograph of your white shirt, and then cut a small window into a piece of white copier paper, and place it over the image of the shirt, you would be able to see that the shirt really does reflect mostly orange-yellow light. You can see this clearly in the Wired illustrations.

A neuroscientist and friend Bevil Conway has written a nice piece on this, which you can find on Wired: https://www.wired.com/2015/02/science-one-agrees-color-dress/ Excellent diagrams!But for the record, here is on my own take on The Dress. There are a number of different things going on in this image that lead people (or more precisely, their visual systems) to see the dress as having different colours. I suspect the central mechanism that explains much of the disagreement is just colour constancy. Throughout the day, the colour of the light which illuminates any natural scene changes in predominant wavelength. So, outdoors, the colour of sunlight reflected from an object depends upon the time of day, position of the sun in the sky, position of the viewer relative to the sun and so on. Indoors, in artificial settings, the colour of light depends upon which artificial light source you are using—incandescent (yellow), fluorescent (a variety of colours given filters), halogen (very intense light across the whole spectrum), etc. Just as the human visual system adapts for changes in light intensity, the retina and visual brain adapt to these changes in predominant wavelength through adjustment of contrast mechanisms. You, the person, rarely notice these adaptations, unless it’s too dark to read, or someone has suddenly turned on the light at night—or someone asks you about The Dress. So, for example, even though an incandescent light is predominantly yellow/orange, when you turn on your incandescent desk lamp, you don’t think that your shirt has suddenly turned orange, even though, in fact, your shirt now reflects predominantly yellow-orange light. If you were to take a photograph of your white shirt, and then cut a small window into a piece of white copier paper, and place it over the image of the shirt, you would be able to see that the shirt really does reflect mostly orange-yellow light. You can see this clearly in the Wired illustrations.

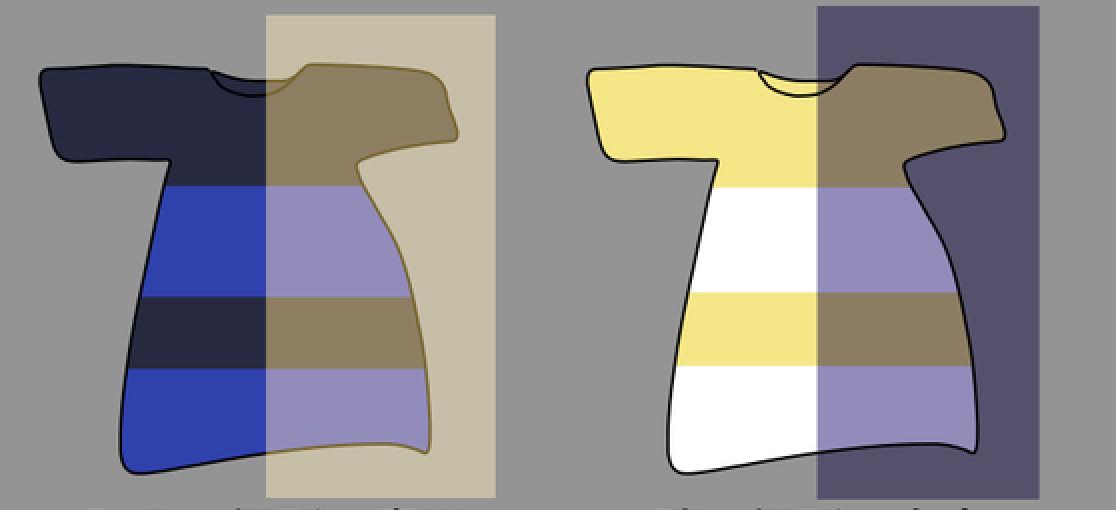

As I said, there are a number of things going on in this photograph, but colour constancy is the main one. I myself see The Dress as white and gold. I’m just that sort of person (no, that was a joke). In the Wired article, you can see that the jacket is reflecting mostly blue light. My visual system interprets the jacket as white but as illuminated by blue light. If you shone a blue light on a white and gold dress, and then took at a photograph of the dress, you would see that the white stripes of the dress reflect blue light (because the light is blue) and the gold stripes would reflect a very dark, muddy colour, a mixture of blue and yellow light at a low intensity. Actually, the light reflected from a shiny gold material would also have white ‘glints’—specular reflectance from the gold material, another ‘hint’ in The Dress photograph that the dress is gold. This is why I see The Dress as white and gold, because a white and gold dress, seen under a dim blue light, would look just like this in its image (or photograph).

Other people see the dress as black and blue because their visual systems makes a different ‘guess’ about the colour of the light. Their visual systems interpret the light as white, as emitting all wavelengths of light equally. Given an actual black and blue dress and ‘white’ light source, a photograph of the this dress would show the blue stripes as reflecting blue light, and the black stripes as reflecting almost no light. The photograph would be much closer to the true colours of the dress: there would be blue and black stripes in both.

As you can see from the Wired photograph, both of these interpretations work, more or less, just as a (rare) matter of chance. If your brain interprets the light as blue, you see a white and gold dress; if your brain interprets the light as white (or ‘colourless’) then you see the The Dress as black and blue. In fact, the fact that the dark stripes are shiny, adds to the plausibility of the gold/white interpretation. And because the viewer has never seen The Dress before, it’s up to the brain to figure out which interpretation is more likely. Both interpretations work, so some brains see one thing, and some brains see the other. In fact, some people can make the dress switch back and forth in colour at will, just like some people can make a Necker cube, switch back and forth. It is nice colour illusion, one of the very few natural illusions of this kind.

One reason why we rarely have colour illusions is because, in any natural scene, the scene is complex enough to yield a stable interpretation of object colour. The standard artificial illusions for shape and size depend upon reducing the information within the scene (e.g. Necker cubes have no shading information, and the Ames room reduces depth perception). The Dress manages to do much the same thing simply by ‘hogging’ the photograph — taking up most of the photograph—and thereby providing very little background information.

As any philosopher will have noticed, the above interpretation depends upon a realist view about colour. (Shockingly, I think that the dress is either black and blue or white and gold — and that facts about The Dress’s colours warrant specific shoe/accessory choices.) However, this realism follows from some complex views about human colour vision, namely: (1) Seeing object surfaces as having colours, just like seeing surfaces as light or dark, is a complex task, one that usually occurs sub-personally but can at times require our conscious attention (witness ‘reversing’ the dress colour combination); (2) the luminance and chromatic systems both begin with contrast encodings, the most useful and most general form of visual information for seeing objects; and (3) from these luminance and chromatic contrast encodings, various properties of the world are discerned — and; (4) it is from these properties, not from sensations (be they colour of grayscale), that we come to see surface colours and object albedo (surface lightness/darkness). In other words, seeing surface colour is a high-level cognitive achievement, one that children ‘grow into’ at the ancient age of 3 and onwards, given suitable training with colour names.

Where does this leave us? On the one hand, the cognitive nature of colour perception is what makes it immune to illusion in the ordinary case, when viewing complex natural scenes. This is why The Dress is so…shocking. There are usually too many properties of the scene that coalesce around a single interpretation of object colour. On the other hand, this is what makes colour perception such a prime subject for colour illusions. If we have no access to the properties of scenes that would normally allow us to see stable surface colours, we are easily ‘fooled’ by these artificial stimuli. Notably, no one about to buy The Dress, or to try it on, would be in any doubt about its colours—or be able to convince their shopping partners that The Dress is gold and white when it is black and blue. But the photograph of the dress is another story.

Do the radically different experiences of ‘the dress’ show us that things aren’t really coloured—that colours are ‘invented by the brain’—or else that colours are relational properties—that the dress is white-and-gold-for-me, but blue-and-black-for-you? However tempting these responses are, the details of the case don’t really bear them out. The issue isn’t really the dress, but a photograph of the dress—and a poor quality photograph at that. Everyone agrees (or would agree, if they saw it in different conditions) that the dress itself is black and blue. And since many people won’t have seen the dress ‘in person’, but only better photographs of the dress, there’s no reason to suppose that there is a general problem about photographic representations of colour. An obvious explanation of this widespread agreement about the colour of the dress itself is that colours are non-relational properties of things that we all, more or less successfully, perceive.But what about the photograph? It might be suggested that those (myself included) who see the photograph as representing a white and gold dress at least can’t be wrong about that. But we are familiar with visual illusions in which things appear other than they really are. One of the striking things about the photograph of the dress is that it is an illusion to which only some people are susceptible. But although admitting that only some of us misperceive the photograph is unsettling, it is not ad hoc, since everyone agrees on the colour of the dress it represents.

Do the radically different experiences of ‘the dress’ show us that things aren’t really coloured—that colours are ‘invented by the brain’—or else that colours are relational properties—that the dress is white-and-gold-for-me, but blue-and-black-for-you? However tempting these responses are, the details of the case don’t really bear them out. The issue isn’t really the dress, but a photograph of the dress—and a poor quality photograph at that. Everyone agrees (or would agree, if they saw it in different conditions) that the dress itself is black and blue. And since many people won’t have seen the dress ‘in person’, but only better photographs of the dress, there’s no reason to suppose that there is a general problem about photographic representations of colour. An obvious explanation of this widespread agreement about the colour of the dress itself is that colours are non-relational properties of things that we all, more or less successfully, perceive.But what about the photograph? It might be suggested that those (myself included) who see the photograph as representing a white and gold dress at least can’t be wrong about that. But we are familiar with visual illusions in which things appear other than they really are. One of the striking things about the photograph of the dress is that it is an illusion to which only some people are susceptible. But although admitting that only some of us misperceive the photograph is unsettling, it is not ad hoc, since everyone agrees on the colour of the dress it represents.

Colors are not really low-level properties. They are computed rather late in the visual system. In fact, there is some evidence to suggest that they are generated outside of the visual cortex (see Brogaard, B & Gatzia, DA, “Is Color experience Cognitively Penetrable?”, Topics in Cognitive Science, In Press). So, when light reaches out eyes, we don’t automatically see colors. Our brains need to go through a lot of processing and interpretation of what the environment is like. A great example of this is the checker illusion.This illusion occurs because our perceptual system adjusts for changes in the “the spectral power distribution” (SPD) of the illuminant, thus treating an image the same way it would treat an object in natural illumination conditions. In our environment the level of energy of the light at each wavelength in the visible spectrum (SPD) varies greatly across different light sources (illuminants) and different times of the day. Cool white fluorescent light and sunlight have radically different SPDs. Sunlight has vastly greater amounts of energy in the blue and green portions of the spectrum, which explains why an item of clothing may look very different in the store and when worn outside on a sunny day. The SPD of sunlight also varies throughout the day. Sunlight at midday contains a greater proportion of blue light than sunlight in the morning or afternoon, which contains higher quantities of light in the yellow and red regions of the color spectrum. Sunlight in the shade, when it is not overcast, contains even greater amounts of blue light.

Colors are not really low-level properties. They are computed rather late in the visual system. In fact, there is some evidence to suggest that they are generated outside of the visual cortex (see Brogaard, B & Gatzia, DA, “Is Color experience Cognitively Penetrable?”, Topics in Cognitive Science, In Press). So, when light reaches out eyes, we don’t automatically see colors. Our brains need to go through a lot of processing and interpretation of what the environment is like. A great example of this is the checker illusion.This illusion occurs because our perceptual system adjusts for changes in the “the spectral power distribution” (SPD) of the illuminant, thus treating an image the same way it would treat an object in natural illumination conditions. In our environment the level of energy of the light at each wavelength in the visible spectrum (SPD) varies greatly across different light sources (illuminants) and different times of the day. Cool white fluorescent light and sunlight have radically different SPDs. Sunlight has vastly greater amounts of energy in the blue and green portions of the spectrum, which explains why an item of clothing may look very different in the store and when worn outside on a sunny day. The SPD of sunlight also varies throughout the day. Sunlight at midday contains a greater proportion of blue light than sunlight in the morning or afternoon, which contains higher quantities of light in the yellow and red regions of the color spectrum. Sunlight in the shade, when it is not overcast, contains even greater amounts of blue light.

In the picture of the dress the environment is clearly presented to us. It is left vague whether we are seeing the dress in bright sunlight, inside illuminated by artificial light or in the shade. But our brains fixates on one of those environments. When our brains interprets the background as being sunny, we see the dress as blue and black. If our brains takes the dress to be in the shade, then it will be more likely to look white and gold.

Three observations and one recommendation about the dress.1) The question of why it looks different to different people (and changes appearance for some) is a question for color science, not philosophy. It is a question about the workings of the human visual system, not a question about color language, color concepts, the inverted spectrum, or anything else for which the tools of philosophy might be relevant.

Three observations and one recommendation about the dress.1) The question of why it looks different to different people (and changes appearance for some) is a question for color science, not philosophy. It is a question about the workings of the human visual system, not a question about color language, color concepts, the inverted spectrum, or anything else for which the tools of philosophy might be relevant.

2) There is widespread lip service (among both philosophers and non-philosophers) paid to the claim that color is a subjective phenomenon, on the grounds that color appearance varies with the characteristics of the perceiver. Despite this, the reaction to a convincing example of such variation in color appearance was alternately (a) disbelief, and (b) a massive investment of time in trying to understand how what everyone professes to believe happens actually happened.

3) People have an intense commitment to knowing the real colors of things. The debate was not only—or even primarily—about the interesting questions concerning color appearance. People wanted to know the color of the dress.

Recommendation: philosophers should stop saying that color is subjective. It’s not true in any interesting sense and, although we can coerce lip service by sophistical argument, the vulgar really don’t believe it.

Explaining why the dress looks two different ways is straightforward, at least in broad strokes: there’s bluish chromatic content in the picture, but too few cues to establish whether that content should be assigned to the surface (which would mean treating the dress as blue/black) or the illuminant (which would mean describing the dress in a way that discounts for the chromatic content, hence as white/gold). Hence there are two stable interpretations available to the perceptual system.What makes the case interesting in ways that go beyond this familiar phenomenon is the difference it highlights between perceiving the world and perceiving pictures. Perceptual ambiguities like that involving the dress do arise in the world, but (at least, outside the controlled conditions of the lab) are rarely so persistent. After all, in the world, visual systems have or can easily obtain (when we walk around or shift our gaze) more cues about both surface and illuminant — e.g., data about how the illuminant affects objects of known colors (familiar fruit types, familiar clothing items, our own skin), statistical relations between chromatic content and lightness, etc. And these data can resolve outstanding ambiguities. The persistent ambiguity of the dress is in this way essentially pictorial: it depends on the relative unavailability of such additional, disambiguating data under conditions of picture perception. This is an ambiguity not about the dress, but about “The Dress”.

Explaining why the dress looks two different ways is straightforward, at least in broad strokes: there’s bluish chromatic content in the picture, but too few cues to establish whether that content should be assigned to the surface (which would mean treating the dress as blue/black) or the illuminant (which would mean describing the dress in a way that discounts for the chromatic content, hence as white/gold). Hence there are two stable interpretations available to the perceptual system.What makes the case interesting in ways that go beyond this familiar phenomenon is the difference it highlights between perceiving the world and perceiving pictures. Perceptual ambiguities like that involving the dress do arise in the world, but (at least, outside the controlled conditions of the lab) are rarely so persistent. After all, in the world, visual systems have or can easily obtain (when we walk around or shift our gaze) more cues about both surface and illuminant — e.g., data about how the illuminant affects objects of known colors (familiar fruit types, familiar clothing items, our own skin), statistical relations between chromatic content and lightness, etc. And these data can resolve outstanding ambiguities. The persistent ambiguity of the dress is in this way essentially pictorial: it depends on the relative unavailability of such additional, disambiguating data under conditions of picture perception. This is an ambiguity not about the dress, but about “The Dress”.

For most of us, #dressgate is not about an actual dress, but about an ambiguous image of a dress, and about the source(s) of that ambiguity. Any of the following factors may be relevant: a) physiological differences in the eyes and/or sensory system, b) differences in the prior light setting of the viewer, c) differences in the image and/or viewing screen, d) differences in pre-conscious assumptions, e) differences in attention/focus, and f) conceptual/linguistic differences. For those who can see both versions of the image, the crucial factor between white/gold and blue/black is likely d and/or e. These factors best explain why the same person can look at the same image in the same lighting conditions and see the dress as “100% blue and black” in one moment and “gold and white…100%” in the next. Yet, there is more to this debate than color constancy and assumptions about light. For one, these factors do not appear to make much of an impact on those who see the dress as only blue/brown. For another, they do not tell us why some cannot see both white/gold and blue/black, despite trying the many different techniques. The remaining conflict probably comes down to either f) or some combination of a), b), and c). It is f) that I find the most interesting and which I think has been discussed the least.Here is the problem: most of us come into this debate first hearing that there are two options: white/gold or blue/black. Since the dress has neither white nor black in it, our willingness to side with one or the other camp may come down to the flexibility of our white and black color concepts. Some may have an inflexible white concept: In one video, the speaker “proves” that the dress is blue and black by selecting shades of blue and brown and arguing that shades from light to medium blue cannot be taken to be white (“it’s never white”), whereas shades from light brown to dark brown can be taken to be black (“it’s like a brown color. So I say it’s black”). Others may have an inflexible black concept: In my own experience of viewing the image, it is much more difficult for me to see the dress as blue and black than white and gold. But I have found that I often take items sold as black to be non-black (usually dark blue). Thus, I suspect that my concept of black is less flexible than for others. So different color concepts are likely playing a role. Yet, I don’t think there is one true cause of #dressgate. If anything, I think it is because so many factors involved and are so difficult to tease apart that this controversy has had so much purchase.

For most of us, #dressgate is not about an actual dress, but about an ambiguous image of a dress, and about the source(s) of that ambiguity. Any of the following factors may be relevant: a) physiological differences in the eyes and/or sensory system, b) differences in the prior light setting of the viewer, c) differences in the image and/or viewing screen, d) differences in pre-conscious assumptions, e) differences in attention/focus, and f) conceptual/linguistic differences. For those who can see both versions of the image, the crucial factor between white/gold and blue/black is likely d and/or e. These factors best explain why the same person can look at the same image in the same lighting conditions and see the dress as “100% blue and black” in one moment and “gold and white…100%” in the next. Yet, there is more to this debate than color constancy and assumptions about light. For one, these factors do not appear to make much of an impact on those who see the dress as only blue/brown. For another, they do not tell us why some cannot see both white/gold and blue/black, despite trying the many different techniques. The remaining conflict probably comes down to either f) or some combination of a), b), and c). It is f) that I find the most interesting and which I think has been discussed the least.Here is the problem: most of us come into this debate first hearing that there are two options: white/gold or blue/black. Since the dress has neither white nor black in it, our willingness to side with one or the other camp may come down to the flexibility of our white and black color concepts. Some may have an inflexible white concept: In one video, the speaker “proves” that the dress is blue and black by selecting shades of blue and brown and arguing that shades from light to medium blue cannot be taken to be white (“it’s never white”), whereas shades from light brown to dark brown can be taken to be black (“it’s like a brown color. So I say it’s black”). Others may have an inflexible black concept: In my own experience of viewing the image, it is much more difficult for me to see the dress as blue and black than white and gold. But I have found that I often take items sold as black to be non-black (usually dark blue). Thus, I suspect that my concept of black is less flexible than for others. So different color concepts are likely playing a role. Yet, I don’t think there is one true cause of #dressgate. If anything, I think it is because so many factors involved and are so difficult to tease apart that this controversy has had so much purchase.

If you hold a burning hot pot, its energetic property causes activation of specific sense organs, and you feel a burn in your hand. Non-realist views on color (to roughly refer to a range of views) often imply that unlike the case of the pot, the experience of the energetic property of color is dependent on viewer and context, and is therefore unreliable. To use a distinction Garner makes in his book (1974): while energetic property does activate sense organs, “it is stimulus information or structure that provides meaning and is pertinent” to perception, where structure is understood as “a complex system considered from the point of view of the whole rather than of a single part”. In other words, it is precisely the relation of an object’s color to viewer and context – lighting and surrounding objects – that is relevant to our experience of the object’s color.The Dress episode straightforwardly shows that taken out of context, the energetic property of the color of the dress is literally meaningless. Perhaps this should encourage us, in our discussions on the nature of color, to consider it as having an informational property along with an energetic one.

If you hold a burning hot pot, its energetic property causes activation of specific sense organs, and you feel a burn in your hand. Non-realist views on color (to roughly refer to a range of views) often imply that unlike the case of the pot, the experience of the energetic property of color is dependent on viewer and context, and is therefore unreliable. To use a distinction Garner makes in his book (1974): while energetic property does activate sense organs, “it is stimulus information or structure that provides meaning and is pertinent” to perception, where structure is understood as “a complex system considered from the point of view of the whole rather than of a single part”. In other words, it is precisely the relation of an object’s color to viewer and context – lighting and surrounding objects – that is relevant to our experience of the object’s color.The Dress episode straightforwardly shows that taken out of context, the energetic property of the color of the dress is literally meaningless. Perhaps this should encourage us, in our discussions on the nature of color, to consider it as having an informational property along with an energetic one.

As far as weird colour phenomena go, this is one of the best I have seen. The way in which it went viral says something! I think what it shows is that most people do not realize that it is possible to have an ambiguous stimulus for colour – i.e., that it is possible for your brain to “colour” a scene before you differently if the scene can be relevantly interpreted in more than one way.

Most people are familiar with ambiguous stimuli for primary qualities like shape (Necker cube), size and even motion (the spinning dancer), but ambiguous stimuli for secondary qualities like colour are not really very common at all. (Am I wrong?) An old example was Mach’s corner, easily googled for those who don’t know this one. Depending on how you structure the ambiguous corner, a certain region can appear to be a lighter or a darker grey. This just concerns lightness (or brightness) and not hue. So the dress example is much better.

I also one saw a structure from a hotel window that could be “seen” as either a road or as a fence running along the edge of a field. (It was actually a road.) If you saw it as a road, it seemed to be black (and seemingly bathed in the sun), but if you saw it as a fence, it seemed to be white (and seemingly in the shade). Ambiguous stimulus for colour! These examples deserve to be better known.

One thing I haven’t really seen people comment on is the role of digital photography in generating this episode. Digital cameras also make guess about “whether that content should be assigned to the surface or the illuminant” and in this case the digital camera seems to have made a terrible guess because of the nature of the lighting. Part of what is happening in this case in some degree depends on the “broken telephone” phenomenon. The camera has made a guess based on the conditions in the world, and then our brains are making a guess based on what the camera has delivered. I’m guessing this plays some role in producing this image that is so close to a bifurcation point.

I also have yet to read anything that gives conclusive reasons in either direction concerning whether the effect is conditional on background knowledge or something more congenital. I wonder if experiments will be conducted to determine this. You would need experiment subjects who either had been asleep for the last week or were the unibomber.

Actually you just need to use a different picture.

There is small body of research that suggests that explicit belief about the illuminant does not play a significant role in color perception. The effect of memory color is also typically regarded as small and it’s hard to see how memory could make a difference here. Any variation in background knowledge that explains this case would also have to be such that it wouldn’t interfere with the very large number of cases in which people who disagree about this image see the color of images (or actual scenes) in the same way. So I don’t think it’s likely that explicit belief is playing a role here. That doesn’t mean thatthe variation is congenital since (to attempt a fairly neutral description) the operating parameters of the color vision system are constantly changing in ways that depend on past experience, varying physiological parameters, what else is currently perceived and more “cognitive” factors like attentional state.

1. In their commentary on the dress, Byrne and Hilbert note that people responded to a clear case of interpersonal variation in color appearance by (at least in part) displaying astonishment; and they seem to take this to indicate that ordinary people are not so accepting of interpersonal variations in color appearance as they profess to be.

I’m not at all sure how deeply and widely committed to such variations ordinary perceivers are — I certainly wouldn’t take such commitments to be dispositive about much.

However, and be that as it may, surely there’s an obvious understanding of the popular display of astonishment that is consistent with taking there to be a widespread committed to such variation. On the face of things, folks are simply and understandably astonished at the degree and persistence of difference revealed in the case at issue (which are indeed pretty astonishing). Given this interpretation, there’s no need to accuse the folk of bad faith.

2. On the other hand, B&H take it that the reactions we saw reflect (in part) “an intense commitment to knowing the real colors of things” (presumably, as opposed to merely apparent colors of things), and they recommend on this basis rejecting the claim that “color is subjective”.

Much depends here on what they mean by the latter claim. But I don’t see in the observation that folks are committed to knowing the real colors of things any compelling argument against (serious) views that would sustain it.

To see why, consider the traditional secondary quality view (one sometimes attributed to Locke) that colors are something like powers to affect normal perceivers in normal conditions. Plausibly that makes colors count as subjective in the good sense that their natures essentially incorporate subjects (of a certain kind). But, exactly because the subjects in whom color appearances occur can fail to be subjects of that stipulated kind, it is perfectly consistent with this subjectivist view of color that the appearances could fail to reveal/match/represent the real colors of things.

Much the same lesson holds, it seems to me, for other theories aiming to sustain the view that colors are subject-involving: these theories can reconcile the observed preferential interest in finding a distinguished and interpersonally stable description of the color of the dress with their subjectivism so long as it makes sense to say that we can be more interested in ONE of the subject-involving colors recognized by the theory than in others (for whatever reason — principled or otherwise). And, indeed, it does make sense for proponents of such theories to say just that: surely they can allow that we might be interested (for some purposes) in, say, the subject-involving color the dress manifests under an illuminant with a relatively flat spectral power distribution (say, something approximating noon daylight) rather than the subject-involving colors the dress manifests under an illuminant highly skewed in its spectral composition.

3. As far as I can see, then, there is nothing in the popular reactions to the dress that motivates rejecting views on which colors are subject-involving. This is, of course, not to say that we should therefore accept such views, and especially not that we should do so simply on the basis of observed reactions to the dress on social media.

Like everything I’ve read by Byrne and Hilbert, their piece leaves me with the impression that they are cynically generating controversy (and thus more papers!) by provocatively defending a position that’s believed by next to nobody, least of all themselves. Anyway, your piece on the dress controversy is the most succinct response I’ve seen, with the exception of the uncredited illustration by Akiyoshi Kitaoka at the top of this page.

I genuinely keep seeing this as blue and gold. I don’t know what must be wrong with me?!

I think it means simply that the visual stimulus is three-ways ambiguous, colour-wise. That’s possible in theory and quite believable in this particular case. Blue and gold may simply be a third “stable” way of “seeing” the dress.

P.S. This vine shows (more viscerally) how the thing can be colour-wise ambiguous. It looks white and gold up close, but when he pulls it back, it turns black and blue. A really good demo:

https://vine.co/v/O2rvPnlEzqi

Perhaps you can find the blue and gold somewhere in there too Filippo.

Thanks, Jack! It’d be neat if it were a three-way ambiguity issue, and the Vine you linked to suggests that explicitly. As to myself, I see the blue and gold and the white and gold in that Vine, though not the blue and black. But at least I’m not a _complete_ freak of nature.

My brain thinks your brains have no clue what’s interesting about the dress. How long have scientists’ brains known about color constancy? And nobody’s brain ever thought to make a picture that half the world’s brains would judge a different color from the other half? My brain sees a lot of “explanations” of the dress, but it doesn’t see another picture that accomplishes what the dress picture accomplished. Make a picture that half the world’s brains see as yellow, the other half purple. Quit showing my brain pictures whose (apparent) color everybody’s brain agrees to. C’mon brains, predict…manipuate…until then, my brain is unimpressed with these “explanations”. Here’s a hint, from my brain to yours: A brain that has property B1 will judge a picture with property P to have color C1; whereas A brain with property B2 will judge a picture with property P to have color C2…where judgements are made from within the skulls of bodies in the same lighting conditions, and where the presences of B1 and B2 are confirmable independently of color judgments. Is that too much to ask?