The claim so far is that it feels different when one is aware that a hand is one’s own and when one is not. Now one needs to explore this phenomenological difference and determine its nature. There are three ways to go from here:

- Bodily experiences represent only low-level sensory properties, on the basis of which one can judge that high-level properties, such as ownership, are instantiated.

- Bodily experiences represent high-level properties, but not of ownership, on the basis of which one can judge that ownership is instantiated.

- Bodily experiences represent the high-level property of ownership.

The first hypothesis is that the phenomenal contrast is exhausted by sensory properties. Let us go back to the RHI. When participants report ownership after synchronous conditions, they also experience referred sensations in the rubber hand and they mislocalize their hand in the direction of its location. One may then argue that these tactile and proprioceptive differences exhaust the phenomenal contrast. The general hypothesis is that the awareness of these low-level features gives rise to the sense of ownership. But how can it account for dissociations between the awareness of low-level and of high-level bodily features? For instance, some patients with somatoparaphrenia can experience tactile and painful sensations and yet lack a sense of ownership: “P: I still have the acute pain where the prosthesis is. E: Which prosthesis? P: Don’t you see? This thing here (indicating his left arm).” (Maravita, 2008, p. 102). There is no doubt here that the patient was experiencing pain and that he was locating his pain in his left arm, and yet there is also little doubt that he was not aware of his left arm as being his own. The sense of ownership is a positive quality over and above sensory features.

The second hypothesis grants that bodily experiences can represent some high-level properties but not the property of ownership. For instance, one might suggest that there is a phenomenology of agency, upon which the sense of ownership is derivative. On this new proposal, the sense of bodily ownership does not consist in agency; it simply depends on agentive feelings. Two pieces of evidence point to this direction. First, somatoparaphrenic patients are most of the time paralyzed and they often complain about the uselessness of their ‘alien’ limb. Secondly, amputees that have received hand-transplants experience their new hands as their own only when they feel that they can control them, and not earlier when they gain sensations in them (Farnè et al., 2002).

The difficulty with this new proposal is that it is not clear why there can be agentive feelings but no ownership feelings, to start with. Both involve high-level properties and if one rejects one, one may as well reject the other (as Bermúdez consistently does, 2010, 2011 for instance). Putting aside this worry, it is also not clear how the agentive proposal can account for cases of individuals who feel that they have no control over a limb and still experience it as their own (as in many cases of paralysis, in delusion of control, in the anarchic hand sign, and in the RHI). The agentive proposal can neither explain the fact that one can feel that one can move a limb and still fail to experience it as one’s own. This is clearly demonstrated by patients with somatoparaphrenia that are unaware of their paralysis: they erroneously feel that they can control their paralysed ‘alien’ hand, and yet they do not experience it as their own.

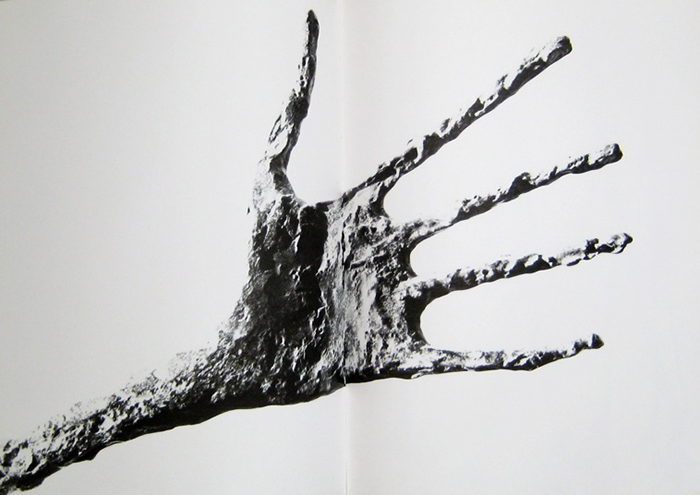

One can then propose that there is a phenomenal property of ownership, what one may call a feeling or an experience of bodily ownership. The question then becomes how to characterize it. In Mind the body, I propose that it consists in an affective feeling. To clarify what I mean here, take the example of meeting by chance a friend that you have not seen for a long time. When you see her, not only do you have a visual experience of the features of her face but you also have a feeling of familiarity, which results from increased arousal. This example shows two things. First, there can be more in perceptual awareness than sensory properties. Secondly, the personal significance of the well-known person is phenomenologically accessible, leading to a specific feeling. Likewise bodily awareness can include not only sensory properties, but also affective ones, and they can lead to specific feelings. The feeling of ownership involves a different type of significance than familiarity, what we might call an evolutionary significance. In brief, survival involves preservation of one’s body. This is why the brain evolved mechanisms to protect it, including dedicated processing of a margin of safety surrounding the body (peripersonal space) and a mental representation of the body to protect (protective body map). One might then say that the feeling of ownership is nothing more than the awareness of this value for the self. It individuates the one body that matters to me for self-preservation more than anything else.

This affective conception of ownership finds support in the empirical literature. On the one hand, when participants report ownership for a rubber hand, they affectively respond when a hammer threatens to hit it as if it were their own hand. On the other hand, patients with somatoparaphrenia (or other disownership disorders) show no autonomic reaction when their ‘alien’ hand is under threat. However, one should not believe that the body that one protects is the body that one experiences as one’s own. Since one protects many things besides one’s body and since one does not always protect one’s body, this view is indeed clearly untenable. Like any other behaviour, protective behaviours can result from complex decision-making processes, involving a variety of beliefs, desires, emotions, moral considerations, and so forth. All that the affective conception claims is that the feeling of ownership consists in the affective awareness of the unique significance of the body for the self, a significance that is biologically rooted.

I immediately thought of puppies and kittens chasing then biting their tails as suggesting that ownership is a model that is learnt over time and through movement (the rubber hand is so effective an illusion because it is not moving). Maybe the tail is not so strongly owned as a leg, though neither the anesthetised tail or leg post nerve injury last very long.

Isn’t this a case of not properly identifying a visual object? A puppy sees its tail; it doesn’t identify it as its own. A bit like John Perry’s famous shopper who is seen making a mess.

I know very little about tails but I assume dogs feel sensations in them. There should be visuo-tactile integration, which should preclude them from not recognizing the tail. By contrast, Perry had only a purely visual access.

Definitely, dogs have sensations in their tails (as you’ll find if you accidentally step on one). But I have always assumed that puppies saw a wagging tail and went after it on purely visual evidence, without using the counter-indications from tactile sensation. (I could be wrong, of course.) I think the more complex kind of confusion (i.e., visuotactile) is possible when you intertwine your fingers with somebody else’s. That is, you might misidentify which fingers are whose in this situation. (Or am I wrong?)

It may be relevant here to know that patients with congenital insensitivity to pain as well as animals raised in pain deprivation consistently show self-harming behavior. One possible interpretation is that they have less confidence in their sense of ownership toward their own body, and thus less urge to protect their body from harm. Self-inflicting injuries can also be conceived as ways to test whether this is their own body or not. Something like “if it hurts, it is mine”.