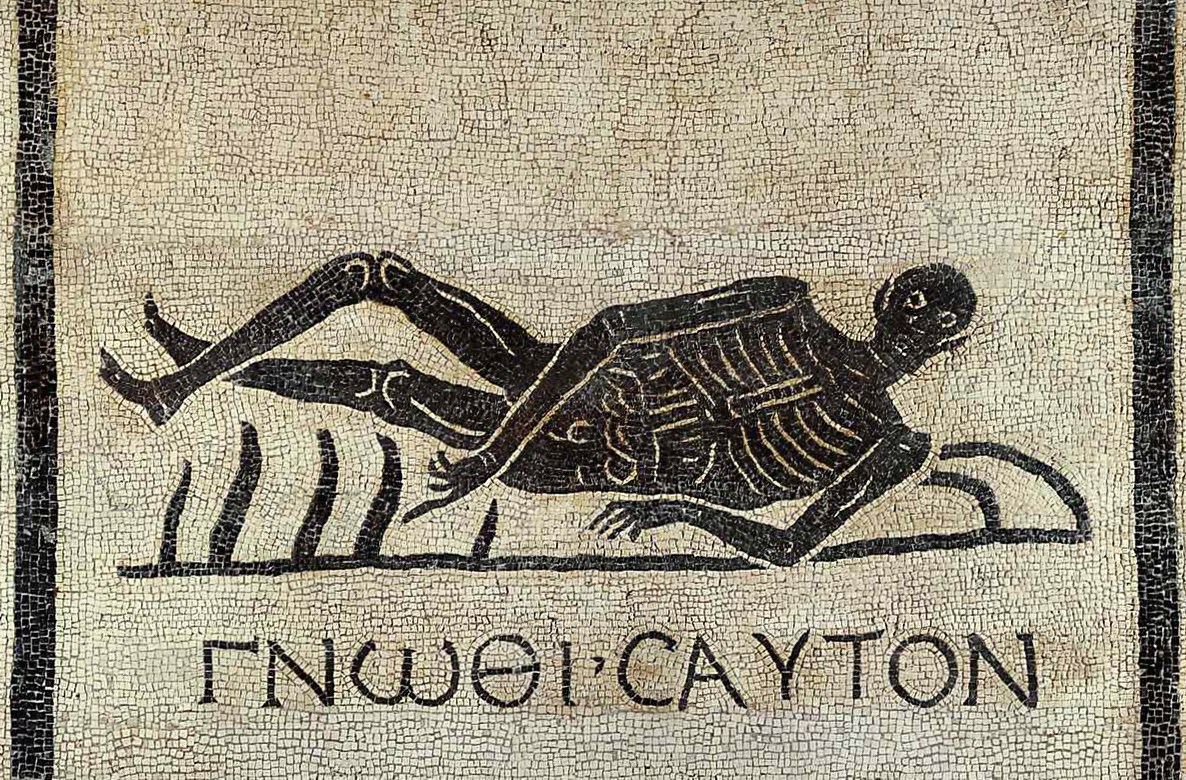

“Know thyself” is the dictum which appeared on the front of the temple in Delphi. But what does that mean and why is it important?

Presumably, it means to know, first and foremost, one’s own character and it is important because only by knowing one’s character can one be aware of one’s limitations and avoid likening oneself to the gods. But, more simply, it is only by knowing one’s character that one can try and improve from a moral point of view, or make the right decisions in one’s life.

Centuries have gone past and one important addition to that Delphic injunction has come from the discovery of the unconscious. Again, it looks as if it is only by knowing our deep-seated feelings, desires, beliefs and intentions that we can actually improve our lives.

Thus, if you start approaching the issue from the Delphic injunction, there seems to be a certain distance between each subject and themselves. One’s character is not only what we manifest in acting and by living as we do, but it is also an object for each of us to study and make sense of, as if alien.

In fact, it consists of one’s dispositional mental states, let them be conscious or unconscious, which are the object of what, in The Varieties of Self-Knowledge, I call “third personal self-knowledge”. That is to say, in order to get knowledge of those mental states, we need to engage in quite complex epistemic procedures that have no guarantee of being successful. In fact, they are broadly akin to the ones we use to gain knowledge of other people’s minds. Yet, when successfully executed, these procedures give us substantial knowledge of ourselves. They give us knowledge that is sometimes difficult to attain and which is valuable because it discloses to us important truths about ourselves, on the basis of which we can eventually make decisions that can actually improve the quality of our lives.

Still, there is an important difference between the application of these epistemic procedures in one’s own case and in the case of other people. Namely, often times, in our own case and in our own case only, the prompts we have to start with are inner feelings and other occurrent mental states we are immediately aware of. That is, mental states we are aware of in a “first-personal” way.

The overarching claim of The Varieties of Self-Knowledge is that a comprehensive account of self-knowledge should be an account of both first- and third-personal self-knowledge. Oddly enough, the contemporary debate on self-knowledge has tended to be oblivious to this rather obvious desideratum. On the one hand, behaviorists, for instance, have tried to reduce all of self-knowledge to third-personal self-knowledge. In a similar vein, contemporary cog.sci.-informed philosophers, like Peter Carruthers and Eric Schwitzgebel, have tried to deny the existence of first-personal self-knowledge drawing on recent empirical data, which show how ignorant or positively mistaken we can be regarding our own minds. Contemporary proponents of an inferentialist conception of self-knowledge, like Quassim Cassam, have tried to diminish the role of first-personal self-knowledge by arguing that at most it would give us knowledge of rather irrelevant mental states – like feeling pain in one’s foot right now. By contrast, in his view, important truths about oneself could only be revealed through inference to the best explanation starting with the observation of one’s own behavior and inner promptings. While I do agree that the latter kind of knowledge is certainly more interesting, it should be recognized that it would simply be impossible without knowledge of one’s occurrent mental states. Furthermore, while certainly not revelatory of one’s character, one’s first-personal knowledge of one’s own bodily sensations like pains, for instance, clearly serves an invaluable role. It is only that way that we can avoid certain dangers and set forth eradicating their causes. Finally, although a case can be made, based on empirical findings, against the width of first-personal self-knowledge, this does not mean that it is vanishingly small.

On the other hand, if one looks at the purely philosophical literature on self-knowledge, which has developed in the last fifty years or so, one will be struck by quite the opposite phenomenon. Namely, an enormous amount of attention has been devoted to first-personal self-knowledge with very little work done on third-personal self-knowledge. Why so? Well, because of what I would call a kind of philosophical snobbery. Let me explain. Since at least Descartes, philosophers have been puzzled by the characteristic traits of first-personal self-knowledge. For our minds seem to be “transparent” to us. Whatever is occurring within them, it seems immediately evident to us. The painful or pleasurable sensations I am feeling right now are “self-intimating”. If I am feeling pain in my foot, I am immediately aware of it, and if I have the relevant concepts, I can immediately self-ascribe that sensation. Conversely, if I do so ascribe it, unless there are reasons to doubt of my sincerity or of being cognitively well-functioning, the self-ascription is guaranteed to be correct. We therefore appear to be “authoritative” with respect to our own mental states. Since, however, such knowledge is not independent of experience, nor is it based on an observation of our own mental states, through something like a mental eye, or on the observation of our own behavior and on the inference to its likely cause, we seem to be confronted with a serious epistemological problem. How does that knowledge come about and how can it exhibit those traits, which seem to set it apart from all other kinds of empirical knowledge we have—that is, transparency and authority? The difficulty of making sense of this epistemological problem has led many philosophers to discard third-personal self-knowledge as philosophically uninteresting, because they have always ultimately considered it just one more instance of knowledge based on inference to the best explanation.

Indeed, some contemporary theorists, like Richard Moran, have gone so far as to argue that it is only when we deliberate what to believe, desire and intend, based on weighing reasons, that we are actually capable of first-personal self-knowledge. While in all other cases—that is to say, in those cases where we gain knowledge of ourselves through third-personal means and, interestingly, also when we make self-ascriptions of occurrent sensations—we would not be operating in that mode and there wouldn’t be anything epistemologically distinctive.

Again, I do agree that there is something epistemologically puzzling about first-personal self-knowledge and that it is a phenomenon in need of philosophical explanation. Yet, third-personal self-knowledge too is epistemologically interesting, once one realizes the variety of methods by means of which it can come about, over and beyond inference to the best explanation. Moreover, while I do agree that there is definitely something distinctive about our knowledge of what I would call our “commissive propositional attitudes”, I do think that self-ascriptions of sensations are also a manifestation of first-personal self-knowledge, even though, as we will see, they do call for a subtly different account than the one we might want to give for our knowledge of our commissive propositional attitudes.

I believe that historians often interpret “Know Thyself” as “know your place in the scheme of things – where you fit in society.”

Maybe so. Originally it was meant to remind humans of their limitations.

The dual approach that that Annalisa Coliva recommends, which allows both first-person and third-person routes to self-knowledge, seems to me very sound indeed. Often in spite of all the external “third-person”) evidence we can know (n.b.) what is going on with us, by some small but persistent and closely-held private insight. On the other hand, a whole world of private personal insights can be rotten and fall apart at a word or two from a friend or someone who knows us, and is perhaps a little unsympathetic. I am moved to wonder whether there isn’t such a thing as “second-person” knowledge. This would be the same as third-person knowledge in Coliva’s sense (which seems to be a matter of method as well as available data), but differ in regard to the relationship to the one known of the knower. “You” is different from “She” and “He”. There can be an element of accusation, say, or a compliment and a celebration, or a confrontation, which you don’t get in third-person style reports. I am thinking of Tolstoy’s account of sharing a room with his older brother, both now grown men, and Tolstoy kneeling by the side of the bed as he had done since childhood, to pray, and his brother looking at him and say, ‘You don’t still do that, do you?’ Tolstoy reports that at that moment his childhood faith collapsed. He had not himself known that his faith had been dead for a long time, but his brother knew. This is the sort of perhaps confrontational thing thing I had mind as “second-person” knowledge parallel to Annalisa Coliva’s other two senses.

Coliva recognizes the epistemological problem about first-person self-knowledge. How do I know that I am feeling uneasy, say? I wonder whether she would share with us any insight she has into this problem. Sometimes I think of it like this. There is the first-person state, uneasiness, over in the left-hand corner. In the right is me, doing something called “feeling” the state. Now is this like a person feeling a bolt of cloth, say, or feeling the texture of a coat? And if so, what is the perceptual system, the mechanism by which we do it?

That’s great Jonathan! I do think there is third-personal self-knowledge based on testimony. More on that in the next post.

And indeed I will say more about my views about first-personal self-knowledge in the third one.

I will also say more about the way in which we can get to know ourselves through the interction with others and even through literature and movies.

How would I realize that I am feeling uneasy, say? I ponder whether she would impart to us any knowledge she has into this issue. In some cases I consider it like this. There is the main individual state, uneasiness, over in the left-hand corner. In the privilege is me, accomplishing something many refer to as “feeling” the state. Presently is this like a man feeling an electrical jolt, say, or feeling the surface of a coat? What’s more, assuming this is the case, what is the perceptual framework, the component by which we isn’t that right?

A lot seems counter-factual and ridiculous

Brainology

A philosophical position of very great interest is seond person knowledge about ourselves, a knowledge that is neither equal to first person knowledge of ourselves or to the third person point of view.

Instead of discussing this, my point of view is that we can learn much about ourselves and others by studying the second person access to ourselves.

Correction…nor to the third person point of view.

Thanks Olav. If you prefer to call self-knowledge based on testimony second-person self-knowledge, no problem. What matters, anyway, is the fact that testimony is a source of self-knowledge. More on this in the second post, which is now out.

I understand:

Stimuli to brain reveal states of mind which can be identified as in two parts.

1.A mental state (correlated to brain state)in its feelings,emotions & dispositions.These are all based on neuronal reactions.

These are first- personal traits and

2.A mental activity (Correlated to brain activity)related to stimuli and neuronal reactions.

The mental parts correlated to neuronal reactions is the present interacting self.We can call them mental reactions to stimuli.

We can know the mental state in a higher level consciousness directly.The lower level consciousness is capable of knowing the

activity portion.Our character can be known indirectly through several observations of behaviour,indirectly.These are third-

personal traits.

Thanks for the comment!

I do not talk about brain activity. I do not think we can directly know brain activities as such. My book concernes only mental self-ascriptions, whatever their realization might be. In the third post, I will address the issue of first-personal self-knowledge. But yes, you are right that I think we can know our own mental dispositions in a third personal way, using a variety of methods, which I’ve briefly presented in the second post.