(See all posts in this series here.)

In Chapter 2 of MoM and an earlier book (second edition forthcoming), I have defended the selection for action view of attention.

A subject attending to target T is the subject mentally selecting T to guide their action.

Attention guides behavioral response in action. A subject visually attending to T to grasp it is the subject’s visually selecting it to guide the grasp movement. A subject mnemonically attending to T is the subject’s maintaining or encoding it in memory. William James said this is something we all know: a subjects attending to T is the subject’s mind grasping T in order to deal effectively with it. I understand the emphasized part as the guidance of behavioral response in acting on T. I’ll speak of the different (mental) modes of attention as “m” so, m-attention such as (m=) visual or cognitive attention.

Keeping with my aim to reduce controversy, I highlight only the sufficient condition:

if a subject m-selects a target to deal with it, then the subject is m-attending to it.

The condition is enough to do much of the work any theorist wants from attention. Indeed, I have argued that this condition is built into the experimental paradigms in cognitive science used to probe attention. What ordinary persons know is also what experimentalists know. Philosophers drawing on empirical work on attention commit themselves to the sufficient condition. Given this unanimity, the condition is ground zero for reflecting on attention (MoM, Chp. 2.2).

For the actions of interest in the last post, each such action involves attention. I’ll just run modus ponens with the image from Post 1 (Chp. 2.3):

Figure. Solving the Many Many Problem. Solid arrow indicates attention, the mind’s selecting a target to deal with. © Wayne Wu

When we act, the mind selects a target, say visually, to guide response (bolded solid lines). The agent’s selecting a target to guide response describes part of the path taken, namely the action executed. Attention is part of action, not an extra ingredient (Chp. 2.4). Accordingly, in endowing an agent with input and output capacities that define the Selection Problem, and a set of biases needed to solve it, nothing more need be added to have attention in place. Attention comes for free when the action engendered. Attention picks out the front end selectivity of inputs entailed by solving the Selection Problem. There is a philosophical upshot: to understand agency completely, you cannot limit yourself beliefs, desires, intentions, movements. Attention is present at the core of all actions as guidance (in Chp. 1.9, I criticize Frankfurtian accounts of guidance).

Unfortunately, philosophers have assumed that the sufficient condition is easy to refute. A simple formula is to identify selection that isn’t attention. So, reaching for a glass of wine as a waiter walks by while you are conversing during a gala is said to demonstrate visual selection without attention. I find these responses to be question begging.

Let’s however just note that recognizing the pervasiveness of automaticity is crucial. In reaching for the glass, you don’t intend to attend to the glass or are (access) consciously aware of attending, but it does not follow that you don’t attend. Attention to the glass can be automatic, something you don’t notice. Indeed the bulk of attention in waking life is automatic. If covert visual attention programs overt visual attention (eye movement), then at 1 to 3 saccades a second, in an hour, you make up to 10,000 overt and covert shifts of visual attention. You are access aware of almost none of those, yet the fluidity of your agency depends on those shifts. What the objectors miss is automatic attention. We are often not aware of automaticity, and important theme I will return to later. (on nonobservational access to intentional action, see (MoM, Chp. 4).

The pervasive automaticity of attention expresses different aspects of mind. Automatic perceptual attention is a crucial part of skill such as performance in sports, the arts, and medicine. Automatic cognitive attention is expressed in mind wandering, in recollection, in problem solving and in bouts of creative cogitation. Implicitly biased behavior is often driven by automatic attention. Attention, as part of action, is always biased, positively or negatively (or neutrally). Understanding these automatic biases is critical to understanding the listed phenomena, and a technical notion of automaticity is crucial (Chp. 1.4)

Let me give one compelling example of how attention is automatized in a way that tracks skill (MoM Chp. 5.5), indeed exemplifies a type of epistemic virtue.

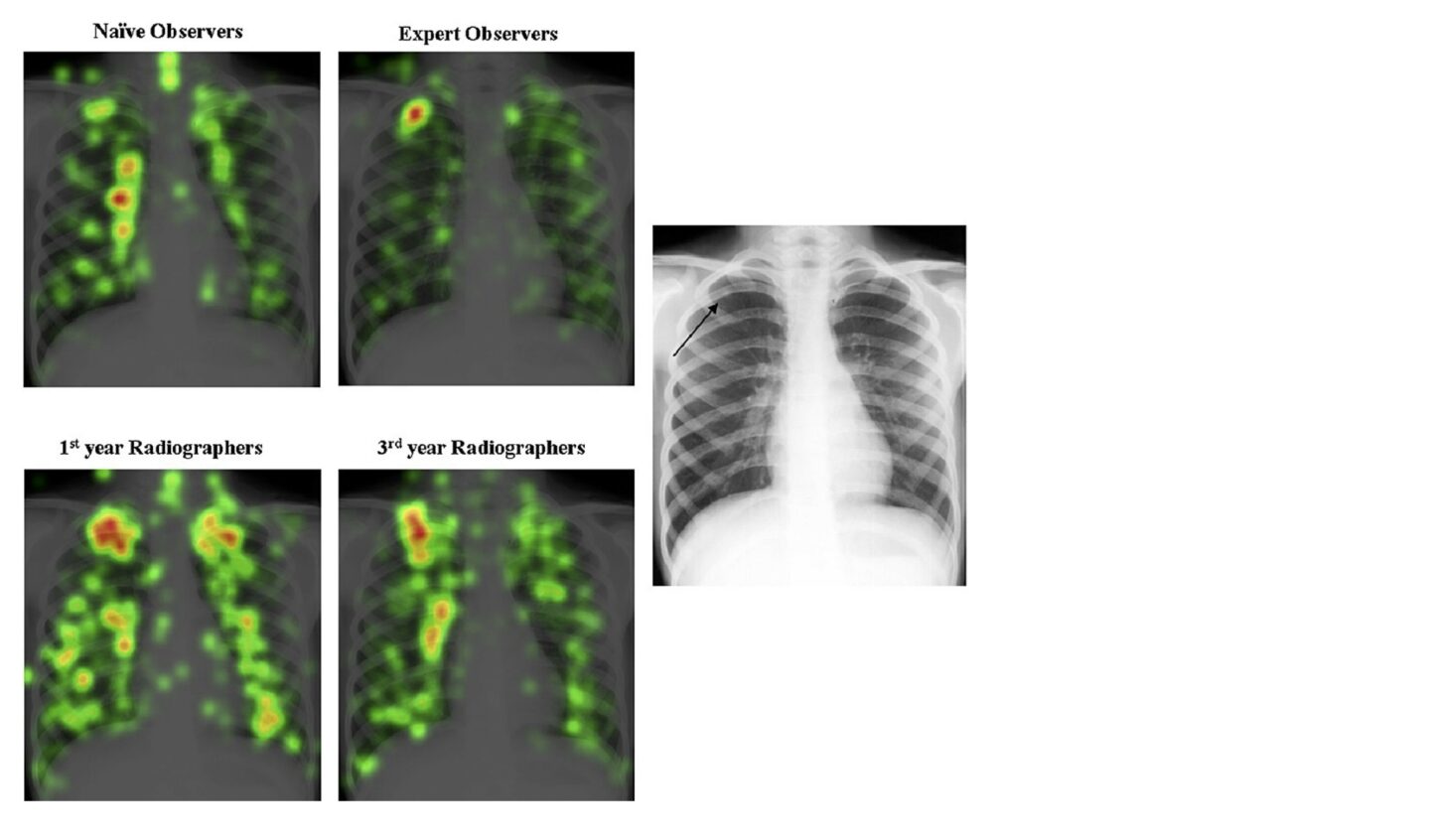

Figure. Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Figure is reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons from Timothy Donovan and Damien Litchfield. 2013. “Looking for Cancer Expertise Related Differences in Searching and Decision Making.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 27 (1): 43–9.

The figure presents a heat map of fixations of how subjects visually search an X-ray for potential anomalies. Subjects with no medical training focus on “salient” but medically unremarkable features. Subjects with various levels of medical training search more broadly, likely applying a search rule. The striking panel is the expert radiologist where the anomaly is like an alarm, grabbing attention. Visual search changes with learning. Since the X-ray presents a complicated Selection Problem, the automatic pattern of eye movements reflects a set of biases that tracks levels of training, the subject’s skill, and a type of epistemic orientation to gathering appropriate information to inform medical judgment (diagnosis).

Using the control-automaticity distinction, in each case, the subject’s visual search (attention) is goal-directed to locate anomalies. Their search is intentional in being a search to inform medical judgments. Yet each specific eye movement and the overall pattern is not intended, at least not at the fineness of grain revealed in these images. This change in the balance of automaticity and control reflects learning and the development of skill.

The take home messages are this: attention is part of action, we all know what attention is in that in actions of theoretical interest, it is a subject’s selecting a target to respond to, and much of such attention is automatic as we have defined. In the next post, I delve into intention, the source of control, as “memory for work”.