“If he [Descartes] had examined that other, deeper opening upon things given us by the secondary qualities, especially color, then….[h]e would have been obliged to find out how the indecisive murmur of colors can present us with things, forests, storms—in short the world. …. But for him it goes without saying that color is an ornament, mere coloring…….” — Merleau-Ponty (1964/2001:294)

The quotation comes from the late essay on painting, “Eye and Mind” (“L’oeil et l’esprit”). The context is a discussion of what Merleau-Ponty takes to be a telling omission in Descartes’ Dioptric, a celebrated work on vision, optics and graphical representation. Descartes presents copper engraving as the paradigm of picture making and is silent on the operation of painting. This leaves us with the implication, as Merleau-Ponty puts it, “that the real power of painting lies in design [i.e. line drawing], whose power in turn rests upon the ordered relationship existing between it and space-in-itself” (294-295). Yet, Merleau-Ponty insists, colouring is not mere ornament—it is an “opening upon things” (“ouverture aux choses”).

I found this passage shortly after completing the manuscript for Outside Color. As chance would have it, it captures very nicely one of the central ideas of the book, which is that colour and colour vision are a means of perceiving an array of properties, qualities and relationships amongst objects in the world around us, and that we must break away from the habit of thought that takes chromatic vision to be simply colouring in a pre-given visual world of shapes, textures, boundaries and distances. As Akins and Hahn (2014) put it, chromatic vision is about “more than mere colouring”.

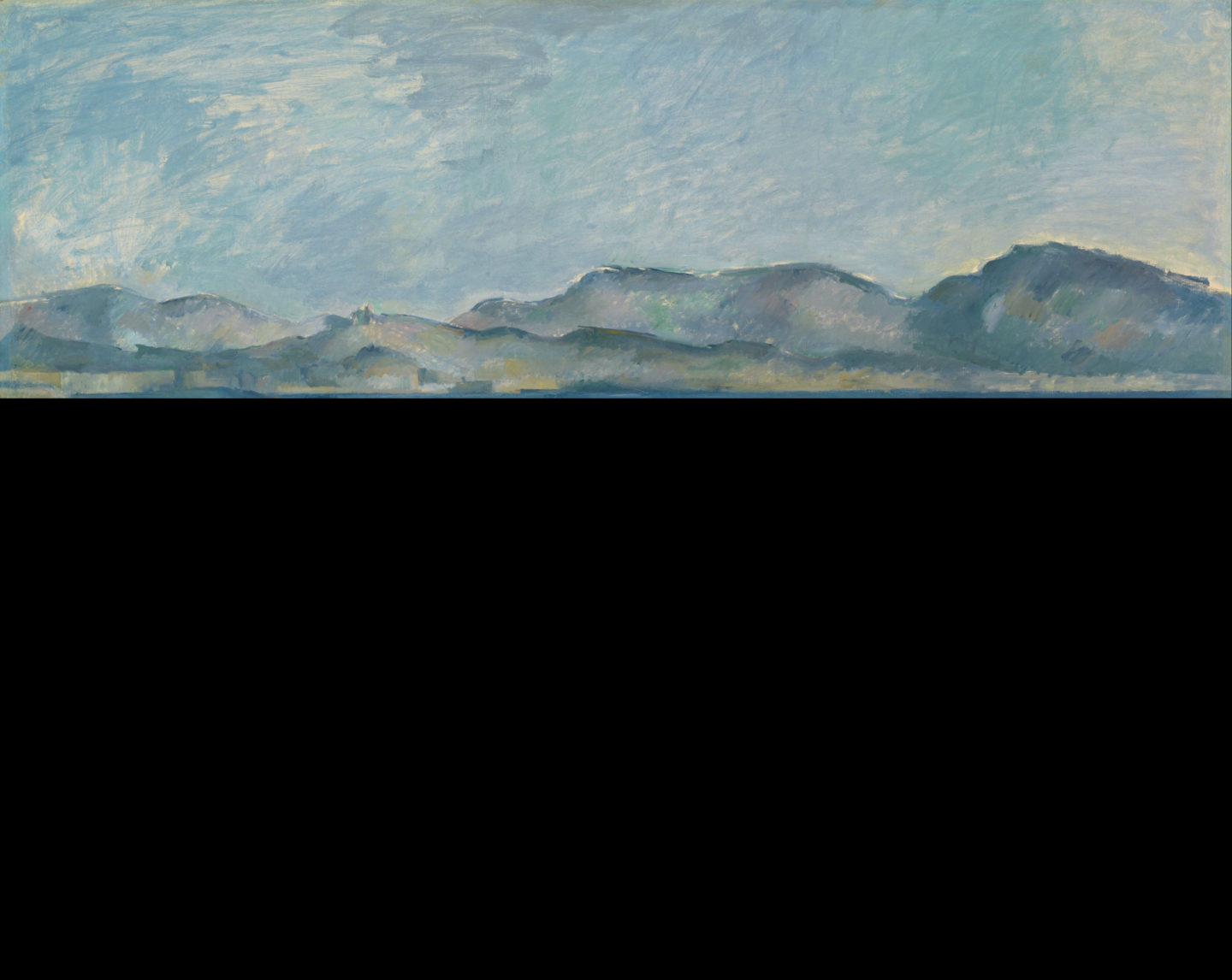

Take, for example, this landscape panorama from the blue mountains. As the hills recede into the distance their colour becomes bluer and less saturated:

Chromatic vision informs us not just about the colours of the trees, but of their distance from us—an effect noted by perceptual psychologists (Troscianko et al. 1991), and by painters.

Much recent work on human vision has focussed on the interaction between colour and the other visual submodalities like shape, depth and lightness perception. Similarly, Matt Fulkerson has recently written on this blog about the integration of different streams of touch information which were once treated as separate. My own perspective was influenced, in particular, by findings from Fred Kingdom’s lab at McGill University. In one review, Shevell and Kingdom (2008) catalogue the evidence that colour vision contributes to all of these important visual tasks:

- segmentation of objects

- perception of form or shape

- grouping of objects

- perception of contours

- perception of texture

- object detection

- object identification

- perception of depth

- perception of the motion of complex objects

- recognition of shadows

In my previous post I proposed that the debate over colour ontology has been over-fixated on the question of correspondence, whether anything in our inventory of mind-independent or physical properties corresponds to the colours that we see. My point here is that colour vision allows us to do much more than just experience colour, and that this is so whether or not any property in the external world corresponds to our chromatic experiences. So what colour ontology should we opt for? I will hazard an answer in the next post.

Concluding here, I would like for a moment to consider why Merleau-Ponty speaks of colour as an “indecisive murmur” (“le murmure indécis des couleurs”). I cannot say what the connotations are in the original French but to me the metaphor invokes indistinct speech, the flow of water, rustling matter, or the footfall of distant events. Colours, I first thought, are not at all like this; they are immediate, bright and clearly delineated. Yet when we remember that Merleau-Ponty is writing about colour in painting we may note that hues arranged on canvas, viewed at close range, are typically dappled and varying irregularly within the outline of a surface.

That is because the painting must convey the fine texture of hue and brightness that occurs with the irregularity of lighting and shadow (what vision scientists call “luminance noise”). The painterly eye attends more to the inconstancy of colour than is usual in everyday life, and it is this attention to detail that often makes a painted world so strikingly real. However we can all choose to notice that the colours around us also present themselves in a vague way. For instance, with the play of sunshine on foliage we can appreciate that the greens are murmuring and rippling, not flat and uniform; but still presenting us with the tree.

References:

Akins, K. and M. Hahn (2014). More than mere colouring: The role of spectral information in human vision.”. British Journal of Philosophy of Science 65, 125–171.

Merleau-Ponty, M (1964/2001) “Eye and Mind” in Continental Aesthetics, R. Kearney and D. Rasmussen (eds.), trans. Carleton Dallery, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Shevell, S. and F. Kingdom (2008). Color in complex scenes. The Annual Review of Psychology 59, 143–166.

Troscianko, et al. (1991). The role of colour as a monocular depth cue. Vision Research 31(11), 1923–1930.

The final couple of sentences in today’s extract hit the nail on the head: The painterly eye attends more to the inconstancy of colour than is usual in everyday life, and it is this attention to detail that often makes a painted world so strikingly real. However we can all choose to notice that the colours around us also present themselves in a vague way. For instance, with the play of sunshine on foliage we can appreciate that the greens are murmuring and rippling, not flat and uniform; but still presenting us with the tree.. We can report colour both as a property of a distal object and as a sensation and can choose to which of these we attend. As Thouless pointed out in his 1931 paper “Phenomenal regression to the real object” our reports of sensation are typically contaminated by our percepts of distal objects. This is reflected in more modern measures of colour constancy where constancy indices for hue/saturation matching are lower than those for paper-matching tasks. The task a figurative artist faces is to reduce contamination by automatic constancy processes (see our paper on colour constancy without colour experience) and reproduce something of this experience.

Thank you! I will take a look. I’m currently working on a paper on the “stimulus error” (i.e. in your words, “contamination by automatic constancy processes”) in the history of perceptual psychology and how it relates to the debate over hue vs. paper matches more recently.

Does the book by any chance talk about why we see the colors we see? And why it might differ from person-to-person in some cases?

Hi, that’s a good question but goes beyond the scope of the book. There is a big experimental literature on the “colour blind” — dichromats and anomalous trichromats (and possible tetrachromacy in their female relatives). In philosophy, Justin Broackes (Brown) has done really interesting work on what such individuals experience, questioning the standard phenomenological descriptions.

Thanks for an illuminating post, Mazviita!

I will focus on the case of color functioning as a depth cue (blue and less saturation indicates long distance). I want to draw an analogy to the spatial case. In the case of spatial properties, we have the familiar story in which we see a line of trees, and the distant tree in some sense looks smaller than the tree nearby. So size, in some sense, is a depth cue.

However, the “size” in question is not objective size (the distant tree is not really small). Rather, it is “perspectival size” (which is often taken to be a relational property of the tree). In addition to seeing perspectival size we also see the actual (objective, mind-independent) size of the tree, which remains constant to us despite changes in perspectival size (“size constancy”).

If the color case is similar to the spatial case, then when the “blue” functions as a depth cue, this blue not an objective color, but rather a perspectival color. Perspectival color is probably relational. But in addition to seeing perspectival colors, we see “constant” colors (“color constancy”), and these might be objective, mind-independent properties.

Perhaps my point is this: color realists (as far as I understand) are concerned with constant colors, not perspectival ones. So the claim that blue in “blue as a depth cue” is not objective, mind-independent, but is instead relational (or pragmatic, as you hinted in your previous post) is apparently compatible with color realism, because “blue as a depth cue” is a perspectival color, not a constant color.

Hi, and thank you for this important question. Yes, we can think of the blue of the Blue Mountains as a depth cue like the others. That kind of colour is certainly perspectival. Then we have the question of whether there are non-perspectival colours, and whether this gives us reason to be realists about colour. I don’t think the phenomenology of colour constancy is as conclusive as realists like to say it is. The point in the last paragraph was that even when the colour of an object might on first reflection appear definite and uniform, there’s a shiftiness to it which appears on closer inspection. Given the indecisiveness of the phenomenology, I’d say that colour realists need other reasons to motivate their view.