Knowing is a state of mind that can’t be wrong. If anyone knows that p, then p must be the case. My last post raised the question of why adults attribute that state of mind so heavily, in their ordinary descriptions and explanations of agency, rather than relying on what might seem like the more economical state of belief for all transactions, marking them as true (or false) as needed.I mentioned a potential partial explanation in the relative ease of thinking of knowledge rather than belief: because only the real can be known, no extra resources have to be added to represent what is in the domain of a knowledge attribution. Whether we are looking at winners or losers, even being in the game of knowledge attribution seems to restrict us to truth, as we see from the factivity of “knows”, in the linguist’s strong sense of “factivity”. We presuppose the truth of the complement (=what follows the “knows that…”), even when reasoning hypothetically, in the antecedent of a conditional, or placing it under a modal (like “perhaps”), or under ordinary sentential negation.

One can either use a “that-” clause after a factive verb to go ahead and pick out some state of affairs that is already part of one’s take on the world, or one can use a “wh-” clause to denote just the true answer to some question one has in mind (“He knows what is on the other side of that wall”). Nonfactive verbs like “think”, by contrast, open up a much wider domain from which contents might be selected.

When we reflect on situations where knowledge is ordinarily attributed, however, we can wonder why we don’t always go hunting in that much larger domain. In a control version of the unexpected transfer task, where our agent looks away, and then comes back, but nothing funny has happened, we treat him as still knowing that the ball is hidden in the initial basket. From his perspective, however, things appear just as they would if someone had moved that ball (hello sticklers, I’m assuming a lid on the basket, and on the box). How does he count as knowing? Why doesn’t he just count as having a true belief?

Versions of this problem (in different guises) have been posed by Gil Harman and refined by Jonathan Vogel. I’ve dubbed this the Harman-Vogel paradox, although I feel guilty about not dubbing it the Dretske-Harman-Vogel paradox because the late great Fred Dretske had the original idea behind it. In the classic version, someone (call him Al) has parked his car on Avenue A (out of sight now) half an hour ago. Everything is normal, the car is still there, Al has a good memory. Does he know where his car is? Sure. (If you doubt that we’d naturally use the verb “know” here, just spend a little time in a good corpus looking at natural usage. You’re welcome.)

But let’s make things harder now. Every day, a certain percentage of cars gets stolen. Does Al know, right now, that his car has not been stolen and driven away since he parked it?

Suddenly it’s harder to answer in the affirmative. And notice: if his car is still there, then it follows logically that it hasn’t been stolen and driven away. If he can know that his car is on Avenue A, why can’t he just deduce that it hasn’t been stolen? Sound deduction should be a rock solid way to extend your knowledge, why is it failing us now?

Meanwhile, in a parallel universe with a similar crime rate, Betty has parked her car on Avenue B half an hour ago. Betty is cognitively very similar to Al (just as good a memory, just as much confidence about the location of her car). Her car, unfortunately, was stolen and driven away. Clearly Betty, who believes that her car is on Avenue B where she parked it, doesn’t know that her car is on Avenue B. But everything relevant appears to Betty the way it appears to Al (okay, changing the letter of the alphabet). Think about Betty long enough and you’ll find yourself wondering whether you know where anything (that you aren’t presently watching) is located. You are opening up for yourself that larger space of possibilities, a space that goes much beyond the economical (“my car is in my driveway and my toaster is on my kitchen counter”) space that you ordinarily work with. Imagine a silent toaster thief who has just… . No really, be a sport, try to imagine that. If you can actually make yourself do it, vividly enough, then you are such a nerd. But also, you can make yourself feel like “know” is the wrong word to use for the location of your toaster. (Or maybe what you now feel you know is something weaker than “it’s on the counter” — maybe you just know “it’s very likely on the counter”, or, as Igor Douven proposes here, “it’s on the counter, assuming nothing highly unusual has happened.”)

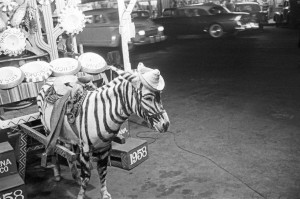

My line on this is that something changes in our thinking when we switch up from answering an “easy” question (where’s your car? what is that black and white-striped animal?) to answering a harder one (do you know your car hasn’t been stolen in the last half hour? do you know that this animal is not a cleverly disguised mule?). The hard questions, we have noticed, require contemplation and then negation of a possibility represented in that larger field we don’t usually reach for. And the crucial ones in the Harman-Vogel paradox reach for possibilities that we’re going to have trouble finding consciously available evidence to rule out. Who is the President of the USA? (easy question!) Do you know that Barack Obama has not died of a heart attack in the last five minutes? (hard question!) We switch from making judgments without first-person awareness of any stages of reasoning (Type 1 thinking, if you will) to making judgments in a manner which crucially depends on conscious thought (Type 2). When we switch over to conscious thought, the best we can do with what is available to us consciously (in these particular Harman-Vogel cases, which are designed to hit gaps in our armor) is reach a guarded answer about probabilities: when the bad car-theft scenario is in mind, the plain old categorical judgment (of course my car is still there!) is not something that we can reach without bad reasoning (and bad reasoning always sours one’s entitlement to knowledge attribution).

Notice also that when you start thinking about the hard question you lose the ability to make your ordinary naive judgment about the easy question (until you can get that problematic possibility to fade from working memory). You temporarily lose the capacity to make your typical knowledgeable judgment (and notice that explicit deduction is a paradigmatic Type 2 process, and needs to proceed from knowledgeable judgments if it is to issue in knowledge).

I’m happy to insist that our ordinary naive judgment does constitute knowledge, and to extract the lesson that one may know things even in cases where, if one were to reflect on all the things that could be going wrong, one might lose confidence, have doubts, and lose either the knowledge itself or more minimally, the current power to access it. I don’t think there’s any good reason to restrict knowledge to what the subject can defend by appeal to evidence that is consciously available to her, although I’ll grant that we can easily start to get the feeling that we should think of knowledge that way. I’ve been wondering about the step up to conscious thought, and whether our feelings about what’s acceptable there are really driven by something like the need to persuade others, as Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber have suggested. This might explain why Al looks bad after we start thinking about Betty.

You might protest that my exercise with the toaster was just a story about what happens in the first person, and we can stipulate that Al isn’t having any doubts that he is rashly dismissing. Interestingly, although this is originally a first-person phenomenon, other people’s claims to knowledge start looking bad to us when we open up that larger domain of possibilities for ourselves, even if we stipulate that they aren’t thinking about the larger field, and even if we stipulate that they really are getting it right. Al, thinking naively, is right when he says that his car is on Avenue A — but keep toggling your mind over to Betty’s predicament, and he looks bad.

I’ve experimented with a few different explanations of what’s going on here. I still somewhat like the idea that we are struggling here with the deepest bias of mental state attribution, and projecting our frame of mind onto others even while well aware that they don’t share our concerns. Notice that Al should be represented as more naive than we are (once we’ve thought about Betty), and we systematically misrepresent the perspective of more naive thinkers (even when we have incentives not to, and with little insight into how we are doing this). I’ve since had some second thoughts about that explanation, and wondered whether the phenomenon is really driven by more general mechanisms that regulate the extent of evidence search. I started working that answer out here, but I’ve been trying to push it further since learning more about those mechanisms.

There’s a longer story to tell but I don’t want to be a blog hog, so I’ll close by taking us back to Gettier cases. Thinking about Betty and Al may have left you with the impression that you should be more stringent in your knowledge attributions. You might feel that Al shouldn’t be counted as knowing because things look to him much the way they look to ignorant Betty. If we want to say that Al knows, we have to give up the idea that Al has to be able to prove to everyone’s satisfaction that he is not in a Betty-type situation. Knowing is a matter of his relationship to reality: he has to be thinking in a way that is nailing the truth, in a manner that is appropriate for the actual environment in which he finds himself. Because his environment is friendlier than Betty’s (his car is safely where he left it), objectively, there is no reason for him to double-check the location of his car before saying where it is: a naive judgment is good enough there.

Or that’s what I think. If the Al-Betty comparison has made you feel uneasy about your knowledge of presently unwatched objects, let’s talk about the objects we are watching now, also. Suppose you see an agent who is looking right at something. He knows it’s there, right?

Our counterexample will come from my favourite 8th-century epistemologist, Dharmottara. Arguing against a proposed analysis of knowledge as “the state of mind that underlies successful action”, Dharmottara asks you to imagine a desert traveler in search of water. It is hot, and as the thirsty nomad reaches the top of a hill, he is delighted to see a shimmering blue expanse in the valley ahead — water at last! He rushes down the into the valley. Actually, the story goes, what our man saw was a mirage. But the twist–there’s always a twist–is that there actually was water in the valley at just the spot where the mirage led him. Successful action! But did our nomad have knowledge, as he stood on the hilltop hallucinating? Surely not, suggests Dharmottara, scoring a decisive blow against the epistemology of Dharmarkirti. [The story is from the Explanation of the Ascertainment of Valid Cognition D:4229, 9a2-3, as told by Georges Drefyus on p.292 of this great book.]

It’s a Gettier case, right? (Assuming, charitably in the context, that our nomad’s hallucination was very realistic, and he had no reason to doubt his senses.) Jonathan Stoltz expresses reservations about applying that label here, because Dharmottara himself has an infallibilist conception of justification, and, as he rightly notes, regular participants in the Gettier Analysis of Knowledge Program need to work with a fallibilist conception of justification. It must be possible for you to have a justified false belief — if justification already ensures the truth of your belief, your conception of justification is too strong (see the collected works of Stephen Hetherington on this point). I’m going to agree with Stoltz that Dharmottara would not have been on the regular Analysis-of-Knowledge bandwagon (that’s part of what makes him my very favorite 8th-century epistemologist). Still, you can find that a certain type of case works wonders for criticizing other people’s efforts to analyze knowledge reductively, even when you aren’t peddling any reductive analysis of your own. People like Tim Williamson (and me) should still get to help themselves to the handy category “Gettier case”, not least to criticize fallibilist conceptions of justification (so I’ll resist Stoltz on this point).

Back to the case. The nomad is looking right at the water, declaring “there’s water!” and, let’s say, everything in his inner subjective landscape perfectly matches what is outside him — let’s say by chance he has a perfectly veridical hallucination. But he doesn’t know that there is water there in front of him. And we can always wonder, even in the case where Smith is looking right down at the ball in the basket (now with the lid removed), and saying, “there’s a ball”, whether it just might be possible that Smith is right now merely having a veridical hallucination as of a ball, and basing his judgment on that. Looking at Smith from the outside, on an ordinary day, how do we know that he knows? Or what is it, precisely, that we are so readily attributing to him when we call up that extremely common verb to describe his relationship to the location of the ball?

Especially when it’s late at night, when I face questions like that, I have to keep my guard up and fight against the temptation of trying to formulate some kind of analysis of knowledge that would break it down into being a certain type of belief with special features added. I actually think part of that temptation comes from the general arena I wandered into in this last post: the realm of conscious thought. When we think about our own epistemic relationship to any random proposition we’d ordinarily take ourselves as knowing, it’s very natural to open up the wider field of other ways the world could be, and very easy to find ourselves in a position where we are ill-equipped to defend that proposition argumentatively. I’m quite sure that argumentative defense isn’t the only way that propositions are intuitively registered as known by agents. And, forcing myself to think reflectively and systematically about knowledge, I think our naive intuitions are right on this point: there is no good reason to deny that we often have plain perceptual knowledge (and knowledge from inference and testimony, too). But we can easily get ourselves in a reflective frame of mind where things start seeming otherwise. One possible line of defense against these illusions (to which reason is naturally prone!) is to study them, now with the resources of various other disciplines at our side as well. Building a better theory of the relationship between intuitive impressions of knowledge and knowledge itself will be an enormous chore. And, you know, not the kind of thing one could dash off in a blog post (sorry!).