In standard approaches to folk psychology, our folk psychological reasoning is taken to be a species of causal reasoning. And while there is some attention to other kinds of reasoning in the developmental literature, notably teleological reasoning, most of the research I’ve run across on children’s social reasoning and explanations are also put in terms of causal reasoning. But given my take on explanations as offering justifications for behavior, I’m really interested in investigating the role, evolution, and development of normative reasoning, or seeing the world through a normative lens.

Lately I’ve been thinking that social minds may, in general, have an ability to engage in reasoning about how others should act. I call this normative sense naïve normativity. I’m developing an idea of Hannah Ginsbourg’s whose notion of primitive normativity refers to a kind of normativity that can be had without recognizing rules, but is had by those who have the appropriate experiences, have the motivation to “go on” from that experience in the right way, and experience some sense of appropriateness when engaging in the proper action (Ginsborg 2011). Her primitive normativity rests on understanding oughts or appropriateness without requiring the ability to articulate that understanding, and without the need for language or metacognitive abilities. For examples, a child demonstrates primitive normativity when she sorts red blocks from blue blocks into two distinct groups.

I like the block example because it illustrates the notion of belonging, which is perhaps the most primitive of normative notions. Konrad Lorenz noticed it in young goslings who acted as though they belonged with whatever creature they first saw after hatching. An imprinting mechanism allows many species to easily solve the belonging problem, and fulfills Ginsborg’s criteria for primitive normativity (assuming the appropriate consciousness response in the goslings). Lorenz’s graylag goslings, who first saw him after hatching, imprinted on Lorenz and followed him around as if they belonged with him. These goslings had the right kind of experience (they observed Lorenz in the critical period about 13 hours after hatching), they had the innate disposition to respond to that experience in a certain way (the imprinting mechanism), and we may surmise they had the right kind of affect—calm and even comforted around their human “mother”, and upset when separated.

I suspect that the child’s ability to sort blocks is based on an earlier recognition of social belonging, much like the hatchlings’ ability to realize that they belong with the creature they imprint upon. Social belonging is a basic kind of ought, which we can formulate as an understanding that I go with these people here rather than those people there. Naïve normativity is the capacity to think about how we do things around here. It adds to Ginsborg’s notion the ability to distinguish in-group from out-group members; there is the we of how we do things around here, and there is the way we do things. So engaging in naïvely normative reasoning requires in-group identification as well as identification of proper behaviors of the in-group. Human infants are great at discriminating their most important in-group member. They are able to recognize and distinguish between their mother’s breast and that of another lactating female (Cernoch & Porter 1985; Macfarlane 1975; Russell 1976), the mother’s face (Sherrod 1979; Walton, Bower and Bower 1992) and voice (DeCasper & Fifer 1980, Fifer 1987; Standley & Madsen 1990). The multimodal recognition of the mother is a key aspect to the sense of belonging to that individual rather than to another. The ability to recognize who one belongs with early in infancy facilitates the ability to learn culturally specific behaviors, and leads children across cultures to quickly show large differences in habitual behaviors such as sleeping, toileting, artifact use, or eating. Among industrialized societies the differences are often small, but when comparing industrialized to small-scale societies, the norms surrounding these sorts of early developing cultural behaviors are stark. (I really enjoyed Meredith F. Small’s Book Our Babies Ourselves on this.)

Naïve normativity is an understanding of the way we do things around here that does not depend on conformity to an antecedently recognized rule. While we can later extract rules from our normative practices, the rules are not needed for the development of the normative practices and the expectations that community members will practice these cultural behaviors.

This early understanding of naïve normativity is related to the infant’s early sensitivity to intentional agency. In-group members are agents, they behave in certain ways, and these are behaviors to aim for. So, agency understanding is tied up with naïve normativity. This is going to be especially true when the in-group members are cognitively flexible, and can respond differently toward the same set of stimuli. So I’ve been playing around with variations on this argument:

- Cognitively flexible behavior is not directly caused by observable environmental features.

- So, the ability to anticipate cognitively flexible behavior cannot be an example of simple causal reasoning.

- Instead, this ability is either an example of complex causal reasoning, or it is an example of normative reasoning.

Complex causal reasoning might look like a theory of mind. The normative reasoning, on the other hand, is a case of matching the situation to the group norms and expecting the target to do what she should do considering her role in the group.

Naïve normativity may be central to human social cognition without being unique to humans. If normativity is an early-developing and foundational cognitive ability that is necessary for social interaction, and if it is unique to humans, then there are downstream consequences for other capacities that may also be unique to humans. But if we share this basic sensitivity with some other animals, there is a challenge to some uniqueness views that are currently on the table. Lori Gruen and I wrote a book chapter “Empathy in Other Apes” that appears in Heidi Maibom’s collection Empathy and Morality out this year with OUP. In the chapter we discuss some of the norms that other apes might be sensitive to—from protesting infanticide to helping others cross the road to dismantling poacher traps. Acting according to norms, and expecting others to act according to norms doesn’t need to make you a moral agent. But there may be evidence of another kind of agency in other animals, and that’s what I’ll post on next!

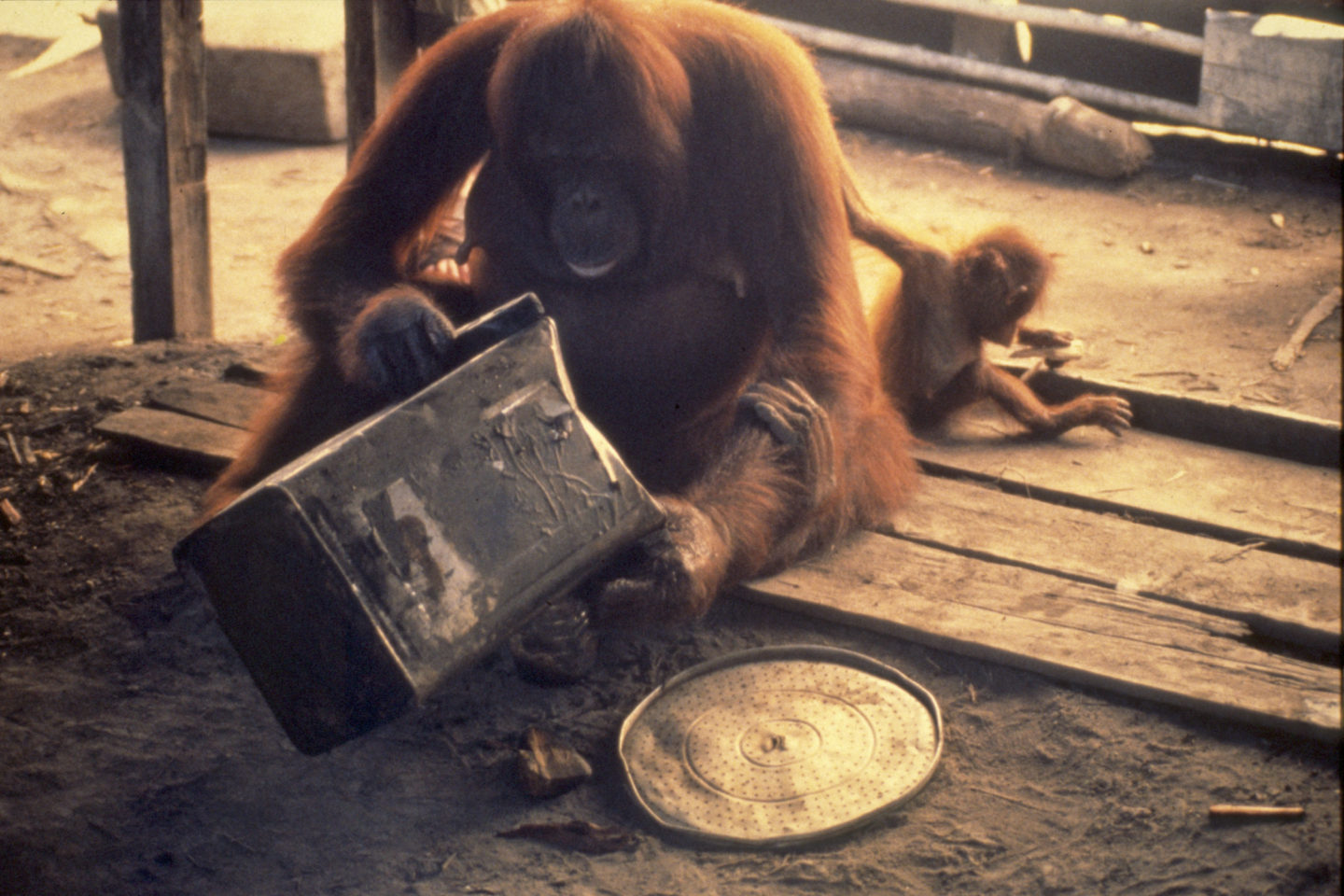

Note: The cover photo is by Anne Russon. At Camp Leaky, she observed lots of cases where orangutans seemed to think that humans are their in-group. In this photo, Supinah is imitating the behavior of the cooks, filling the stove with fuel. Notice that her infant is looking on.

Hi Kristin,

I like the example of children sorting things as a naive form of normativity. My 14month old likes to push his smaller toys inside his snack container. He gets really upset when you try to get the toys out of the cup. It is as though his toys are supposed to go inside the container.

I agree with you that agency understanding and naïve normativity are bound together. But I have a quibble with 1) in your argument. A behaviour could be directly caused by the environment. But it could still be cognitively flexible, say, if my desire not to behave in that way could override the causal link. I think reflexive saccades might be an example. Your eyes normally turn as the stimulus in the periphery lights up. But that’s a response you can withhold if you are asked to remain at fixation point.

Anyway, I think this is a smaller point. But I thought I would ask about it to see what you thought. Am I right? Do other variations of the argument depend on something like 1)?

Thanks!

Hi Santiago, thanks for your example. But I’m not sure I get it. Does the case work like this: when I desire to not engage in an action that would be caused by the environment I choose not to engage with the environment in the way that causes the effect (I focus on a reference point that doesn’t cause the saccade effect)? If so, isn’t that just two inflexible responses to two different aspects of a larger stimulus, and the agent chooses which aspect of the stimulus to attend to. Or am I missing something?

Hi again Kristin!

Would you invoke this notion of naive normativity to explain Kiley Hamlin’s findings regarding infant *moral* judgment (preference for helpers over hinderers, preference for publishers of hinderers, preference for attempted helping over accidental helping, etc) ? If not, what do you think are the earliest signs of naive normativity? Is this going to be an innate feature of cognition, like the gosling’s imprinting, or can it be learned somehow?

*punishers, not publishers. Lousy autocorrect!

Hi Evan, Yes totally! In my talks on this topic I offer naive normativity as an alternate explanation to the “moral glimmering” interpretation. And I was first talking about it being innate, but after talking with some anthropologists it seems this might be learned very early. For example, early interactions between mother and infant on the breast might be an example of developing naïve normativity, when the infant stops suckling and the mother jiggles the baby, the baby resumes eating. Apparently this interaction is seen across cultures and is one of the earliest signalling between mother and infant. The infant comes to realize that she should continue suckling when jiggled. So maybe it is learned, but only very early on. I’m not sure about that.

Not sure. Perhaps, I am the one missing something, or maybe presupposing too much.

I assumed that a cognitively flexible behaviour was one that could be shaped by cognitive states. The reflexive saccade can be prevented by my desire not to move my gaze. That would make it flexible. However, the reflexive saccade is an (example of?) environment-caused behaviour. If I don’t make an effort to stay put, the stimulus triggers the eye movement.

You say in the reply that this is a case of choosing between two inflexible responses (saccade vs. eyes on fixation ). This makes me think that you mean something different (stronger) by “cognitively flexible” behaviours. Am I right?

If so, what do you mean by it?

Hmm…so is the reflexive saccade elimination caused by your desire not to move your eye, or is it caused by your decision to fixate on a point (which was in turn caused by your desire not to move your eye)? The example reminds me of the ethics of belief stuff–I can make myself believe that it’s dark in here by turning off a light in the nighttime, but that’s very different than willing myself to believe something when it isn’t the case.

My interest in cognitive flexibility is that given flexibility (which we can observe in different species), we can’t decide which behavior is going to come next just by looking at the situation. We need more. I want to say that what we need is a different kind of reasoning; not a causal reasoning but a normative reasoning. But maybe I’m reaching when I try to get there from flexible behavior…

Hi again Kristin,

I really love all of your points here! Just to be sure I understand, though, I usually think of practical inference as a kind of nexus of the causal and the normative. That is supposed to show something deep about the nature of practical rationality; if I am a rational agent, in this sense, I am motivated to do what I should do. (Presumably, none of us mean to limit this to ethical normativity, but neither do we want it to weaken into mere statistical normality. Right?)

Do you mean to pull this nexus apart when one agent is thinking about another from the outside–in the sense that agents sensitive to primitive normativity would routinely think that agents ought to do things that they are not causally disposed to do, even absent reason to think the agent is not functioning well (i.e. is not rational?). When dealing with other humans, I usually have an implicit assumption that plays the role of charity–I assume others are practically rational, so that they will be motivated to do what they are aware they ought to do. Is the point that, in terms of the evolution or development of these sensitivities, we should expect the normative to come before the charitable assumption of rationality, so that it won’t necessarily imply anything about the causal structure of the agent’s psychology?

Hi Cameron, interesting questions. I guess I feel like the standard FP folk do take social reasoning to be purely causal. Of course Dennett is an exception. And it really struck me (6 years ago now) when I was looking at the developmental literature and almost all the interest in explanations were on causal explanations. I discuss that in Chapter 8 of Do Apes Read Minds. A couple of examples: Callanan & Oakes take as causal the child’s question, “Mommy, I always ask why. Why do I always ask why?”, because they understand the mother’s answer, “Because you are curious about things” as stating the cause of the child’s behavior (Callanan & Oakes 1992). But do dispositions cause, or describe?

And when a child asks”Why [did the crawfish die]?”, and the parent answers, “Well, maybe he’s old” (Chouinard 2007, 103), Chouinard interprets the parent as giving a causal answer. But old age doesn’t cause death, rather it is associated with the diseases and decay that cause death. Finally, the question “How come I cannot go outside?” (Chouinard 2007, 17) is interpreted as a causal explanatory question, but might be a request for normative information.

So, yes, I do want to pull apart the normative and the causal. An agent with just the normative but not the causal might make some mistakes–maybe we could even get signature effects, if the agent doesn’t know that the target hasn’t gained the norms. (The target doesn’t have to be aware of operating according to or against the norms, when it’s only primitive or naive normativity.) But that’s all consistent with adult humans using the combination of normative and causal reasoning, no? Or do you see some problems on the horizon?

I don’t see any major problem on the horizon just yet–it just seems fundamental to my notion of an agent that agents are practically rational in this sense. But I’m not one to monger a priori roadblocks without some additional justification of empirical relevance.

You know, part of my shtick lately has been looking at debates in the animal cognition literature from the perspective of the naturalistic mental content literature; and maybe doing so here would illuminate some resistance people might have to your idea that nonlinguistic FP explanations should not necessarily construed as causal. There was of course a roughly isometric debate between Anscombe and Davidson in Philosophy of Action, and the whole tradition in naturalized approaches to mental content followed Davidson on this point. This may be why there’s a huge section of philosophers of mind who take for granted that FP explanations have to be causal, because the whole challenge regarding mental causation that people have been trying to solve since the 70’s doesn’t even arise if you don’t follow Davidson here (the major moves in recent philosophy of mind–Fodor’s computationalism, Dretske or Millikan’s teleosemantics, all being attempts to address this problem).

Now, these two issues might be conflated, as you note, by some theorist who thought that to attribute content as a philosopher of mind just was to deploy the very folk psychological system that one thinks one shares with apes. But without this assumption, I suppose the two issues could be considered orthogonal; one can perfectly well maintain that for the purposes of philosophy of mind we should take psychological explanations as causal in the relevant sense, but nevertheless hold that FP, especially nonlinguistic FP, does not in fact infer that agents are practically rational in this sense.

Cameron, yes I’m really sympathetic with all you’re saying here. I share your diagnosis of the current interest in causal explanations for action, as well as the worry that we’re doing different things as philosophers ascribing content and as folk engaging with other folk.

Fascinating stuff. The potential problem I see simply has to do with the problems pertaining to the normative more generally. Your argument implies that normative cognition solves problems absent causal information. Normative cognition is heuristic, which means it possesses some specific problem-ecology, that it is geared to solve a special set of problems–as is obviously the case with normative cognition.

Even ought has an ought. In a sense you’re mapping the developmental *ecology* as much as the processes of normative cognition. Very cool.

The problem is that you have already transformed whatever pretheoretical normativity amounts to into something theoretical as soon as you use traditional theoretical posits, normative vocabulary, to ‘explain’ naïve normativity. The question becomes one of whether the problem of normative cognition is a problem that theoretical normative cognition can solve. You could end up mapping yourself into a corner!

I sure don’t want to end up in a corner! It’s hard to know what vocabulary to use. Do you have a suggestion about how to talk about normative cognitive without transforming it into something theoretical? That would be very helpful!

Tough, tough question. This problem is endemic to all attempts to theorize the ‘naïve,’ ‘implicit,’ ‘pretheoretical,’ or what have you. Does glossing nonhuman social behaviour using normative concepts amount to an illicit anthropomorphization? I’m not sure what you can do short of taking a Davidsonian attitude, refusing to essentialize, indexing the adequacy of your normative apparatus according to the results it provides.

Since answering the question ‘What is normative cognition good for?’ is an important part of the puzzle of normativity more generally, the problem of misapplication, using normative cognition to solve problems it cannot in fact solve need not be a problem at all, so long as you have some means of recognizing misapplications. My hope reading research such as yours is always that I glimpse some clue as to the nature of the problems normativity is *actually adapted to solve,* as opposed to the kinds of problems philosophers are prone to throw normativity at (like the problem of ‘meaning’). If applying normative cognition actually helps you press in this direction, actually generates empirical results, then so much the better. Fighting is the only way to prove who has the stronger Kung Fu!

Anyone interested in the potential pitfalls of normative cognition in philosophical contexts should check out Stephen Turner’s wonderful, Explaining the Normative.

There are a variety of possible positions between inflationary anthropomorphism and deflationary interpretivism. The most plausible by my lights in the current contexts are to focus on the ways that animals can detect and respond appropriately to errors and then study the cognitive/neural mechanisms that enable these forms of sensitivity and flexibility. Whether or not you think such study can naturalize the relevant form of normativity itself, the systems that are so sensitive to normative facts are natural systems, and we can articulate empirically-informed differences between kinds of psychological mechanisms that do and do not reliably respond to them appropriately.

Errors, the fractures of cognition, can also help us answer RS’s question of what problem the capacity was adapted to solve. Cameron, in your reading of classical ethology did you find anyone interested in errors (especially considering them to be “fractures” of thought)? Noam Miller thinks he got this idea from that tradition, but in the last few months hasn’t been able to track down a reference. Maybe you know?

Kristin, nothing springs to mind, but it’s a very interesting question, but I’m not so well read outside the canon of classic historical ethological texts. (In general I think the ethological perspective expects that animal behavior will be very error-prone but that it will tend to be sufficient for adaptive purposes in evolved environments.) The general lack of emphasis on learning and cognitive flexibility in the classical ethological literature would seem to me to suggest that while they might have a lot to say about malfunction, it wouldn’t get at the kind of naive normativity you’re after. (For example, you might see how Tinbergen discusses a couple of “errors” here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/4509366.pdf?acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true ).

However, I’m also not sure I’ve come at that literature with this specific question, and it’s a very interesting one so I’ll let you know if I come up with something.

An exception of course would be Ristau, who was pretty sophisticated on representational issues. But the emphasis on errors and misrepresentation there might be more derived from Dennettian thinking than a novel perspective originating from the ethology itself.