Although introspectively familiar, it is hard to exactly pinpoint the nature of the specific relationship that we have uniquely with our own body. We are aware of our bodily posture, of its temperature, of its physiological balance, of the pressure exerted on it, and so forth. Insofar as these properties are detected by a range of inner sensory receptors in the skin, joints, muscles, tendons, inner ear, and internal organs, one may conceive of bodily awareness on the model of perceptual awareness. Yet in many respects bodily experiences depart from standard sensory experiences. What are the consequences of the inside mode of our acquaintance with it? Is the body presented to us as one object among others? Or is it presented to us in a special way?

Thanks to their privileged relation to our body, bodily experiences seem to afford awareness of our body as being our own. Consider the following basic example: I touch the table with my hand. I feel the table but it seems also that I feel that the hand that touches it is mine. This type of self-awareness is known as the sense of bodily ownership, for want of a better name. Ownership is what may be called a high-level property, a normally permanent one (although we shall see that this is not always the case), and thus rarely at the forefront of consciousness: it does not attract attention because it normally does not change. Consequently, there is an ongoing debate over its very existence: do we actually feel the body as our own, or do we merely know that it is our own? And how to best characterize this minimal form of self-awareness? In sensory terms? Agentive terms? Affective terms? Or in cognitive terms?

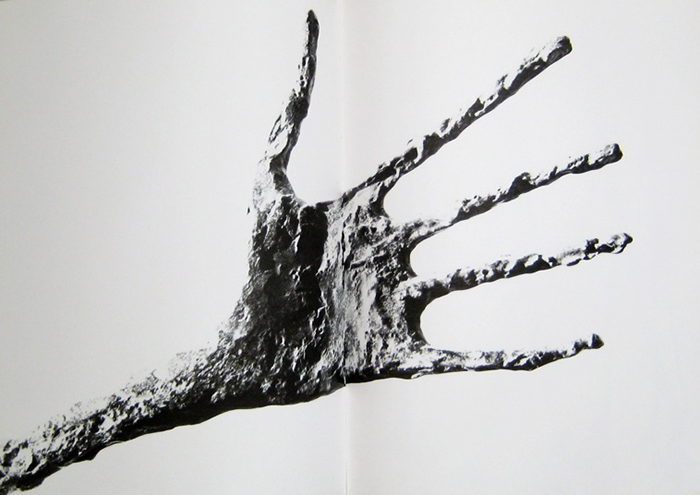

To answer these types of question, it has proved fruitful to compare two situations: one in which the high-level property is instantiated and one in which it is not. One can then analyze what changes in our experience. Interestingly, it has been recently shown that one can artificially induce a sense of ownership for a fake hand or for a virtual avatar. Furthermore, it has been found that some neurological and psychiatric disorders can cause patients to deny ownership of their own limbs. These borderline cases shed light on what it takes to gain ownership over an external entity and to lose it for one’s own body. These last twenty years have actually seen an explosion of experimental works on body representations, bodily illusions and bodily disorders. The sole notion of body ownership gives rise to more than 6000 references on Google scholar, half of them published in the last three years. My book, Mind the body, An exploration of bodily self-awareness(OUP, 2018) aims at providing a theoretical compass to navigate within what has become an exploding research minefield.

In the forthcoming four posts that will appear this week, I will pursue the following tasks:

- A phenomenal contrast for bodily ownership: I will take as a starting point the subjective reports offered by patients who deny ownership of their own limbs and by experimental subjects for whom it seems that a rubber hand is their own hand. I will argue that there is no convincing account of those cases in purely cognitive terms.

- What is the experience of bodily ownership? I will examine different phenomenological accounts of ownership and defend my own view in affective terms. More precisely, I will argue that the brain evolved specific mechanisms to protect one’s body for survival, and that the feeling of ownership consists in the awareness of the unique significance of the body for the self from an evolutionary perspective.

- What kind of first-personal content? I will clarify why the feeling of unique significance is not just an affective side-effect of the feeling of ownership instead of the feeling itself.I will further show how my theory can account for the first-personal character of the sense of ownership.

- A taxonomy of theories of ownership: I will argue against the inflationary/deflationary dichotomy often used in the literature to classify the various conceptions of ownership and offer a richer conceptual roadmap, which hopefully will help further debates and avoid cross-talk.

Is the feeling of bodily ownership a phenomenal characteristic of first-order experiences of the body, or is it a separate higher-order self-reflective experience? Here’s a question that arises from this: My dog touches her ball with her paw. Is there something about her conscious experience that (whether she knows it or not) constitutes a feeling that the paw is hers. Or is the feeling of ownership a separate self-reflective attitude that most people think dogs incapable of? I take it that the phenomenal account that you outline in your post above inclines to the former answer. On the other hand, describing the feeling of ownership as “higher-order” suggests that it is self-reflective.

Here I draw a distinction between low-level and high-level properties that can be experienced in bodily sensations. A smooth texture, for instance, is a low-level property, directly detected by tactile receptors. Bodily ownership is clearly a different type of property. In this sense, it can qualify as a high-order property. However, this does not entail that the FEELING OF ownership is a high-order reflective experience. At least, not more than the experience of pine trees or other high-level properties in perception. Consequently, if the dog has some self-referential abilities, then it can experience a sense of ownership.

To me, it seems inevitable that all ‘lower’ forms of life have self-ownership of their own bodies, because they would eat themselves if not. That is, the closest source of protein would be their own limbs, so lacking a sense of ownership of that limb would likely mean self-cannibalism. Therefore, self-ownership of the body must be a very ancient evolved trait, clearly for the sake of survival of the organism. It is also clear, since some animals will chew off their own limbs in order to escape a trap, or shed their tails to escape, that limbs are not the highest body part on the self-ownership hierarchy. It is probably no mystery that we tend to see our heads as more us than our limbs, because that hierarchy is probably pretty old, as well.