Luis H. Favela and Edouard Machery

We thank Inês Hipólito for taking the time to offer her thoughts about the concept of representation in the brain and mind sciences in response to our work. Hipólito kindly notes the strengths of our project, such as its inclusivity of participants from a range of disciplines, strength of experimental design, and credible findings.

After situating our work within a historical context that begins with cognitive psychology’s commitments to information processing conceptions of human behavior and that continues with more recent developments in the form of “Embodied Cognitive Science (ECogSci),” she proposes that our finding that neuroscientists and psychologists appear to be uncertain about what brain activity entails representations invites researchers to shift away from cognitivism and explore alternatives to the computationalism at the heart of much cognitive science. In her opinion, this uncertainty provides support for ECogSci approaches and, more specifically, for the idea that “mental representation is an agent’s enculturated skill.” When taken together with other challenges (e.g., the influence of computationalism upon funding and peer review), our study further raises the possibility that the cognitive sciences (broadly construed) are facing a “Representation Crisis.”

In our original paper, we sketched three possible reactions to our finding: reform the concept of representation, eliminate it, or explain why it has the features it appears to have. Hipólito’s broad-ranging discussion appears closer to the first option. Though it is clear that Hipólito finds cognitivism problematic, she seems keen to preserve the concept of representations as central to alternative theoretical frameworks, including ECogSci: “The future of cognitive science is one of vibrant potential … Mental representation is but one thread in the rich fabric of cognitive experience.” Consequently, elimination does not seem to be an option for her.

Admittedly, most brain and mind scientists might not find elimination a practical or desirable option either, but her continued embrace of the concept of representation raises questions about how “radical” Hipólito’s call for change really is. Furthermore, we wonder how solving the “Representation Crisis” would fit with our two other options. We suspect that Hipólito might not be entirely hostile to elimination, that is, to removing the concept of representation from investigative and explanatory practices, but we wonder what she would have to say about the third option: to embrace what historian of science Hans-Jörg Rheinberger calls an “epistemology of the imprecise.” Here, a concept’s lack of clarity or precision is a virtue, at least regarding its ability to pollinate across disciplines; for if a concept is too precise, then it could not be applied across contexts. If this is the right approach to the concept of representation, our findings only support a move to alternatives to cognitivism and computationalism if pollination across the disciplines of cognitive science has so far been of limited scientific value.

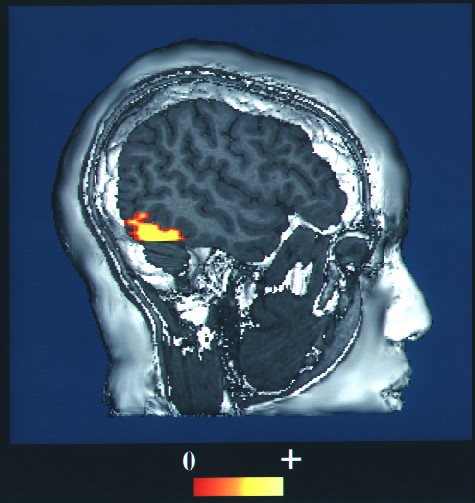

What is interesting about this discussion is a total failure – unless I missed something – to recognize that the brain is primarily an imaginative – ie. mapping device. That’s what images do – they map the world. That’s what Ramachandran said – everywhere you look in the brain you see maps. Maps not just of the internal body but of external bodies. The brain maps the world very flexibly not just literally/ cartographically. Not just photographically but pictographically and idiographically. Bodies seen at increasing distances gradually lose their distinguishing characteristics and become just blobs – like the balls of an abacus or boxes of a diagram.

The way forward from the representation crisis is to recognize that there are two main, distinct kinds of representation. Images- or maps – of the world that reflect the world with various levels of fidelity/realism. And names of the world – that simply label the world and its bodies without representing their forms – i.e. symbols, words, numbers. It is much more efficient to just name a body – To say or write C-A-T is much simpler and quicker than drawing an icon of a cat. But with efficiency comes loss of clarity of thought. And loss of creative reasoning. You cannot see whether new bodies fit together – whether a particular foot fits a footprint – unless you can see – map their forms onto each other

Mental images ground the body in the world. they are essential for mapping onto the agent’s body on one side and the external bodies of the world on the other – and thus direct not just thought but action-in the world via vision, movement (configuring/positioning our own bodies) and manipulation of other bodies Symbols cannot ground anything. They are just convenient subtitles on our images-maps.

The crisis of representation then is also a crisis of computation and semiotics. The painful but necessary conclusion is that if we want machines that can emulate human and animal intelligence – “AGI” — symbolic/digital computers will be inadequate. We will have to devise imaginative/mapping mechanical brains for robots that directly map the world like the real neural networks of our human and animal brains.