Many thanks to John Schwenkler for this opportunity to talk about some of my recent work, especially my book The Centered Mind: What the Science of Working Memory Shows Us About the Nature of Human Thought, published earlier this year by Oxford University Press. In this post I’ll sketch the theory that I defend in the book, and then in subsequent posts I’ll talk a bit about some of the component ideas.

The goal of the book is to develop a theory of the causes and contents of reflective thinking, and indeed of the stream of consciousness more generally. The basic thesis is that all access-conscious mental states are sensory based, in that their conscious status constitutively depends upon some or other set of content-related sensory components (that is, mental images in one sense-modality or another). I argue that amodal concepts can be bound into the content of these access-conscious images, however. Thus one doesn’t just imagine colors and shapes, but a palm tree on a golden beach, for example. Here the concepts palm tree, golden, and beach are bound into the visual image in the same way (and resulting from the same sorts of interactive back-and-forth processing) as they are when one sees a scene as containing a palm tree on a golden beach. But the access-conscious status of these concepts is dependent on the presence of the sensory components into which they are bound.

I’ll talk more about the role of attention in all this tomorrow. But for the moment the key reason why all contents in the stream of consciousness are sensory based is that access-consciousness should be equated with global broadcasting in the brain, and because attentional signals directed at mid-level sensory areas are a necessary condition for global broadcasting to take place. So the only way for an amodal concept or thought to become access-conscious is by being bound into a sensory object-file or event-file and globally broadcast along with it.

(I argue at some length that there really are such things as amodal concepts and propositional attitudes, and I reject so-called “sensorimotor” theories of cognition.)

The stream of consciousness results when attention is directed at endogenously-activated sensory-based representations, often working together with conceptual cues of one sort or another, as when one struggles to recall an acquaintance’s face, or follows a command to imagine a green dragon. In such cases conceptual cues activate related sensory representations in mid-level sensory regions of the brain, which then become targets of attention, resulting in globally broadcast object-files into which representations of both sorts are bound. But another way in which contents can be created is through mental rehearsal of action (especially speech action). In such cases an activated motor plan is used to construct a sensory forward-model of what one would experience if the action were executed (while instructions to the muscles are suppressed). When attended to, these sensory representations are globally broadcast in the normal way. Hence an athlete might feel herself, proprioceptively, making jumping movements while she mentally rehearses the high-jump she is about to perform. And likewise we hear ourselves saying things, in inner speech.

In addition, I argue that the contents of the stream of consciousness are all actively produced. They result either from mental rehearsals of action or from shifts in the direction of top–down attention (which is likewise under intentional control). Changes to the contents of the stream of consciousness result from unconscious decisions, either to rehearse one utterance (or other form of action) rather than another, or to direct attentional signals toward one representation rather than another, or both. Sometimes these decisions result from goals we know about, such as complying with a prior request to imagine a green dragon. In these cases we experience the stream of consciousness as under our control, and we take ourselves to be actively engaging in reflection. But often decisions are taken for reasons that are obscure to us. In such cases we experience the stream of consciousness passively. We say that we merely find ourselves thinking about something new, often in ways that we say are “against our will”. But in reality these cases are just as much actively controlled. The distinction that many people draw between active and passive forms of imagination is merely epistemic. The underlying processes are the same.

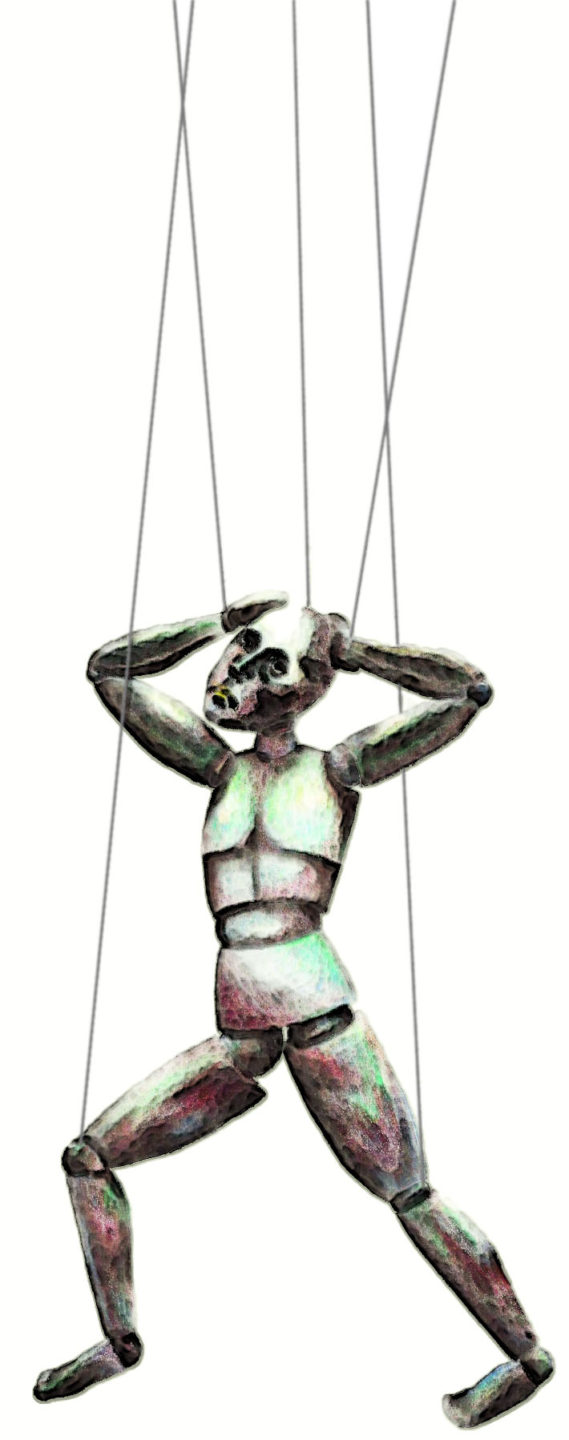

I argue that the stream of consciousness never itself contains amodal judgments, decisions, goals, or intentions. Rather, these mental states do their work unconsciously, influencing decisions about which sentences to rehearse, and how to direct attention. The bottom line is summed up in the subtitle of the concluding chapter of the book: The conscious mind as marionette. For a brief informal presentation of the implications these ideas for our self-conception, see my earlier post on the OUP Blog at:

Hi Peter,

I have been looking forward to your book since your August piece @ OUP, and am grateful for this post as spur to get a copy.

My own conscious life diverges somewhat from that which you describe above, though in a way I hope your theory may illuminate.

It is, to use the newly minted term, “aphantasic”. The only purely sensory-based representations I get endogenous conscious access to are verbal, i.e. absolutely no taste, touch, smell, or visual or non-verbal auditory images — though I do know what the latter two are like from the (rare) dream.

While I never experience the component sensory contents, I do have access to the bound amodal concepts you suggest are dependent on them. Or at least — I take myself to. There’s a conscious difference between each successive imagining of the dragons Smaug and Puff, though not a sensory one. (Having just cycled through them, in the former case there was what I can only describe as a conscious expectation of sharp claws — but it loses fidelity in description). There’s an even clearer difference between imagining a green dragon and my e-mail inbox, and it would likely register in a skin conductance test.

Would your theory just rule out the possibility of my unbound amodal contents, predict that my attention would read out in a scan as deviantly not mid-level, or something else entirely?

Thanks!

Wilder

In general I don’t think introspection is to be trusted. (See my previous book, The Opacity of Mind.) But first a question: do you claim an incapacity for tactile and olfactory imagery, or are you just saying that such imagery doesn’t occur spontaneously? If the former, then you should be incapable of comparing one stroke on the arm with another a few seconds later (which would require sustaining a working memory representation of the way the first touch felt). I am not aware of such deficits in the absence of sensory-specific brain-damage.

On my view the sensory representations needed to support a working memory conceptual representation need not be highly specific. This is especially true when one is aware of setting oneself to conceive of e.g. Smaug. Given this context, even minimally dragon-like sensory representations may get interpreted as a representation of Smaug, with the latter concept getting bound into them. My best guess is that something like this is going on in your case. You don’t report sensory representations because no such representations seem especially relevant to the conceptual contents you report, not because they aren’t present.

But to answer your question directly: yes, the theory rules out the possibility of unbound but globally broadcast conceptual contents.

Thanks for the reply.

Having spent a life quizzing friends on the features of their imagery, I am with you completely on the unreliability front.

To your question about tactile / olfactory images, by ‘spontaneously’ I take you to mean internally generated, intentional or otherwise, but not exogenous — in which case it’s an accurate description.

In the case of the stroke test I can tell which of two was longer, but it doesn’t feel *at all* as if I’m mentally comparing two sensory representations. Subjectively, I take the measure of the first as it happens, and compare it to the measure of the second as it happens. And I really wouldn’t know how else to tackle it!

What you say about the limited specificity/saliency requirement to bind concepts is very interesting and seems likely.

Hi Peter,

I recently finished reading ‘The Centered Mind’. I thoroughly enjoyed it – you’ve done a wonderful job synthesizing the empirical data.

I do have one question, however. On your view, although amodal conceptual information can’t be globally broadcast by itself, it can nonetheless be bound into sensory representations and get broadcast along with the latter. I’d be interested to know what you think this binding process amounts to: How exactly does amodal conceptual information get bound into sensory representations?

If you have any suggestions for further reading I would really appreciate it.

Thank you!

Max

Max,

That is a great question, and I wish I knew the answer! The problem is that we don’t yet have a fully worked out theory of binding in general. As is familiar, different aspects of a visual stimulus are processed in different regions of visual cortex. Yet all can nevertheless be experienced as bound together in one object or event. One popular view is that neural synchrony is an important part of the explanation. Then amodal information activated by an incoming sensory signal, say, would get bound into that signal when the neurons that encode the amodal component are entrained to fire synchonously with the sensory component, and then (when the latter is targeted by attentional signals) it would get made globally available along with it.

Here are a couple of reviews of the binding problem(s), which also emphasize some of the complexities:

Treisman A (1999) Solutions to the binding problem: progress

through controversy and convergence. Neuron 24:105–125

Velik R (2010) From single neuron-firing to consciousness–towards the true solution of the binding problem. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 34:993–1001

best

Peter

Hi Peter,

Thanks for getting back to me. Your response was very helpful.

I have a quick follow-up question:

One of the things you say in your book – in support of such binding – is that there are interconnections between mid-level visual areas and regions of association cortex (which presumably store conceptual information). This leads you to conclude that “information from conceptual regions is projected back to earlier stages of processing, influencing the latter, and becoming a component in the perceptual state that follows visual recognition” (p. 66).

This strikes me as somewhat different from the neural synchrony view. You seem to be suggesting that binding (of amodal information to sensory representations) is achieved via some sort of top-down causal process.

Please correct if I’ve gone wrong here! I’m just trying to get a handle on your view.

Max

Max

There are two processes / stages involved (albeit temporally smeared and interactive ones). One is the processes involved in visual recognition – identifying something as a cat, a dog, a bird, or whatever. This is done by top-down “querying” of lower-level representations and a sort of inference to the best explanation of those representations. Then there is whatever process binds the winning concepts into the sensory representations that they conceptualize.

best

Peter

Ok – that clears up my confusion. Thanks again for your help.

Max