I find the challenges to the coherence of inferentialism much more powerful than the objections inherent in alternatives. That’s why I devote more time in the book to making the case that inferentialism is coherent, and to explaining what form it could take.

Perhaps a first type of challenge to inferentialism’s coherence comes from the idea that something in the nature of experience precludes it from being epistemically appraisable, and therefore from being the conclusion of an epistemically appraisable inference.

For instance, it’s natural to think of perceptual experience as something we come by passively, and something that we can’t explicitly think our way into, the way we can reach a verdict on a question through active inquiry and reasoning. When you think through whether it would be better to leave town today or tomorrow, you bring to bear various considerations and somehow figure out what’s best. But nothing like this, it seems, could issue in a perceptual experience.

My strategy for answering this version of the first challenge is to distinguish between modes of passivity and argue that none of them are distinctive of perceptual experience, but apply to belief as well. And so if these kinds of passivity were grounds for precluding experiences from being potential conclusions of inference, they’d be grounds for precluding beliefs from the same. This argument comes in Chapter 3.

A second version of the challenge appeals to the difference between perception and cognition. Some ways of drawing this distinction appeal to the format or structure of perceptual states. For instance, according to a tradition inspired by Bertrand’s Russell’s theory of acquaintance and Gareth Evans’s theory of demonstrative thought, perceptual experiences (putting aside hallucinations) are differentiated from thoughts by virtue of their structure. They’re structured by an acquaintance relation to objects you perceive. On this family of views, which is sometimes called Naive Realist Disjunctivism (and other times the Relational view of perceptual experience), it might seem hard to see how a state structured by a perceptual relation could be the result of an inference.

I am not entirely sure how to answer this challenge. I suspect that inferentialism is compatible with Naïve Realism in its letter, though perhaps not in its motivation, to the extent that it is motivated by the idea that the kinds of experiences it’s analyzing are precisely those in which certain qualities in the world “announce themselves” to you, independently of whatever other psychological states you’re in.

A second type of challenge to inferentialism’s coherence is that something in the nature of inference precludes it from having experiences as its conclusions. For instance, a natural idea, defended by Frege and others, is that drawing an epistemically appraisable inference from state X to state Y has to involve taking X to support Y. After all, not any old transition from X to Y will be an inference. The mind might just blankly move from believing P, and believing If P then Q, to believing Q. Not every such transition is an inference. But if the thinker takes P and If P then Q to support Q, then this ‘taking’ seems like a good candidate for differentiating between blank transitions in which the mind is potentially ignorant of any relationship at all between Q, on the one hand, and both: P and If P then Q, on the other.

Does the idea that inference involves a ‘taking’ condition challenge inferentialism? I think it does. If inferentialism is true, and if it can explain the epistemic downgrade of Jill’s experience, then the inferences that lead to experience will occur outside Jill’s awareness. That’s why it’s hard to see how Jill could both infer her experience (presenting Jack as angry) from her fearful suspicion that he’s angry, and be in total ignorance of the fact that her fear has influenced her experience.

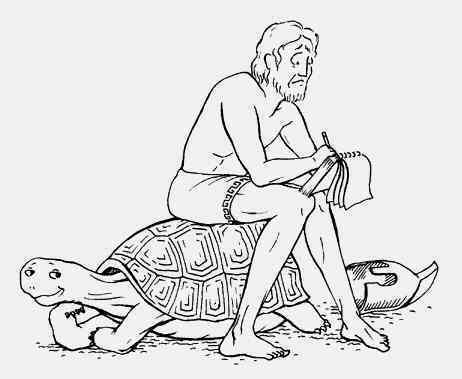

The idea that inference involves a ‘taking’ condition faces difficulties, starting with how to differentiating the ‘taking’ from another premise. (If it’s a premise that: both (P and If P then Q) support Q, a regress threatens – the one discussed by Lewis Carroll in “What the Tortoise said to Achilles”). Valiant efforts have been made to avoid the regress, by explaining how the ‘taking’ condition could have a status other than another premise. But even if these efforts succeed, I think an important conceptual challenge to inferentialism remains. According to the challenge, if inferences are epistemically appraisable, then the subject has to in some way regard the inference’s conclusion (the experience) as rationally related to the inferential inputs. And there’s no way for Jill to regard her fearful suspicion as rationally related her experience, consistently with her being so completely unaware that it’s influencing her experience.

My answer to the challenge from inference is to outline a theory of inference that does not involve a taking condition, and to illustrate using a range of clear cases of inferences how they could occur, consistently with ignorance of the sort we find in Jill. This is the topic of Chapter 5 of The Rationality of Perception. At the end of the chapter, I argue that this kind of inference could in principle be found in the phenomenon of memory color. Memory color is a phenomenon in which stored information about things (such as that bananas or banana-shaped things are yellow) influences color perception. (Zoe Jenkin, a graduate student at Harvard, is writing a thesis arguing that intra-perceptual processes including the ones involved in memory color are epistemically appraisable, but not due to inference – due to the other rational relationships between experiences and their precursors).

Hi Susanna. Thank you very much for your post! I have two questions about inferentialism. The first question is about what counts as inferential inputs of a perceptual inference in a particular case. For example, in the Jill and Jack case, is Jill’s fear the only inferential input of her perceptual inference? What about the memory color case? In principle, the relevant effect can occur at different stages of the perceptual processing. If the effect happens even before the generation of an unconscious perception (not to mention the experience), how to think about the relevant perceptual inference?

My second question is about whether inferentialism wants to apply all the evaluation rules of belief inferences to perceptual inferences? One worry about such a move is that when we evaluate beliefs inferences, we often have an (at least somewhat) ideally rational subject in mind. However, perceptual inferences, due to how perception generally works, might fail to count as ideally rational in a large number of cases. This could be worrisome since it might lead to a skeptical conclusion about perceptual justification.

For example, in a Bayesian framework, the perceptual system chooses the hypothesis with the highest posterior probability to produce an experience. However, the highest posterior probability might be below 0.5, which might make the inference jump to the conclusion.

Hi Lu, thanks for the questions. Let me take the second

one first.

On ideal reasoning: Even if very idea of ideal reasoning is incoherent (for instance because it would have to satisfy multiple norms that can’t simultaneously be satisfied), there will still be norms of inference. So inferentialism doesn’t rely on the idea that norms of inference are defined in terms of ideal reasoning.

As I think of it, “Jumping to conclusions” is a placeholder for a kind of proper inferential response to inferential inputs. Substantive theories of reasoning can fill in the specific account of what it is to jump to conclusions.

To illustrate, suppose high practical stakes reduced the justification you could get from forming belief X on the basis of belief Y, so that with high stakes you’re only justified in the Y-belief on the basis of the X-belief to degree n, whereas with lower stakes you’d be justified to degree n+.

Degrees of justification are a different thing from degrees of belief. But it’s natural think that the measures of strength are systematically related. If they are, then if you’re justified to degree n in belief X, then

there’s some measure of strength of belief X that you should have, such as strength n*. If you have belief X at some high level of strength, such as n*+, then its strength would exceed the appropriate degree of justification for that situation.

We can use these distinctions to define one thing that jumping to conclusions could be, in a framework with strength of belief and practical stakes. Suppose you have you infer belief X at strength-level n*+ from belief Y under high stakes. Given the high stakes, you should have belief X only at level n*. That would be an example of jumping to conclusions. Nothing in this story requires ideal reasoning. What it requires is the idea that degrees of justification determine degrees of belief.

On what counts as inferential inputs: it depends on the case. Jack and Jill’s case is under-described in this regard. In chapter 8 on evaluative perception, I argue

that fear is internally related to a kind of confidence. On that view, Jill infers from her confidence. In the case of memory color, there are also various

candidates for inferential inputs, but at a minimum what’s needed is a generalization about color (such as that banana-shaped things are yellow) and an informational state about the thing you’re seeing.