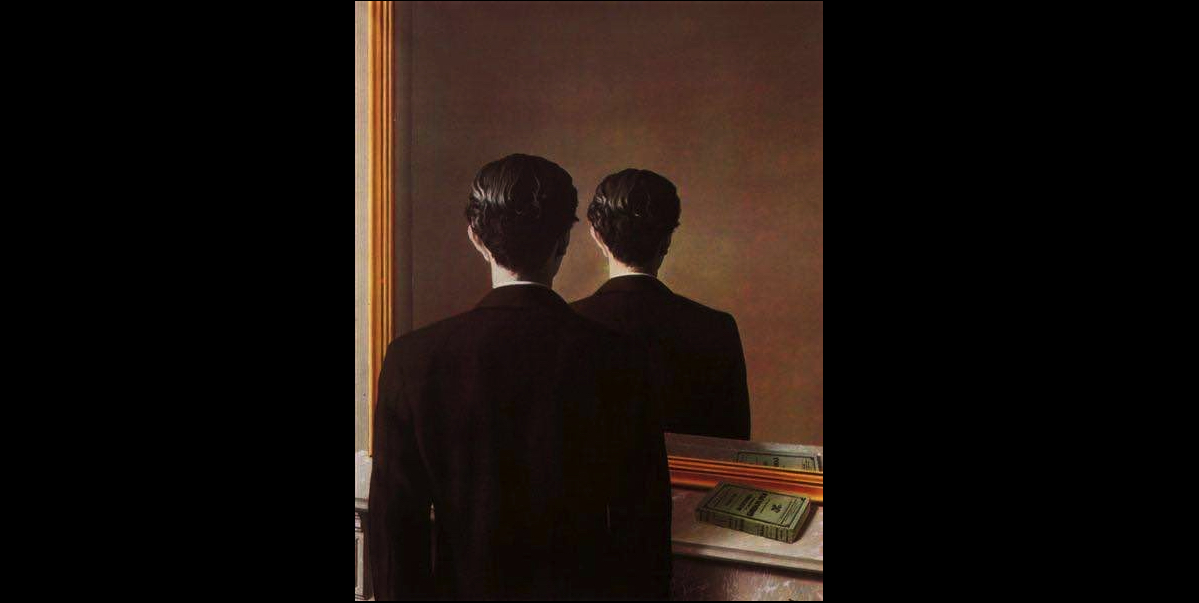

Remembering from-the-outside involves adopting a point of view that one didn’t occupy at the time of the original event. In this sense, the visual perspective of observer memories seems somehow ‘anomalous’. Here I articulate two related objections to genuine memories being recalled from-the-outside: (1) the argument from perceptual impossibility; and (2) the argument from perceptual preservation.

The argument from perceptual impossibility claims that because it is impossible to see oneself from-the-outside at the time of the original experience, one cannot have a memory in which one sees oneself from-the-outside: one cannot (genuinely) remember from an observer perspective. Relatedly, the argument from perceptual preservation holds that memory must (broadly) preserve the content of the previous perceptual experience. Even if we concede that the notion of exact preservation is too strict, it is sometimes suggested that genuine memory may lose content over time (through forgetting), but nothing must be added to the content of memory. Because observer perspectives seem to have an added representation of the self, a representation that was not available at the time of encoding, then, so the argument goes, they cannot be genuine memories.

Both these worries stem from a broadly preservationist view of memory. The general idea behind them is that the content that is retrieved from memory is not the same as the content that was encoded in memory. According to these two arguments, observer perspectives cannot satisfy preservationist conditions placed on the context of memory encoding.

The first step in responding to these arguments is to note that memory is inherently (re)constructive. Empirical evidence shows that memories are open to change, and that their content is not fixed at the point of encoding. Memory is a creative process. It is important to note, however, that (re)constructive processes operate at different points in the memory process. There are constructive processes that operate during memory encoding; and there are reconstructive processes that operate at memory retrieval. As such, I suggest that there are two ways of responding to the arguments from perceptual impossibility and perceptual preservation. First, by suggesting that observer perspectives are reconstructed at the moment of retrieval; second, to argue that observer perspectives may be constructed during perceptual experience at the time of encoding.

The first approach shows that the context of retrieval can affect the content of memory. Information that was originally encoded into a field perspective memory can be reconstructed into an observer image. One way of responding to the argument from perceptual impossibility is to say that observer perspectives are reconstructed when there is an evaluative, emotional, or epistemic gap that opens up between the past and the present (Goldie 2012). This occurs when what one now thinks, feels, or knows about a past event is different to what one then thought, felt, or knew about the same event. When such an ‘ironic gap’ opens up observer perspectives may be reconstructed. In such cases it is one’s present knowledge or emotion at retrieval, the way one now views the past event, that is driving the reconstruction of the observer image. This means that in order to see yourself in memory you don’t need to have seen yourself during the past event.

One may also respond to the argument from perceptual preservation by focusing on the context of retrieval. There are good arguments to show that the (re)constructive nature of remembering means that new content may be generated by reconstructive processes at (or before) retrieval. Because memory often, perhaps typically, involves the incorporation of information that was not encoded during the past event, genuine memories may involve the generation of content. Therefore, even if observer perspectives involve an additional representation of the self, they can still count as genuine memories.

Observer perspectives are often explained precisely by appealing to the reconstructive nature of memory at retrieval. Indeed, they are typically thought to involve more reconstruction than field perspectives, where the latter are understood to more or less preserve one’s original point of view on the event. Yet, given that there is sometimes an (implicit) association between reconstruction in memory and error or distortion (cf. Campbell 2014), this seems to leave us with a view that observer perspectives are somehow less accurate. As such, focusing on the context of retrieval in answering the objections to observer memories may not be completely satisfactory. Someone sceptical of observer perspective memories may simply conclude that reconstruction at retrieval still involves a degree of invention. If one says that memory is reconstructive and that new mnemonic content can be generated, then the sceptic can still reject observer perspectives because this additional content is a sign of false memory. And, even if observer perspectives are not thought of as outright false memories, they are still often seen as distorted memories because of the change in the visual perspective that occurs after the event.

In order to fully answer the sceptic’s concerns, and in order to better understand observer perspectives, one needs to look beyond the context of retrieval. A more complete understanding of observer perspectives, and hence a better understanding of personal memory, requires an understanding of how the context of encoding is important for the content of memory.

Memory is alive not only to the context of retrieval, but also to the various sources of information and the context in which the event took place. I suggest that, at least sometimes, the context of the perceptual experience can encourage us to adopt an external perspective on ourselves at the time of the original event. Thoughts, emotions, semantic knowledge, etc., which were part of the original experience, can be used to construct an image from an observer perspective. We can, in a sense, use this information to get outside of ourselves. This is not to suggest that such observer perspectives are memories of out-of-body experiences. You don’t have to literally see yourself during the perceptual experience in order to see yourself in a memory of that experience. Observer perspective memories are much more quotidian than this, and they are constructed from non-visual information encoded at the time of the original event. When you remember an event from an observer perspective you are not remembering seeing yourself at the time of the past event, you are simply remembering that past event. In this sense, field and observer perspectives are different ways of remembering the same past event.

The idea that observer perspectives can be formed from non-visual information at the time of the past experience is one that requires some cashing out. It requires an account of what it means for the self to be represented in memory from an external point of view. I turn to a discussion of these issues in the next post.