In my previous post I set up the problem of how to interpret the uses of psychological predicates in many unexpected domains throughout biology. In this one I will describe in general the evidence on which the extensions are based. I divide this evidence into two types: qualitative analogy and quantitative analogy. (Any case of extension can include both.) Qualitative analogy is familiar from the history of science – e.g., the mini-solar-system model of the atom – and, in biology, evolutionary lineages that yield homologies (or homoplasies, if the same functions develop in distinct lineages). Much of the evidence for the new extensions so far is of this sort.

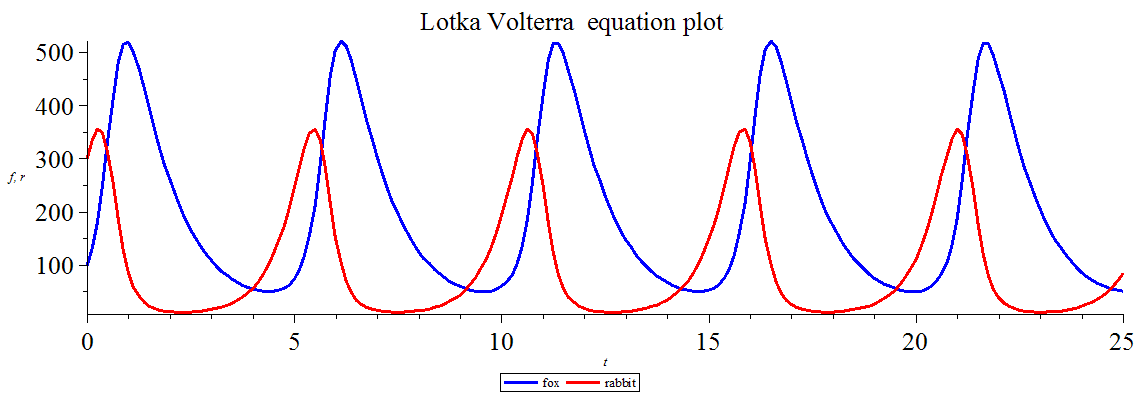

The more interesting type is quantitative analogy, or extension based on mathematical modeling. A non-psychological example of a mathematical model is the Lotka-Volterra model, which captures the fluctuations in relative size between predator and prey populations. Following Weisberg, a model consists of a structure (in this case, described by two linked equations) and an interpretation or construal, which specifies what the modeler intends the symbols in the equation to stand for (in this case, real-world populations of sharks and cod (or other prey fish) in the Adriatic). The crucial fact about models in this context is that scientists try to extend them to new domains all the time, and it is not up to them whether the data gathered in the new domain will fit the model or not, setting aside questionable data-massaging. For example, the Lotka-Volterra model has been extended to the relations between foxes and rabbits, wages and jobs, and capillary tips and chemoattractant, inter alia. This is important because scientists are using mathematical models of cognitive capacities in new domains and extending the concepts used in the construals to the new domains. It is not up to us whether a model fits in the new domain. But if it does, that provides strong, if prima facie, evidence that the entities in the new domain possess the capacity being modeled. Moreover, that evidence is objective in the sense that it is independent of ordinary observation-based judgments of the entities’ similarity to us. A model provides at least structural similarity between distinct domains and motivates inquiry into the nature and depth of the similarity.

An example is Roger Ratcliff’s Drift-Diffusion Model (DDM) of two-choice decision-making, which was initially developed from data gathered from people (e.g., college undergraduates). These are simple choices, such as deciding whether a given stimulus is the same or different from a sample, and then pressing a computer key “yes” or “no”. (In real life: (e.g.) should I go to the left or the right around this obstacle?) The model divides the time from the presentation of the stimulus to the subject’s response into a non-decision time (encoding the stimulus, preparing to press the key) and the decision time, which includes the cognitive processes of accumulating and assessing evidence until a decision threshold is reached, and then making the decision. The model captures the speed-accuracy tradeoff whereby, when presented with noisy stimuli, we make either quick or accurate decisions but not both. It turns out that the model also applies to fruit flies (inter alia). In fact, differences in the speed and accuracy of fruit fly decision-making have been linked to mutations in the FOX-P genetic family, which is linked to cognitive deficits in humans.

To make the problem vivid in non-technical form, I’ll modify a popular version of the Argument for Other Minds:

(Original Argument)

- My behavior is caused by my mental states.

- I observe that others behave similarly to me.

- Either they have mental states that cause their behavior, or I am unique and something else causes their behavior.

- The first hypothesis is best because it explains both cases.

- So it is probable (or rational to conclude) that they also have mental states.

(Modified Argument)

- My choosing behavior is caused by my decision-making processes.

- Scientists have developed a quantitative model of decision-making of my and others’ choosing behavior.

- Either the models’ construals are the same for others or I am unique and we must interpret the construals differently for the others.

- The first hypothesis is best because it explains both (or all) cases.

- So it is probable (or rational to conclude) that they also have decision-making processes.

Anyone who accepts the original argument should find the modified version cogent as well. It just so happens that the “others” includes fruit flies, inter who knows how many alia. (Volterra started with fish, after all.) Nothing has changed except for the entity to which the capacity is ascribed. To point out that the new entities are non-human merely raises the question: What determines whether the capacities ascribed to the entities are real or full-blooded?

Your modified argument, as well as the original, are philosophically rather weak.

A human being can volitionally, or voluntarily, choose to act or to not act, in many ways (I have no qualms in believing this to be also true of fruit flies, and some or all other living beings). In others words, the act they perform, is not caused; not by neurological activity, nor by mental states. [cf. Bennett and Hacker (2003) p.228-31]

They can choose to act on the result given by some decision-making process, be that a volitional mental calculation, or simply tossing a coin. But the decision-making process does not cause them to act, because they can equally choose not to act on that result. But of course tossing a coin does determine, through a causal process, the result of the decision-making process.

An example where this distinction is useful is with the “smart amoebas” presentation.

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn15068-smart-amoebas-reveal-origins-of-primitive-intelligence

I have no objection in principle to agreeing that the amoebae might be voluntarily taking decisions “to anticipate cold spikes”, and conversely not to, when the spikes cease. Whether they are or not, depends on whether we have good reason to consider them volitional beings, or mere automata, which I would not comment on.

However I do in principle object to the notion that memristors take such decisions, since they are not volitional beings, they are mechanisms that are built to perform in the way they do. Titanium dioxide has no choice but to act in the way that it does.

We can build mechanisms that model living beings’ volitional mental calculation, for example an electro-mechanical computer that performs basic addition. But the computer, providing it functions correctly in the way it is built to (and has no bugs), cannot itself choose to perform the calculation, or not to; it must. A person might.

Tony,

Thank you for your comments. You make a number of distinct points, some of which I agree with. For example, I haven’t argued that memristors (or titanium oxide, or other devices or commodities) have mental states — I’ve confined myself to biological creatures (but not just familiar fauna) and evidence we have for those extensions. We can and do also extend terms in other ways, and to non-living entities. It’s a big step forward, on my view, if we can understand how the terms can make sense (pace Bennett and Hacker) for these cases, and I will be considering non-living cases in future work. For the record, I discuss B&H at length in the book (their “nonsense” view): in brief, they do not consider the relevant evidence (they focus on popular-science presentations of neuroscience) and because of this they miss the fact that we have the kind of evidence that they explicitly agree would show that brains make decisions (to limit myself to their target case) — namely, mathematical models (e.g. of decision-making). As for further points:

(1) While decisions may not immediately yield action, the DDM does not claim that they do. It is a means by which we can capture empirically the making of a decision and some of the processes leading up to it. You seem to be saying that unless one can decide (i.e. “choose”) not to act after making a decision to act, one has not made a decision at all – i.e. in order to really decide to act, one must also decide whether to act on that decision to act. Where would that regress stop? Alternatively, you might be gesturing at the idea that we have free will (and memristors don’t, for example – we are “volitional beings” and they aren’t), and that where there is no free will there is no decision-making. Since whether we have free will in the libertarian sense is debatable, it follows on that view that whether humans really make decisions is also debatable. On a compatibilist view of freedom, of course, it just means there can be other causal factors between the decision and the act – and no one denies this. The DDM includes these in the non-decision processes that occur before and after the decision-making component of the RT.

(2) The ‘arguments from other minds’ are intended to present readers with a philosophically familiar way to think about mental-state ascriptions to others. Obviously if you find the original argument weak you’ll find the modified version weak. That is fine with me, actually – I’m not trying to argue against solipsism. The idea is rather that if you think the original is cogent, then you have no good reason not to accept the modified version. At least, there is a clear need to offer such a good reason, and in particular to offer one that does not beg the question against the Literalist.

Thanks for your response, Carrie.

To clarify, I haven’t argued that memristors etc, _do not_ have mental states (nor that they _do_). You seem to read it that I have. I am arguing that memristors do not choose to act. Amoebae – if they are volitional beings – choose to act; but if they are mere automata – they do not choose to act (which one it is, I wouldn’t profess to know). But with both volitional beings and non-volitional mechanisms there may be decision-making processes.

Only the former choose to act, though.

A volitional act – in your terms a “choosing behaviour” – is not caused by the decision-making processes, even if there are any. It is chosen by the volitional being (“choosing behaviour” is grammatically incorrect, the term should be “chosen behaviour” – there is no behaviour that does the choosing – the volitional being does the choosing). ISTM much of your project is underpinned by the notion that a volitional act is caused by decision-making processes.

This is the confusion that bewildered Libet (I referenced Bennett/Hacker’s response to his experiment, above). Libet’s experiments did show that conscious urges or decision-making cannot cause voluntary acts. They either come too early, like choosing to go to the cinema tomorrow; or too late as in his experiment. Libet’s confusion was to then conclude that the “[b]rain initiates [the] voluntary act unconsciously”. [Libet “Do We Have Free Will?”]

But instead, we should conclude that we, not our brains, initiate voluntary acts; not by causing them with decision-making processes, but just by getting on and doing stuff; often without thinking; without decision-making. The voluntary act begins (“initiates” – verb; intransitive) with brain activity. Indeed if I voluntarily move my arm, even without thinking about it, I’d be rather worried if it did not commence with brain activity. But the brain does not initiate (verb; transitive) the act.

So of course I can choose to not act on a decision even after I’ve made that decision, such as to go to the cinema tonight. In fact Libet’s experiment does show that, even after we’ve initiated a decision to act, and the neuronal activity has begun, there is still a small window of about 200ms after we are consciously aware of having initiated that decision, when we can reverse it. So we can actually initiate a decision not to act, even after we have initiated a decision to act; without there being a regress (I doubt there is time for any more reversals in the one act, certainly not infinite).

I feel the grammatical nexus of “to decide” is wider than you are granting; it’s not always synonymous with “to choose”. I think it fair to say that mechanical computers instantiate decision-making processes, and we can model that in program languages – “if… then … else … endif”. But computers don’t make the decisions. That is the job of the software/hardware designers.

Computers take the decisions, I can’t see who else does – not the designers who may be long gone. But they don’t decide which to take, in the sense of “choose”; they have no choice. The situation with brains and decisions/choices will I feel run along these lines, though to another level of complexity I’m sure.

I think Tony Wagstaff’s observations make a lot of sense. I’m also not convinced by the claim you make, Carrie, that Hacker and Bennett “miss the fact that we have the kind of evidence that they explicitly agree would show that brains make decisions.” I think they would explicitly disagree and I think they would refer back to the fundamental mereological principle that the parts that enable a decision maker to make decisions cannot themselves be decision makers.

At the end of your previous post you say:

“The current restriction to biology is empirical, not conceptual or logical, and may well be temporary given significant advances in artificial intelligence.”

Consider the question “Who (or what) stands to benefit from a certain behaviour?” The evolutionary development of the parts and internal functions of organisms is constrained by significantly different factors from those that pertain at the species level. In particular, inter and intra-species competition is obviously non-existent at the intra-organismic level. In other words, the parts of an organism are not in evolutionary competition with one another and therefore no exploitative alliances amongst them can benefit the organism as a whole. The startling corollary is that communication (and everything that goes with it from representation to intelligence) is a strictly species-level attribute because it is the product of exploitative alliances between organisms, which are to the benefit of the species as a whole whilst being to the detriment of its weaker members. This should be conceptual bedrock. When it is violated–and your book seems to inadvertently exemplify and document the worrying extent of the transgressions at large in scientific and philosophical discourse–we find species-level predicates being applied where they simply are not warranted by evolutionary science (or ordinary grammar for that matter). This should be a matter of central concern to anyone interested in the philosophy of mind or cognitive neuroscience. AI never does anything for itself, let alone for its species.

Thank you both for your comments. (I have been traveling, and am still.) I will do what I can to respond to the extent I can here, but I refer you to the book, where the discussion of Bennett and Hacker and the mereological fallacy is much longer and more nuanced. It’s a challenge to respond to assertions of what decision-making (or choosing or volitionally acting) requires because, well, they are just assertions; for current purposes, what’s important is that as such they almost certainly beg the question against the Literalist. They certainly beg the question if they build into decision-making tout court (or “choosing” or “willing” or what have you) assumptions that derive from intuitions about human decision-making (etc.), and even then certain kinds of decisions. So do memristors choose? The first step to answering this question, and this is the focus of the book, is to ask: How do we determine what it is to choose? Do we rely on what’s familiar to us, or do we have better sources of evidence that might contradict what’s familiar to us? I’ve argued for the latter. I haven’t argued for a specific definition of “to decide”, “to choose”, “to act voluntarily” and so forth.

Bennett and Hacker are quite clear (in their exchanges with Dennett and Searle, in Neuroscience and Philosophy: Mind, Brain, and Language) about the sort of evidence that might show that brains really have cognitive properties; they just don’t think that sort of evidence is or will ever be available, and in this (as I argue in the book) they are wrong. Furthermore, and I also argue this at length in the book, the so-called mereological fallacy isn’t a fallacy – I suspect it arises by taking compositional principles that appear to hold for objects and extending them, mistakenly, to activities. Elliot Sober also pointed this out long ago. Planets and atomic nuclei both rotate (to use his example, though the point is quite general) – a planet doesn’t (and, maybe, cannot) have planets as parts, but there’s nothing wrong with a planet rotating and its parts rotating. (I’m well aware of homuncular functionalism, and that’s another mistaken theory I deal with in the book.)

I don’t think Bennett and Hacker are wrong in complaining that neuroscientists have often played fast and loose with psychological predicates in their popular-science writings. I’ve written on this problem (separately) myself. But that is quite a different problem from the issue of how science is modifying the extensions of psychological predicates.

Finally, I’m glad to see the comment about what “ought to be conceptual bedrock”, because on the Literalist view the bedrock is shifting, like tectonic plates. Even if there is no evolutionary competition between parts of an organism (at least grant this is so), I fail to see why this should be a constraint on what a psychological predicate refers to. What the argument for that view? Recent work on signaling systems applies to signaling between parts of organisms and between organisms – e.g., work by Skyrms, Shea, Cao, Godfrey-Smith and others – so simply asserting that communication is only at the organism level (for evolutionary or other reasons) doesn’t get one very far – although it does seem to have taken us far from the topic of the book.

Thanks Carrie, – there’s no rush BTW! On which I’m afraid I can’t comment directly on your book as it’s not yet in print in the UK. My comments are directed to your posts on this site.

You say the “focus of the book, is to ask: How do we determine what it is to choose? ” Now this is question begging, since one needs to have determined what it is to choose before we can even ask the question; we need some understanding of “what it is to choose” for the question to make any sense. Einstein did not set out to determine what space/time is; he set out to explain the evidence we have, e.g. the results of Michelson Morley’s experiments. He did so, not with evidence as to what space/time is, but Gedankenexperiment. He thought it up – he didn’t discover it. His explanation had to make sense (to many it doesn’t on first encounter). And it needs to make sense of the evidence.

The same with “to choose”. We make language up as we go along. It needs to make sense of the evidence, but it also needs make sense in and of itself. Wittgenstein is appropriate for your account – and also with Libet “How does the philosophical problem about mental processes and states and about behaviourism arise?——The first step is the one that altogether escapes notice. We talk of processes and states and leave their nature undecided. Sometime perhaps we shall know more about them—we think. But that is just what commits us to a particular way of looking at the matter. For we have a definite concept of what it means to learn to know a process better. (The decisive movement in the conjuring trick has been made, and it was the very one that we thought quite innocent.)—And now the analogy which was to make us understand our thoughts falls to pieces. So we have to deny the yet uncomprehended process in the yet unexplored medium. And now it looks as if we had denied mental processes. And naturally we don’t want to deny them.” [Philosophical Investigations §308]

Libet left it undecided as to whether we have “free will”, but his naive conception as to how we might find out – the conception he had that a felt urge or desire was a necessary causal factor in volitional behaviour (one which you seem to hold to) simply leads to a paradox where he denies free will, and instead our brain decides things for us, except when we want to override what it is the brain has decided upon, then magically our free will is restored. This paradox is removed if we have a sensible well thought through notion of free will before we interpret the evidence, as I’ve outlined above.

You are under the same misconception:- that “choosing [sic] behaviour is caused by my decision-making processes”. We may dismiss “choosing” as poorly worded, though why would we then trust the judgement of someone as to “what it is to choose”, when they are clearly struggling with its basic grammar? When they don’t know their way around as Wittgenstein might put it.

But we can also take this as the “decisive movement in the conjuring trick”. By committing to this dubious grammar, you are trying to hoodwink us into accepting that there is an evidential distinction between “choosing behaviour” and “non-choosing behaviour”. But “choosing behaviour” is just nonsense, there is behaviour that is volitionally chosen, and behaviour that is mechanical. And sometimes, as perhaps with amoeba/memristor the behaviours may be evidentially identical. There is only circumstantial evidence for volition; volition being what Wittgenstein referred to as “grammatical fiction”. What is required is a firm grasp of the grammar; faith in evidence, as you and Libet rely upon, results merely in a self-fulfilling prophecy. It merely results in looking “as if we had denied mental processes.”

Hi Tony,

Actually the book is available in the UK:

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/pieces-of-mind-9780198809524?cc=gb&lang=en

so I heartily recommend giving it a read! I’m not sure how to respond to your comment, clearly we need some idea of what choosing is to begin to seek evidence regarding it. I affirm this. I also don’t think I’ve committed any dubious grammar, or know what standards you’re using to make that assumption. Please do take a peek at the book and perhaps it will make more sense what I’m doing, as I don’t think I am succeeding in making that clear here.

Thanks Carrie,

“So do memristors choose? The first step to answering this question, and this is the focus of the book, is to ask: How do we determine what it is to choose? Do we rely on what’s familiar to us, or do we have better sources of evidence that might contradict what’s familiar to us?”

What would count as a better source of evidence for determining what a choice is than various actual choices? You seem to be suggesting that paradigm cases are all too familiar to be worth considering as examples and that we should be looking for “evidence” instead. Evidence of what exactly? Of how we use words? When someone asks us to explain a concept, are they looking for evidence?

You say that “Bennett and Hacker are quite clear… about the sort of evidence that might show that brains really have cognitive properties…” but that’s flatly contradicted when they write: “…we do not even know what would show that the brain has such attributes” (P. 72). You continue “…they just don’t think that sort of evidence is or will ever be available, and in this (as I argue in the book) they are wrong.” You seem to be overlooking that “The point is not a factual one.” (P.71) It’s a conceptual point, not one that we need evidence to resolve.

Are you not confusing evidence and examples?

“…the so-called mereological fallacy isn’t a fallacy – I suspect it arises by taking compositional principles that appear to hold for objects and extending them, mistakenly, to activities.”

So you don’t think it’s a fallacy to ascribe the ability to run to a leg or a foot then?

“…science is modifying the extensions of psychological predicates.”

The results of scientific experiments do not always have to make sense, whereas our statements do. When scientific experiments do not make sense, theories often need to be revised. Whereas when statements do not make sense, further clarification is needed or else we need to start again. You seem to think that science has some kind of jurisdiction over the extension of our ordinary concepts. That seems mistaken to me.

“Even if there is no evolutionary competition between parts of an organism (at least grant this is so), I fail to see why this should be a constraint on what a psychological predicate refers to. What the argument for that view?”

Intelligence is an attribute of creatures capable of learning, typically through sociocultural interaction. There is no such thing as an organ’s learning anything. Again, this is a conceptual point, not one that you can contradict by seeking out better sources of evidence.

“What would count as better evidence … than various actual choices?” Indeed. But of course how are we determining, as a starting point for discussion, which events are “actual” choices? The modified argument to other minds should make clear, I hope, that it cannot be taken for granted anymore than the only “actual” choices (“real” choices?) are the ones humans make, which are certainly among them but not necessarily all of them. To say “this is a conceptual point” presupposes (or so it would seem) the idea that the human choices fix the proper extension of “choice” (or that these are the only “actual” choices), which is the point at issue. It is an expression of the traditional anthropocentrism of psychology, not an argument for it. “But what other evidence could there be?” There can be, and is, scientific evidence, in particular of the sort that the example of the DDM (extended, inter alia, to fruit flies) was intended to illustrate.

I won’t go into B&H at length here, but when they say we do not know what would show that brains really have cognitive properties … (etc.), they are mistaken: we do know what would show this, just as we know what would provide evidence that fruit flies make decisions (and are affected by the same speed-accuracy tradeoffs in decision-making that humans are). When we turn to their claim about it being a “conceptual” issue, this is just another way of making the point I made above (and previously): the question is whether the features of choice that we associate with it because of our familiarity with human choices are essential to choice (constitute part of the core meaning of the concept, one might say) or whether they are not in fact essential to it. After this point I think we will begin to go around in circles (or continue to).

The mereological fallacy is a conceptual fallacy – i.e. that it is a conceptual mistake to ascribe a psychological capacity of a whole to a part. It is clearly not a conceptual mistake to ascribe rotating to a whole and a part (nor an empirical mistake). It may also be true that it is a mistaken to ascribe running to a part (a leg) as well as a whole (a dog), and this may be a conceptual ruling out: i.e. by definition, only items with legs can run, so snakes can’t run, as a conceptual matter). B&H claim is that psychological concepts are already such that ascriptions to parts are ruled out. This claim is based on the anthropocentrism about psychological concepts that I’m arguing against. “But what would could even count as evidence against this anthropocentrism?” That is where the importance of modeling practices comes in.

Carrie, you say: \\To say “this is a conceptual point” presupposes (or so it would seem) the idea that the human choices fix the proper extension of “choice” (or that these are the only “actual” choices), which is the point at issue.//

I don’t think that is the point at issue though. The issue is over the distinction between evidence and examples.

“If someone falls, breaks his leg, and lies on the ground groaning, it would be misleading to claim that this is good evidence for his being in pain. That suggests the possibility of better evidence to clinch matters, the intelligibility of doubt, the conceivability of coming to know that he is in pain in some other way than by reference to what he says and does.” (Hacker, “Insight and Illusion”, 1987, p.312)

The same can be said of decisions. If someone chooses to read a book all morning, it would be misleading to claim that this is good (or poor or anthropocentric) evidence for their deciding not to get up. You obviously think that “we have better sources of evidence that might contradict what’s familiar to us” whereas I think the question of evidence is irrelevant to the question of how we determine what it is to choose. We determine what it is to choose by examples, not by evidence.

The following video of Peter Hacker is characteristically clear about the problems at issue here. Start at the 3 minute mark if you are in a hurry. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dRmQ3eHhdqk

The standards I am using in criticising your grammar are what we might call the standards of good English. This standard is determined by custom and practice, something established through centuries and centuries of thoughtful, conceptual consideration. Whilst it often goes through revision because of evidential changes (advances in neuroscience; the coming of mechanical (rather than human) computers’ etc.) it needs to be done thoughtfully, with a good understanding of the grammar as it stands.

So, here is a detailed criticism of your understanding and use of the grammar.

From the Original Argument you state that “My behavior is caused by [something]”. That is, this something causes my behaviour;

The behaviour, which is mine, is caused by this something.

In your Modified Argument you qualify this and state:-

“My choosing behavior is caused by [something]”.

By inference from the Original Argument, we might again read this as:-

This something causes my behaviour.

But here, the behaviour (which is mine) is now a “choosing behaviour”. It is a behaviour that chooses. Just as a wagging tail is a tail that wags.

The word “choosing” is an adjective that qualifies the noun “behaviour”.

So, slightly modified from the Original Argument, we have:-

The behaviour that chooses, behaviour that is mine, is caused by this something.

But as I’ve said, this is nonsense. If I volitionally move my arm, then you are saying it is the movement of my arm which chooses to move my arm – not me; which is as ludicrous as saying my leg walks – not me, to use Jim Hamlyn’s example. Or are you actually claiming this?

But there is a second reading where we take “my choosing” as a possessive gerund.

This is equivalent to:-

Something causes me to choose my behaviour

Taken as a possessive gerund “my choosing behaviour” makes perfectly good sense (leaving aside questions of causality). “Choosing” is not here an adjective, but a noun. It does not qualify the word “behaviour”, so by this reading, the behaviour is not some nonsensical “choosing thing”; I am the “choosing thing”. The behaviour is just behaviour; unqualified.

But now, it is not the behaviour that is caused (or so it is claimed) by something, but my choosing. So you’ve completely changed the argument; you’ve shifted the goalposts. (And there are other problems.) This is the sleight-of-hand, the decisive movement in the conjuring trick that Wittgenstein warns against. I’m not saying you are purposely trying to hoodwink us, I’m sure this “decisive movement [is] the very one that [you] thought quite innocent.” What I _am_ saying, is this is why your argument is weak; because you don’t have a good grasp of the grammar. All you’ve succeeded in convincing yourself of, is the conflation of behaviour and choosing, convinced yourself that some behaviour _is_ choosing, and some not; by failing to distinguish “choosing” as noun from “choosing” as adjective. It is this that makes your grammar dubious. And a lot of people won’t notice this, which is why we need people like Hacker, who is good at this.

Behaviour is chosen, not choosing.

If it were that some behaviour _is_ choosing, as you say, then we would _only_ need behaviour to have evidence of volition. But behaviour is only evidence of volition, if it is behaviour _of_ a volitional being. It needs already be determined that it is a volitional being. As you acknowledge “clearly we need some idea of what choosing is to begin to seek evidence regarding it.” This is not itself determined by the behaviour, since, in principle, we could construct a device that mimics the behaviour of a fruit fly such that it passes the DDM test, just as we can construct memristors that mimic amoebae. These “mimickers” are not volitional beings, since they have no choice but to do what they do; by your account they are. But a fruit fly, I’m sure, does have a choice; and perhaps too an amoeba.

As for the notion that “human choices fix the proper extension of “choice” (or that these are the only “actual” choices).” We don’t learn the concept of choice from our human experience and extrapolate outwards. Children learn by playing with pets, toys, dolls, watching cartoons, actors acting, birds, insects, computers, robots, mechanisms. They learn that wasps will try to sting you on purpose if you attack them, but nettles won’t, not on purpose, nor needles; but they can still sting you. I don’t deny that my dogs choose to eat some things, on the basis that I would never choose to eat it! The only “anthropocentrism”, if you want to call it that, is that language is a human creation. As Wittgenstein puts it “If a lion could talk, we wouldn’t be able to understand it.” [Philosophy of Psychology – A Fragment §327]

“The standards I am using in criticising your grammar are what we might call the standards of good English. This standard is determined by custom and practice, something established through centuries and centuries of thoughtful, conceptual consideration. Whilst it often goes through revision because of evidential changes (advances in neuroscience; the coming of mechanical (rather than human) computers’ etc.) it needs to be done thoughtfully, with a good understanding of the grammar as it stands.”

No biologist worth a jot sits around ruminating on the grammar of ‘life.’ They study living things, as defeasible and messy as that initial classification is. If a lot ends up riding on whether some expression is a ‘possessive gerund’ then something is amiss.

Exactly. Which is why when biologists and the like attempt to derive philosophical implications from their work, they tend to make a hash of it, though not all do. The argument we are discussing here, is not a biological one, it’s philosophical.

First, there is no clean demarcation between science and philosophy. Second, we should not hypostasize ‘the standards of good English’. Such standards are not univocal. They are constantly evolving based on our current epistemic situation (as you acknowledged wrt the term ‘computer’). Third, such standards are actually fairly low on my list of priorities: I can say things that do not conform to the standards of good English but count as knowledge. To focus so exclusively on such surface grammatical constructs frankly comes off like the patronizing ghosts of ordinary language philosophy are here trying to set back philosophical progress.

To claim that talk of ‘choosing behavior’ is “nonsense”, as if that follows from some analysis of “the” standards of good English, is frankly rubbish. It is a perfectly reasonable way to talk even if, like ‘life’ it might not be perfect, perhaps a bit vague, and rough around the edges. That’s how most interesting ideas are especially early on. It’s enough to get us going.

“there is no clean demarcation …”

So what? Are you saying there is no demarcation at all? The terms “science” and “philosophy” evolve as all language does; sometimes because of changes in “our current epistemic situation”, sometimes for other reasons. The demarcation for the Ancient Greeks, if any, would be markedly different to ours.

But if I was about to undergo major brain surgery, and was given the choice between Hacker & Bennett to oversee the operation – it’s Bennett all the way down!

Hacker is IME a formidable philosopher, even though I don’t always agree with him. But he is not a formidable neuroscientist. So when he comes to write a book on the philosophical foundations of neuroscience, he collaborates with Bennett. And v.v.

Libet, a formidable neuroscientist I’m sure, chose to go on his own. And he made a hash of the philosophy.

“I can say things that do not conform to the standards of good English but count as knowledge.”

Such as?

“To claim that talk of ‘choosing behavior’ is “nonsense”, […] is frankly rubbish”

Indeed, which is why I haven’t claimed any such thing. I give a clear example where we can talk of ‘choosing behavior’ when it can make “perfectly good sense”. I.e when ‘my choosing’ is used as a possessive gerund, when ‘choosing’ is a noun. Here I am _not_ claiming that talk of ‘choosing behavior’ is “nonsense”. The contrary.

You’re treating ‘choosing behavior’ as if it must make sense in every linguistic context, or be nonsense in every linguistic context. I’m not. In the context Carrie Figdor uses it above (which is what I am discussing) – I stick by my claim that what _she_ says, is nonsense. In other contexts it makes sense.

I’m not saying it has to make sense in every context. I’m saying it made sense in the current context, and your claim that it did not wasn’t compelling.

Ok, explain to me what it means, by your understanding. Let’s start with whether you take “choosing” to be a noun or an adjective in the Modified Argument.

I would never start that way. The claim was ‘My choosing behavior is caused by X’. This is a loose way to talk about my behavior in some simple experiment as discussed in the post (choosing a red or a blue chip; or at a vending machine, you have to choose between a chocolate bar or a box of raisins). That’s it.

Feel free to recast it as a verb, adjective, noun, a subjunctive conditional, a question, an exclamation. What I care is that it is good enough. That is, it is reasonable to talk about picking a chocolate vs a box of raisins as making a choice, or ‘choosing behavior’? Yes. Good. Then let’s be charitable, not pedantic, and see where it takes us.

And that’s what I was getting at when I wrote, “It is a perfectly reasonable way to talk even if, like ‘life’ it might not be perfect, perhaps a bit vague, and rough around the edges. That’s how most interesting ideas are especially early on. It’s enough to get us going.”

I think it’s a mistake to regard “choosing behaviour” as a vague but interesting idea. Should we regard believing behaviour or thinking behaviour as interesting ideas too?

This is false equivalence because, unfortunately, only one side of the debate is based on looking at the uses of psychological predicates across an enormous variety of taxa in papers published in such journals as Science, Nature, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, Plant Signaling and Behavior, Trends in Microbiology, Journal of Bacteriology, PLoS ONE, Journal of Physiology, Neuron, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Journal of Vision, Current Biology, Physical Review Letters, and so on and so on and so on. Once both sides are cognizant of the uses that the Literalist view attempts to account for, genuine debate is possible.

“Should we regard believing behaviour or thinking behaviour as interesting ideas too?”

Sure. We’ll find out soon enough if it was a good strategy based on the specifics. More relevant, the study of behavioral choice has ended up being very fruitful.

I should admit that, probably more than Carrie, I am much more interested in the phenomena than in the words. I’d rather have you explain the mechanisms by which a rat chooses between a candy bar and a raisin, than the jargon you use to describe that process.

Thanks for answering my question; although you probably don’t realise that you have answered it. In acknowledging that we are “talk[ing] about my behavior” you are clearly reading the opening gambit as using ‘choosing’ as an adj. So I’m afraid that this is exactly the way you did start, in spite of your protestations that you never would start that way.

And having made it clear you read it as an adj. then that is not “loose”; it is quite clear. What is not though clear, is what “choosing [adj] behaviour” itself means. How can the movement of my arm, choose to move my arm?

But then in your 2nd paragraph you choose to recast it as a noun where, as I’ve said, it can make a bit more sense. But even here you make a hash of the grammar. Yes, it is “reasonable to talk about picking a chocolate vs a box of raisins as making a choice”, but this is “my choosing [noun] chocolate”, not “my choosing behaviour”; I didn’t choose behaviour, I chose chocolate. By omitting the possessive “my” it is fair to read you as recasting it back to an adj. in order to make you argument look more persuasive. I don’t think you’re doing it purposely, I don’t think you are aware at all of what you are doing. Nor is Carrie. But some of us are.

I will not “feel free to recast” the term in question. If it is ambiguous as to whether it is a noun or adj, then I will challenge the person making the assertion; ask them ‘what do you actually mean here?’ I will not cast it in the way you have, firstly as an adj., and then freely recast it as a noun and back again, in the hope that nobody will notice what I’ve done, agree with my conclusions and praise me as some wonderfully insightful chap. Sorry, but you can only fool some of the people, some of the time…

As a blood relative of Wittgenstein, I do appreciate your attention to some of his philosophy. But perhaps it is time to just suggest once more that Pieces of Mind might be worth reading!

Best of luck with your book.