[[This is a guest post by Matt Faw, a filmmaker who together with Bill Faw is the author of a recent paper in WIREs Cognitive Science, “Neurotypical subjective experience is caused by a hippocampal simulation”. The post is a précis of their article.]]

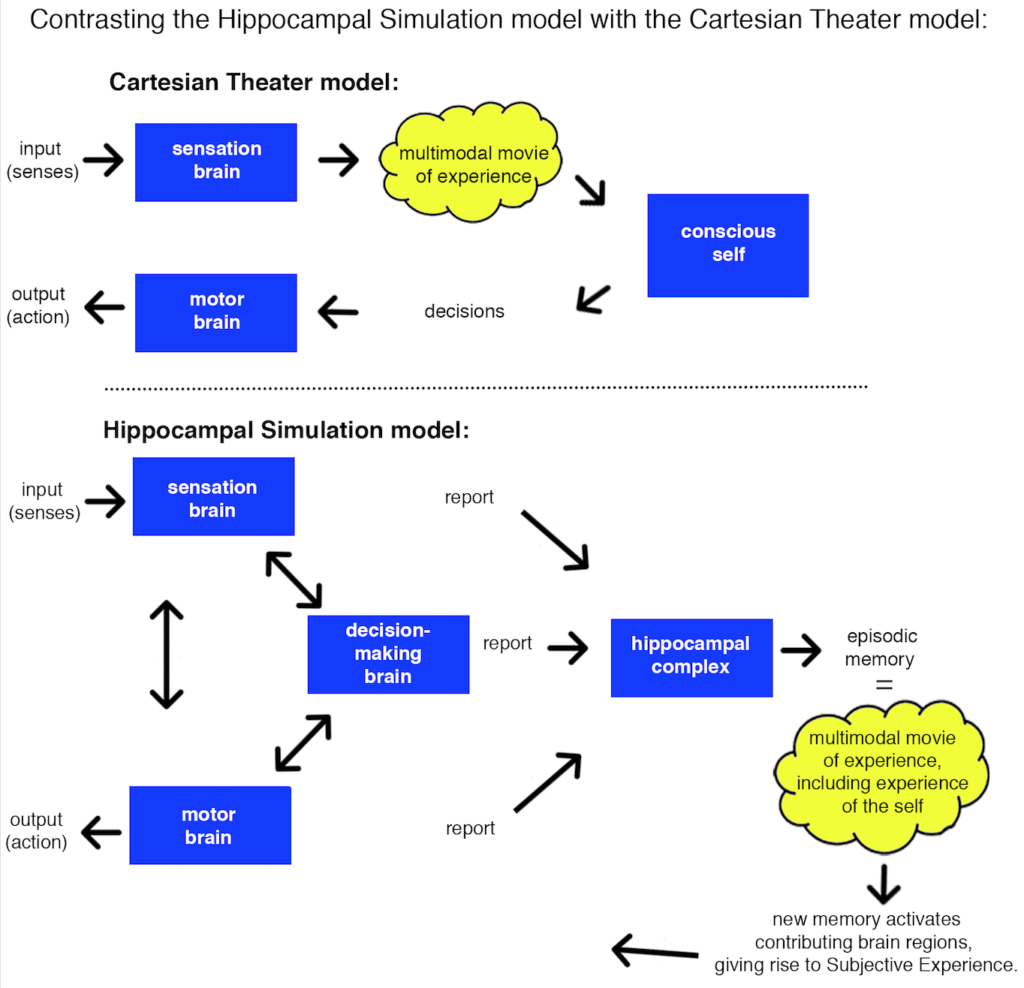

Consciousness. One of the problems in finding its neural cause is that the word itself is too ill-defined, and means too many things. Often, consciousness is postulated as a command-and-control process, an ersatz self that interprets sensory information, thinks about their meaning, imagines possible responses and their potential outcomes, decides the best course of action, and controls the body into behavior.

This definition of consciousness runs into conflict with the evidence of modern neuroscience. Brain imaging and pathologies reveal that brain processing is highly distributed throughout various structures, which we’ll call ‘nodes’. These nodes are semi-autonomous processing centers which work in parallel to each other, each taking on the most fitting part of any mental task. A robust communication scheme links various nodes into networks, and allows them to communicate with each other. However, no node or network of nodes is responsible for all the functions ascribed to consciousness in the paragraph above.

Another view of consciousness, first started by Immanuel Kant, questions whether the phenomenon is what it seems to be. From the 1st-person view, I seem to be a united perceiver / thinker / imaginer / decider, not a network of nodes. Perhaps that 1st-person view is inaccurate, an accident of evolution. After all, in dreams I also seem to be perceiving, thinking, imagining and deciding, even though none of those semblances are accurate to what my sleeping organism is doing. Both waking and dreaming feature this internal experience of being a self in the world, so maybe the experience is misleading. Maybe experience is a story that my brain tells itself, a form of mental movie that strategically depicts a unified mind and body, interacting with the real world, even though that united mental self may be a fiction.

Indeed, the current commonly-agreed upon philosophical definition of consciousness is just ‘subjective experience’ or the inner moment-to-moment virtual-reality movie of being a mind and body in the world. It is the working definition of consciousness, because although we can all agree that the appearance of an inner self is compelling, there is not yet evidence to suggest that the appearance is correct. Neurotypical subjective experience (NSE) is what our theory sets out to explain.

Given this limited definition of NSE – the inner appearance of being a mind and body in the world – we believe that definition suggests a strong candidate for how and why NSE exists in the brain. After all, we already know of a brain network that builds an experience of being a mind and body in the world. That network is the hippocampal formation (HF), which generates episodic memory.

Subjectively, we already recognize that episodic memory is a form of inner movie which, when recalled, closely resembles the original experience. This is especially true, immediately after a salient event, when it is possible to re-experience that event in vivid detail, including thoughts and feelings.

It has always been assumed that episodic memory occurred downstream of consciousness, and just recorded what consciousness was already processing. However, studies of the HF reveal that it is the one place in the brain where the entire experience comes together. The HF is at the apex of a ‘pyramid of reports’, multiple parallel processing hierarchies within which granular input is refined into increasingly meaningful conclusions. The salient final conclusions from each processing hierarchy are sent as reports to the HF, which binds those reports into one simplified but highly contextualized inner movie of experience.

We hypothesize that the inner movie of episodic memory is then shared around the brain, for error correction, to drive predictive processing, and to share one common story of ‘what just happened’. It is the activation of target regions by the brand new memory that we believe gives rise to the sense of experiencing.

We analogize this process to a news media outlet, receiving newsworthy reportage from all around the brain, stitching those reports into one simplified but contextualized ‘news report’, and then broadcasting that master report back around the brain, for a global experiencing of the big picture. Of course, no part of the brain is ‘watching’ the news report; rather they are activated by the new memory, and that activation gives rise to experience (just as the visual cortex does not ‘watch’ the outside world, but is rather activated by it).

This is a very brief outline of the mechanism by which NSE is generated, according to our theory. For the sake of brevity, we have left out large sections of the argument, particularly how the reports of both the body and the mind are generated, and included in the brand new memory. In our paper, we also deal with H.M. and similar patients with adult-onset complete bilateral hippocampal damage, investigating how they function without NSE. We briefly explore some mysteries of subjectivity, like dreaming, anosogonosia, alien hand syndrome, language and image thought, etc. and try to show how they may be explained by the model. Plus, we make a much more thorough anatomical argument for how sensory data becomes coupled with conceptual models and joins environmental models within the HF for the sake of memory generation.

Since we cannot encapsulate the entire argument in this blog, we encourage interested readers to seek out the original at the publisher’s site (currently not behind a paywall): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/wcs.1412/full or the same text at the authors’ site: https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B-3NAbdjTZEIOU5yc2s3OG5xam8

In conclusion, the mysteries of neurotypical subjective experience may be less mysterious than we’ve thought. We already know about a system which receives final conclusions from all around the brain, and which generates an inner movie of being a mind and body in the world. We already know how this inner movie can trigger a global brain experiencing (as in memory recall). The only inhibition to understanding how NSE is created in the brain is our intuition that the perceived self is the true agent of the brain and that the perceived mind is the actual cognition of the brain. If we are able to accept that the self and the mind are not what they seem to be, but are rather news reports from various nodes, stitched together into the overall gestalt of experience, then we can accept that NSE is caused by a brand new episodic memory, output from the hippocampal formation.

[[Questions about this theory can be addressed to the lead author, Matt Faw at: mattfawfilmmaker@gmail.com. More information about the documentary we’re producing is available at consciousness3d.net.]]

Theories of consciousness [C] that tie C too closely to memory formation tend to get wrecked on the rocks of patients like HM. I see you tried to deal with these patients, but it seems a bit unclear what your account is an account of, once you allow HM in the door.

I have never seen it suggested that he (and similar patients) lacked C. While he couldn’t form new episodic memories, he did have decent ability to speak, perform perceptual psychophysics tasks, recall older episodic memories (e.g., of childhood roads), and could form new procedural memories.

It isn’t clear what is ‘neurotypical subjective experience’ other than an experience of what seems to be happening right now. This can be made a lot *less* typical with various types of brain damage. But the main way to truly wipe out subjectivity, to eliminate subjective content altogether, is to do damage to the brain stem reticular activating system, which seems, by my lights, to be a better candidate for the core functionality of consciousness (as discussed by Piccinini here: https://philosophyofbrains.com/2007/01/06/consciousness-and-the-brainstem.aspx). And the specific (sensory) contents are provided by various thalamocortical loops for the specific sensory areas. So you can eliminate specific contents by (for instance) damaging V1. Obviously it’s more complicated than that (I’m leaving out attention for instance), but that’s the rough picture in my mind.

The hippocampus is clearly very important for the construction of episodic memories, which are (admittedly) crucial for forming a sense of self, offloading the memories off to the cortex. So, does disrupting hippocampal function disrupt things a lot? Yes, for sure! But not so sure it gets at the C core.

Note: when researching this I did stumble upon this interesting article on dreams in bilateral hippocampal patients (Torda: ‘Dreams of subjects with bilateral hippocampal lesions’). It’s very old-school neuropsychology, with a weirdly Freudian bent, and I haven’t found a good update.

Hi Eric, thank you for your comments. As you probably guessed, H.M. is the most common objection to our theory. We focused all of section 5 of the published paper on dealing with him and similar patients, but I will try to summarize here.

The primary distinction is in the various definitions of the word “consciousness”. From the third-person perspective, if you say a person is “conscious,” it can mean awake, attentive and responsive, none of which functions include the definition of “subjective experience”.

We should not assume that because the word has meant all these functions, that these functions therefore belong together, as part of a singular phenomenon. These various functions are largely attributable to distinct brain structures, like visual and auditory cortices for sensation, motor cortex for responsiveness, claustrum for synchrony, body state structures for feeling, and as you say, brainstem for overall arousal. No structure will ever be found in the brain that is responsible for all the functions implied by a third-person meaning of ‘consciousness’.

That is why the target phenomenon I’m trying to explain is not ‘consciousness’ per se, but ‘subjective experience’, and especially subjective experience among neurologically-intact people, which we’ve shortened to NSE.

NSE represents a story of a bodily and cognitive ‘I’, interacting with the world. This appearance of this ‘I’ is very compelling, and so consciousness is assumed to fulfill all the functions of that ‘I’, like thinking, imagination, decision-making, etc. However, like Kant and Metzinger and various other representationalists, we believe that the self that is perceived within NSE is not actually the thinker, imaginer, decider. It is just a news story about what the various brain nodes are doing.

The various nodes which are responsible for these various cognitive, sensation, and bodily functions all send their final ‘newsworthy’ reports to the hippocampal formation, for the sake of generating one unified, contextualized inner movie of ‘what just happened’, which can be re-experienced later for offline learning. This movie represents elements like arousal, sensation, imagination, etc. and so we subjectively misinterpret it as being responsible for those elements.

Memory is formed downstream from these various functions, and is not needed for them to work. H.M. still has all the brain regions responsible for arousal, sensation, feeling, and even imagination, and so of course we would say (from the 3rd person point-of-view) that he is ‘conscious’. None of those visible functions, however, are about the phenomenon we are trying to explain,NSE, which cannot be observed from the outside. We are only saying that H.M. lacked memory (and thus the NSE which arises from it), but that should not prevent him from being able to sense and respond to the world.

Nor are we saying that H.M. is ‘not aware’, even though NSE seems to be equivalent to ‘awareness’. Awareness really happens on the nodal level, as the various nodes interpret sensory data into meaning. However, it is only in the hippocampus that all the nodal awareness becomes stitched together into an enduring global movie of experience. That movie includes an ‘I’, which is needed for context (we need to remember who did what in an event for the memory to be useful), but that perceived ‘I’ is just part of the movie of memory. It is not who we actually are. We are the whole brain, but we only remember the memory movie of the memory self. Experience seems to be equivalent to awareness, because it is the only part of awareness that endures.

I hope this helps. Please let me know if you’d like some further clarification.

I’m not sure why cases such as HM lead us to reject a hippocampal basis for ‘consciousness”. The idea being proposed is that subjective experience is a memory and thus our awareness of events succeeds the actual events themselves. That is, our brains process input and so on and issue motor commands without awareness at all, but a moment later generate a pared down version of this for purposes of delivering a summary of what just happened and to help in ongoing predictive processing.

In other words, NO-ONE is actually “conscious” of what they are doing as they do it, although the time gap between actual events and the memory (or NSE) would be in the order of hundredths or tenths of seconds I guess, so it wouldn’t be apparent to us. Cases like HM simply illustrate that a human being can still function without the memory formation that we call NSE. In other words, HM could speak, learn new skills, retrieve older memories and so on because it wasn’t those functions that were removed. Rather, it was his capacity to generate an ongoing simulation of the sequence of events that is afforded by memory formation.

Looking at the example of damaging the reticular formation, or even say anaesthesia, we are making the assumption that these kinds of inhibitions are affecting consciousness itself. However, if this theory is correct, the effect is of causing the brain function to be impaired and thus there is no information to be passed to the hippocampus for incorporation in memory (and hence NSE).

Thank you, Graeme. Yes, that is very much what I’m saying.

What does H.M. stand for?

Hi, A brain. H.M. is the confidential patient acronym that was given to Henry Molaison, a patient who is famous in memory studies. Due to his extreme epilepsy, he was subjected to experimental surgery, ablating his entire hippocampus and amygdala and some surrounding areas. That surgery left him with extreme amnesia, of a precise kind. He still had access to information and skills that were encoded in the neocortex, but he lacked the ability to recall episodic memories (meaning the memories in which you re-experience aspects of an event that previously happened to you).

Because H.M., who lacked a hippocampus, was responsive and able to conduct normal conversations, it is assumed that he was “conscious” (as defined from the 3rd person perspective), and therefore the hippocampus could not be the seat of “consciousness”.

Hi Matt, Great essay and comments. I would say that H.M.’s case proves that consciousness as awareness is all over or distributed throughout the nodes of his brain. The absence of the hippocampus and amygdala denied him the ability o fully integrate much as an Alzheimer’s patient has awareness but cannot fully integrate memory and emotional attachments etc.

Thanks, vicp, for your response and for taking the time to read the blog. I agree that awareness must happen at a sensory nodal level (as response to stimulus from the sense organs), because that awareness is the very job of those nodes. If a visual node is destroyed in the brain, then downstream experience is still generated, but without the awareness information which that node should provide. Of course, the nodes, by themselves, cannot form a global awareness, which is why we say the hippocampus acts as the ‘news media outlet’ of the brain, stitching together nodal awarenesses into one global episode of a mind and body in the world. I believe that the reason why we, as organisms, are aware only of the hippocampal end-product, is that if both nodal and global awarenesses were experienced, the brain would be very confused and noisy, always living in a continual echo of semi-competing awarenesses. Instead, global awareness represents only the ‘newsworthy’ (i.e. dynamic, changing and surprising) stimuli, and the stereotypical processes of the brain, like body management and language formation, are largely left out of experience (unless things go wrong).

And yes, agreed, that the hippocampus is primarily an integration organ, evolved first to put together a big-picture event of all the salient brain processes, for later off-line learning. As you point out, the prefrontal cortices also are integration organs. My understanding is that they integrate information from earlier in their respective hierarchies, in order to arbitrate between conflicting interpretations and decisions. In both the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, recursive pathways help those organs predict what will come next, and those predictions help shape the information flow that is sent to them.

Let me know if you have any questions about the theory and its implications.

Well, I’m not english so forgive me if I have not understood precisely what you mean and if my english is bad, and also I’m not a philosopher so maybe I won’t use the good words. But, I don’t understand what is the problem with consciousness except what we want to do with it (as a human thing), to feel oneself responsible when breaking the law for instance. I think what you write here is surely OK, but it seems much more simple to me.

If you take a cat, it is self-conscious of what he is doing, it wouldn’t be able to climb to a tree if it didn’t know where are his legs in the space. So when we talk about human being, that’s not what we called consciouness, it’s much more the thoughts we have at the moment. That thougts that seems to be present ones, are not because they can only come from memory (because we learnt them in a way or another), so they are thougts from the past. The self-consciouness is the knowledge of our past. One question is then what does the cat know of his past ? Nothing because it has no thought, of course it has a past, but it cannot know it because it can’t talk about it. That means that human’s consciouness and not consciouness (the one we have in common with the cat) is related to the language’s part of the brain. Another question is what is the point to remember the past ? Of course, it’s the only way we have to predict things (see Aristotle). Then what does this means ? Me and the cat we can take a plane to go somewhere, but only me will know where I’m going and that I will be able to get out of the plane when we’ll arrive. When I am in the plane, I should have thougths that tells me I will be able to get out of that thing we called a plane, otherwise like the cat I will be afraid when the doors close or I won’t get in. My thougthts can’t be dissociated from my actions, that I get in the plane, and that I will get out. They are the “context” of what I’m doing. Human’s consciousness is the only way to chain one action to another one, when one (I get in a plane) anticipates another one (I get out of the plane). But men only do that: to anticipate… So consciouness is only about what we would have done (so we can learn) and about what we will do. It’s only the context of what we are doing.

So the problem with your post is the following : you won’t solve this mystery trying to relate consciousness to perception, because it’s always related to a previous one. When I get in the plane, I don’t tell to myself it’s OK I will be able to get out, because I know it (like a cat know something). It’s when I’m in the plane, that I don’t have to forget to get out. Consciousness doesn’t decide anything, because the decision is in the action itself, it’s when I got in the plane, that the decision to get out was taken.

Maybe I’m too succinct, but it’s difficult to use a foreign language :-).

Hi hervé, thanks for your comment.

In conversations about our theory, I try to avoid using the word ‘consciousness’ anymore than I have to, because it’s very squishy and confusing. So I’m not sure that you and I are specifically talking about the same thing.

I definitely do think that cats and other mammals have their own version of subjective experience. This is because they also have hippocampi, and they use them for very similar purposes (way-finding, offline learning, reliving previous experiences, integrating neural information, and even future projection).

I think that any animal that has episodic memory must also have some sort of experienced self, because the ‘self’ in experience is just a strategy of episodic memory. If memory was only of events, but included no ‘I’, then the recall of that memory would not have enough context. I would not be able to remember who did what, or how I felt about the event.

I think most mammals also have future projection; i.e. mental planning. This allows them to figure out a route through a tricky environment by sight alone, without having to bump into everything along the way. A rat uses a combination of episodic memory to remember where the reward used to be in the maze, and future projection to drive his movement toward the site of that reward. As with episodic memory, the hippocampal self is needed for future projection, at least to represent the dimensions of the animal’s body, before it tries to squeeze through obstacles.

The big difference between animals’ and our use of the hippocampus memories and future planning is language. Immediately after an event, we can replay it in our minds, and have a very vivid sense of re-living that event. But very soon, we start consolidating parts of that memory with language. Language can serve as a mnemonic, like “I was driving to work”. These five words relieve the episodic memory system of having to replay all the actual driving. So human language tends to condense memories quickly down to their gist.

This is also true of future planning. If I’m getting on the plane, even if I have no previous experience with flying, I can be told that the plane is going somewhere, and that I can get off that plan, upon arrival. The cat cannot be told that. But neither can a human infant.

What distinguishes us from other mammals is not that we have this unique thing called ‘consciousness’ which allows us to understand concepts. What distinguishes us is that we have this unique thing called ‘language’ which allows us to encode, and then subsequently decode and share, concepts.

I hope this helps.

Yes, it helps a lot :-). I will read your publication.

I think that what you call “future projection” for mammals is confusing. For them, it is only “what to do next”. It’s easier to find the way in the maze like that. I need food, what to do next. I have gone here (I’m here), what to do next. His memory gives the rat the answer at each step because it knows the way. The rat doesn’t “plan” to find his way through the maze. Am I wrong ?

I think you are right about language (and the rest also :-)). I think that human’s consciousness is the memory of what we can say, when the rat’s “consciousness” is memory of what to do next (and maybe human can do it too with a lot of practice). When you say “so human language tends to condense memories quickly down to their gist”, it is more than that, because it allows us to reuse it in another context. I can get in a Boeing or get in an Airbus, for me it is the same. If the plane is the rat’s maze, it will have to learn it again (even if it is easier because the planes are so similar). But the language doesn’t allow us to “encode” and “decode”. A sentence is like a “symbol”, we think we can encode and decode because it is easy to create a new one. That means we have to learn sentences, not the words, the verbs and the way to arrange them. Anyway you are right the difference between us and the other mammals is the language. But that means something very important, with it we can relate one memory to another. When I see me in a miror, I can make a relation with the previous time I have done it, and then conclude “it’s me”. The key is that in this way we can know the past and compare it to another past. I think that’s the difference between NSE and what we call consciousness, even if you are right that this word is confusing. I think that it changes nothing to your model, but your model seems good for “what to do next”, and maybe I should try to translate “I will go to Edinburgh” in “what to do next”. But then, I will have a problem, I have a lot of “what to do next” at the same time when the rat seems to have only one. To tell it another way, the “hostess asking me what I want to drink” is it the “input (senses)” that remembers me that “I have not done that or that before leaving home” ?

I’m not sure what I’m saying can be useful for you.

Anyway, I was very pleased to read you.

Hi hervé, thanks again.

I want to briefly disentangle the major networks of the brain, the nodes of each which often interact and collaborate on tasks. There is a large community of networks that I think can rightly be called the ‘extrinsic’ network, because it is focused on tasks that exist outside of the mind, like the outside world and my body’s immediate (<2sec) response to it. This network includes all the sensation networks for input and the motor and speech networks for output. Then there is the default network, at the midline of the cerebrum, which acts as the 'intrinsic' network, meaning that it is concerned with tasks of the imagination, like future planning, mental previsualization of spatial tasks, theory of mind and initiating memory recall. Both networks interact with the amygdala and nucleus accumbens, which provide punishment and reward encoding, respectively. And all three networks interact with the hippocampal formation, utilizing its experience-generating powers to create mental simulations and episodic memory, using its recurrent circuits to buffer information, using its integrative power to help match stimulus to emotional response, using its place cells to way-find, using its time cells and theta organiztion to keep track of sequence, and using its recall powers to conduct offline learning. All these processes involve coordination between the various major networks.

And in each case, the hippocampus creates an experience, whether of driving down the street, or being a body in a sport, or imaging a scene as you read a book, or having a conversation in which you simultaneously conduct theory-of-mind simulations about the person you're talking to, or of watching a movie in which someone else's reality predominates, or of meditating. All these different ways of having experiences still involve the hippocampus stitching together upstream information from the various networks, and generating an episodic memory engram, i.e. a piece of neural information that is encoded within a theta wave. It is when that engram activates various sites around the brain, in all the major networks, that we have experience, according to our theory.

So no, 'consciousness' doesn't do anything. It is rather the simulated experience of: being an 'I' who is doing things.

We humans have perceived I's with very active minds, often with lots of inner language. But our brains don't need language to think. Thinking happens at the synaptic level. Language is just added to the process of thinking so that it can be encoded into an episodic memory and be recalled later. The hippocampus is the brain's best way of holding on to long-term information, so anything the brain wants to make sure it holds on to, it offers as language thought to the hippocampus, getting it to encode that thought for possible future use. This includes a lot of narration about events in our lives, as we live them, and/or as we look back on them. That narration provides mnemonic to the memories, encoding our best guess at what happened in an event, and the lessons we should be learning from it.

Because we are so used to hearing our own language streams within our subjective experience, we end up with this certainty we have that: 'I am thinking'. And thus we believe that the experienced 'I' really is the thinker. But the real thinking all happens out of view, prior to the buffer, in what we call the unconscious. Our experience of mind is just part of the hippocampal news report.

Again, this is why I shy away from the word 'consciousness'. Because subjective experience unites representations from all the different networks and functions, therefore the word 'consciousness' has come to mean all those various networks' functions.

But there is no such network in the brain which does all that. There is just the brain, doing its thing, and then there is a news report about the brain's processes, which provides memory, and which gives rise to experience. It is this experience which has created the illusion that the perceived world is the actual world, and that the perceived self is the actual me. 'Consciousness' (as meaning anything more than neurotypical subjective experience) is just an illusion.

Thank you for this answer. I prefer to think about it and read your full text because I’m afraid to bother you since I don’t know much about brain from the inside.

But one thing : “the perceived world IS the actual world” because there is not another one, otherwise everything we say (including this very interesting post) would be an illusion and they will be no world at all. When we say “things are not what we perceived” it only means that we can learn more about them, changing by that the perceived world which is the only one we can know.

Thank you very much.

Maybe I will contact you later (if you don’t mind).

Hi hervé,

I don’t mean to imply that there is NO actual world. Certainly, there is something out there.

But my perception of the world is my own creation. My eyes receive photons from the environment. These photons contain information about the last molecule they bumped into in the form of intensity and wavelength. My retinal cones and rods activate to varying degrees based upon the intensity and wavelength. The retina sends neuronal signals in the form of ‘spike trains’ a precisely-timed sequence of synaptic activations and pauses. These signals get sent through the thalamus to V1, the first and most granular processor in the visual system. From there, vision takes multiple pathways: one interpreting the spatial location of all objects in reference to my eyes, another figuring out the identity of objects. In the latter pathway, coarse processing leads to more refined conclusions, as dots become blobs become edges become shapes. Finally, that object identifying processing hierarchy arrives at the inferotemporal lobe or the fusiform face gyrus, at which point objects and faces are recognized. Recognition involves the visual cortex signaling the perirhinal area, which is a concept-associating structure in the hippocampal formation. The ‘concept cells’ in the perirhinal area associate all the widely distributed semantic information about an object, like the sight, smell, taste, and texture of an orange. The actual functions are in their respective cortices, but the concept cells unite them through common activation.

Finally, the conceptual information from the perirhinal area is fed into the entorhinal cortex, the hub in and out of the hippocampus. There, it joins sensory feeds from earlier in each hierarchy, so that objects and faces in memory/perception have both sensory and conceptual qualities. The entorhinal cortex organizes all this incoming information from all around the brain (the news reports) and feeds it into the hippocampus for binding into an episodic memory engram. In our theory, it it is the engram which completes the loop, feeding out on bidirectional pathways to re-activate the very cortices which contributed to the build-up of the current moment engram. This re-activation we hypothesize to be equivalent to neurotypical subjective experience.

That end product, NSE, is what we call perception. It is very much a construct of our brain. It is the only world we remember.

Sure, there is a real world out there, but our experience is shaped at every level by our neural architecture and our previous conditioning. Our perceived world is an interpretation of the actual world, but it is absolutely not the actual world.

Matt Faw says: “We humans have perceived I’s with very active minds, often with lots of inner language. But our brains don’t need language to think. Thinking happens at the synaptic level. Language is just added to the process of thinking so that it can be encoded into an episodic memory and be recalled later.”

Matt, have you addressed the issue of over-determination?

“Overdetermination occurs when a single-observed effect is determined by multiple causes, any one of which alone would be sufficient to account for (“determine”) the effect. That is, there are more causes present than are necessary to cause the effect. (Wikipedia)”

For example, above you say that “language” is added to the process of thinking so it can be encoded into episodic memory and be recalled later.

But isn’t language really just synaptic firing? Isn’t subjective experience really just synaptic firing?

If the answer is “yes, it’s just synaptic firing,” then why does SE exist?

If the answer is “no, it’s not synaptic firing,” then what is SE?

Matt Faw says: “Our perceived world is an interpretation of the actual world, but it is absolutely not the actual world.”

Of course, this would include brains, neurons, and synaptic firing. I think here you will find the answer to the above question.

Hi Dustin, thanks for your comments.

Language is not synaptic firing. It is a culturally agreed-upon code that allows our species to share information at an unprecedented richness. Since language is so adaptive, our brains have evolved to be very efficient and effective with language.

Language thought, like all thought, is due to synaptic firing. However, it serves a specific function, that not all synaptic firing will serve. Image thought allows us to pre-plan physical actions, like figuring out our next chess move or how to pack boxes in a car trunk. Image thought is the simulation and manipulation of visual symbols, in order to figure things out without too much trial and error. Language thought is similar, in many ways, a manipulation of symbols, for the sake of problem-solving. It allows us to imagine how a conversation would go with someone else. It allows us to buffer information in our heads, for deliberation. It also allows us to encode conceptual information into episodic memories, by creating narratives and rationales about why things happened the way they did.

Subjective Experience is another form of symbol, a complex symbol that can include not only perceptions of the outside world and feedback from the body, but also language and image thought. The default network uses the hippocampus as its ‘holodeck’, its mind’s eye. Among other simulations, the default network and hippocampus generate mental imagery, theory of mind, daydreams and more. I believe that language thought is also generated by the default network, utilizing the language cortices of the neocortex, and buffering within the hippocampus, also for problem-solving.

Subjective experience includes all information that is processed in the hippocampus, both the ‘mind’ aspects of the default network and the body+world aspects of the neocortex, insula and amygdala. SE is encoded within the hippocampal theta wave output, as part of a complex temporal code.

SE is caused by a whole pyramid of brain processing, information from all around the brain. Yes, each bit of information is communicated by synaptic firing, but SE is a global activation caused by a complex informational structure.

Our perception of the world DOES NOT include brains, neurons, and synaptic firing (unless one is a neurosurgeon). All that stuff is under the hood, out of sight. Those things are the causes of perception, but they are not themselves perceived.

The actual world contains brains and so on, but it does not need perception to exist. Nor can we perceive the actual world as it actually is, because we are constrained by the mechanisms that evolution built in us. Dichromats perceive fewer colors than color-normals, but that doesn’t mean that color-normals see the “true colors”. We just see the colors that our eyes have evolved to detect.

I’m not sure why you are trying to reduce extremely complex phenomena to “just synaptic firing”. That’s like saying that love is “just brain chemicals”. It’s technically true, but I don’t understand why the word “just” is warranted or useful in either case.

Why do we have SE? We should first ask why do we have episodic memory, because SE is just a side-effect of the episodic memory system. We have episodic memory in order to have offline learning (i.e. learning after the fact). It also allows our brain to rehearse new skills and concepts, while asleep. And, of course, it allows us to make sense of the past, and plan for the future.

SE is needed for episodic memories to make sense. When the memory is recalled, the re-activated regions of the brain need to have some familiarity with the original episode, or they would seem like fantasies. So the hippocampus activates sites all around the brain, as a way of priming them, both for the next moment’s processing, and for future recall.

I hope this helps.

Matt Faw says: “I’m not sure why you are trying to reduce extremely complex phenomena to “just synaptic firing”. That’s like saying that love is “just brain chemicals”. It’s technically true, but I don’t understand why the word “just” is warranted or useful in either case.”

Because I’m pressing the issue. I think this is a wonderful theory, but it doesn’t explain why we have SEs such as green, sweet, salty, love, etc.

Rather than there existing such SEs, why isn’t there just “hippocampal theta wave output, as part of a complex temporal code?”

Unless you can identify a causal role for SE, you will have to deal with over-determination. In other words, you haven’t explained why SE exists, you’ve just identified its physical correlates.

To flip back and forth between SE and causal, physiological processes is problematic.

Hi Dustin,

Here’s a practical example of why we need qualia: say an organism is out looking for food, and comes across a brand new berry, on an unfamiliar bush. The organism is hungry enough to try the new berry, but its novelty detector is activated, causing it to encode greater details about the plant in its episodic memory system.

In this example, let’s say the organism goes several hours before starting to feel symptoms from the new plant’s toxin, not enough to kill it, just to make it sick. This is not an immediate pairing between stimulus and response, but a very delayed one, which the neocortex is poor at associating.

The hippocampal system is needed to encode details of the new berry/bush, so that, should symptoms later appear, they can be associated with the color of the new berry, the shape of the leaves, etc. This is offline learning, and it only happens if there is an episodic memory system.

The organism, once it feels the symptoms, uses recall to re-experience the color and shape of the offending berry, and then connects the one memory (qualia of the berry) with the other (qualia of the toxin). This process requires both qualia of the outside world, and qualia of the body.

Later, when the same organism stumbles across a similar berry, the color and shape will elicit the memory association, and the organism will hopefully avoid the berry a second time.

This is why qualia is a necessary part of the episodic memory system.

Subjective experience happens (in our theory) when the episodic memory system elicits a global brain activation by the brand new memory, the one that reflects what just happened ~300ms ago. Qualia occurs in SE because the hippocampal output is really a complex cluster of brain addresses, like hyperlinks, which instruct the entorhinal cortex which pathways to activate. This activates far-flung cortices to participate in the immediate global experiencing. Qualia of the immediate event arise from the sensory cortices activating (due to the hippocampal output) to represent the shape and color of the berry. That immediate activation is part of what is needed in order for the later recall activation to be familiar.

Since the hippocampus also generates virtual experiences for the default mode network, like imagination and future planning, it is important that the qualia of actual experiences feel differently than the qualia of fantasies, so memory does not confuse the two. Therefore, the SE of the current moment event requires vivid qualia, in order for the later recall of that event to be relevant and recognizable.

Does this help?

Edit to add that of course, smell and taste of the new berry are also very important bits of qualia.

Matt Faw says: “Here’s a practical example of why we need qualia: say an organism is out looking for food, and comes across a brand new berry, on an unfamiliar bush. The organism is hungry enough to try the new berry, but its novelty detector is activated, causing it to encode greater details about the plant in its episodic memory system. …

Subjective experience happens (in our theory) when the episodic memory system elicits a global brain activation by the brand new memory, the one that reflects what just happened ~300ms ago.”

I appreciate you taking the time to answer my questions. However, again, what you’ve done is explain how and why SE is correlated with physical processes. Why does global brain activation have to feel like something? Why can’t it just be… global brain activation. That is, you haven’t established a causal role for SE. You’ve just essentially said it accompanies global brain activation.

Thus, you unfortunately haven’t explained (1) why SE exists in the first place, and (2) how it might arise mechanistically from physical processes.

As I’ve noted, I think HST provides a wonderful description of how specific brain regions and processes are coupled to specific SEs. Descriptions that I haven’t found in any other model. But imo questions (1) and (2) remain unanswered in this model and thus the ultimate questions regarding SE remain unanswered.

Hi Dustin,

I’m not entirely sure how to respond to your comment, because in my last response, I think I did answer, quite precisely, why we have Subjective Experience.

If your question is “does global brain activation have to feel like something”, I think the answer is no. There does not need to be experience, in order for there to be response. That’s probably true for plants, although I can’t say for sure.

However, if the question was: is feeling useful? then the answer is obviously yes. Distinguishing between colors of berries to figure out which is poisonous is extremely useful. Being able to distinguish your friend from foe, being able to feel when you are in pain, being able to respond to hunger or cold or fear, these are all very useful functions.

If the question is: is episodic memory useful? then the answer is obviously yes. It’s very hard to learn, without a sense of history.

If the question is: does having feeling being part of episodic memory useful? then the answer is obviously yes. Episodic memory would be barely useful (especially to animals without language) if feeling were not involved. We could not learn, and we would be extremely inflexible, if we only worked upon pre-programming. We would only respond to our immediate environment like a sponge, just soaking up nutrients, if we could not remember our past and learn from it. Any animal that needs to find food and water needs some form of memory, and without language, feeling is just about the only memory we can have (some concepts exist, pre-memory, but they are very rough).

Evolution is not about what has to be. It is only about what is useful. So the ‘why’ of almost any biological process is not a philosophical question, but a biological one, a historical one.

Now for your other question, how does it arise mechanistically from physical processes? Certainly there are some mysteries still that need to be answered. But is that really any more mysterious than being able to use language? Or monarch butterflies navigating back to breeding grounds that their grandparents lived at, but not them? Or a host of other amazing biological processes? These are all mysteries that science is still trying to answer, and even when it does, it still explains ‘how’ it happens, but rarely ‘why’ it happens (other than usefulness). I don’t see why experience is any more mysterious or confusing than any of these other unexplained details of nature.

I’m happy to answer more questions about the theory, if you have them.

Edit to add: evolution is about some necessity. We must have replication and mutation, in order for there to be evolution. But the rest is just about usefulness.

Matt Faw says: “However, if the question was: is feeling useful? then the answer is obviously yes. Distinguishing between colors of berries to figure out which is poisonous is extremely useful. …

Now for your other question, how does it arise mechanistically from physical processes? Certainly there are some mysteries still that need to be answered. But is that really any more mysterious than being able to use language? Or monarch butterflies navigating back to breeding grounds that their grandparents lived at, but not them?”

Distinguishing between physical, objective EM waves reflected by various objects is not the same as distinguishing between subjective, qualitative colors such as blue, red, and green.

You simply can’t flip back and forth between objective and subjective properties. So, no, you haven’t provided a empirical explanation of why SE is useful. Sure, you’ve provided a theory/model as to why various SE and physical processes are correlated (objective EM wavelengths and subjective phenomenal color) but you haven’t explained why SE exists in the first place.

For example, brains could simply encode various EM wavelengths an report them as global synaptic firings. And that could be the end of it. There is no reason (that you’ve provided) to invoke SE.

Re: the mystery of SE

Absolutely the existence of SE is more mysterious then the examples you give. There are currently zero physical/biological models that get anywhere near providing a valid, empirical, mechanistic explanation of how non-feeling, physical processes could give rise to feeling.

“It must be confessed, moreover, that perception, and that which depends on it, are inexplicable by mechanical causes, that is, by figures and motions, And, supposing that there were a mechanism so constructed as to think, feel and have perception, we might enter it as into a mill. And this granted, we should only find on visiting it, pieces which push one against another, but never anything by which to explain a perception. This must be sought, therefore, in the simple substance, and not in the composite or in the machine.” ~ Leibniz

Hi Dustin,

You present a series of epistemological and metaphysical assertions, most of which I disagree about.

You say: “you can’t simply flip back and forth between objective and subjective properties.” But why do you assert that? How else would one explain subjective properties in an anatomical system, other than connecting their properties within the same sentence?

You say: “brains could simply encode various EM wavelengths an report them as global synaptic firings. And that could be the end of it.” But is that really true? Could that organism really exist the way we do? How does that organism fare, when it comes to the poison berry problem I posited above? How does it learn, if it is not able to re-call, not just the electromagnetic wavelengths, but the actual feelings involved with first experiencing the berries and later experiencing the toxin? We call those feelings “red” and “nausea”, but the names are unimportant to most organisms. Feelings must exist, in order for organisms to learn and adapt.

Look at the difficulty that robotics designers have had with machine vision and navigation, and they were able to design their systems from scratch. It is not such an easy thing to exist without perception.

Even if, in all the world, such an organism exists, it does not change how we mammals with hippocampi function. Just because an alternate system might possibly exist, I don’t understand how that invalidates anything that I’ve written about our own brains. I hear you claiming a problem, where no problem exists.

Of course perception was mysterious to Leibniz. Most brain processes are still mysterious to us now, in the 21st century, and brain science has come a very long way since Leibniz. But is it really the most mysterious thing?

I listen to improv comedy, and admire the performers’ ability to listen to each other weaving fantasies and joining in with lines that are not only made up on the spot, but are really funny. That, to me, is a truly amazing feat. Watch a nature documentary, and they’re full of incredible things animals do, that boggle comprehension. I don’t buy that those are any less amazing than perception, no matter how many philosophers you quote. Perception, it seems to me, is just a biological process, like digestion, and falls squarely within the same category. You can claim its mystery all day, but I don’t see any reason to agree.

I would be happy to answer questions about the theory, but I hear you just moving the goal posts, and declaring mysteries for the sake of them being mysteries.

I’m sorry but you cannot say that “feelings must exist, in order for organisms to learn and adapt”. The feeling and the things we can feel exist at the same time. If there were only poisonous berries, your organism would die with its specie. The feeling and the organism has evolved at the same time, so only the one that feels the right things exists. Thus the feeling exists so we can adapt to the things that exist at the same time. It doesn’t seem so with humans being because all the things we adapt to are humains things since we can talk about them, and each of us have learned to adapt to them (but it is the same, the one that cannot adapt to supermarket, money and credit card will have difficulties). But, that’s the reason why NSE should be a bit more complex for us than for the other mamals.

Hi hervé,

I’m sorry; I don’t quite follow your point.

Let me try to phrase my argument a little differently, and see if it covers your concern.

We feel hunger. But one could argue that we don’t need to feel hunger, because we could instead just have a switch which activates, telling us to go get food, which we act upon. Why bring feelings into it?

Indeed, we do have internal switches, which drive us toward food, even absent the feeling of hunger. That’s part of why we have our obesity epidemic, is because people eat according to various cues, in addition to hunger. But the feeling of hunger is an alarm, which kicks in if our prior switches have not yet activated our food-gathering behavior.

The feeling of hunger, however, is a more subtle and flexible factor than a simple switch. If an organism is hungry, but the only nearby food source is extremely dangerous (say, a porcupine or a poison berry), then the feeling of hunger must be weighed against the feeling of fear. We can see in the warming arctic that polar bears are starting to swim farther and farther from the ice floes in pursuit of food, because their hunger is out-weighing their fear of drowning. But that’s a new event, due to extreme circumstances; the fear of drowning will usually keep polar bears from swimming too far from land / ice floes.

Feelings allow for conditional responses, context-informed responses, not just mechanistic stereotyped responses. They allow us to analyze the entire situation, not just the individual stimuli within it. They allow us to remember previous experiences, because feeling (by which I mean all sensation, emotion, etc.) is what is remembered when non-language organisms recall episodic memory.

We use credit cards and supermarkets because we have a shared conceptual culture of transaction with those items. But the non-language animal which has eaten the novel berry needs the sensations associated with that berry, in order to associate them with the sensations associated with its later stomach ache. It is not born with the concept of which berries are poisonous; most likely, it is born with the concept that some foods are safe and some not safe. It takes unpleasant trial and error to figure out which ones to avoid. Only through memory can that trial and error lead to learning, and only through sensation/feeling can that memory be useful.

Does this help?

Matt Faw,

Thanks for your time!

The Hard Problem of consciousness and the Mind Body Problem are not moving the goal posts. Those posts have been there for thousands of years.

For your theory of SE to be taken seriously, you will need to address those problems or explain from the outset that your theory does not answer them.

If you do not understand why switching back and forth from 3rd person explanations and 1st person explanations is problematic, then I suggest you ask some trusted colleagues to explain.

Cheers!

Dustin,

Of course I understand Chalmers’ and others’ versions of the hard problem, and I think I’ve given them full justice above.

The various ways of asking the hard problem, according to Wikipedia:

From Chalmers: “Why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life at all?” I have already explained why episodic memory is useful, and why feeling in episodic memory is necessary. And, according to our theory, episodic memory is exactly equal to our rich inner life.

Other variations on the same problem:

“How is it that some organisms are subjects of experience?”

Answer: because if we did not have our virtual selves as the subject of our memories, then our memories would not have sufficient context to be useful. If I remember an event, but don’t remember what I did in that event, nor how I felt about it, then that memory is not helpful for learning.

“Why does awareness of sensory information exist at all?”

Answer: because if we did not have memory of that sensory information, we could not recall it later, and we cold not have offline learning. What we know as ‘awareness’ is really the unified memory of nodal awareness, which we subjectively do not have access to.

“Why do qualia exist?”

I’ve already addressed this, at length.

“Why is there a subjective component to experience?”

Like above, if we didn’t have the subjective component to memory, the memory would be near meaningless.

“Why aren’t we philosophical zombies?”

Answer: because philosophical zombies could not learn through association of events that are far-flung in time. They would suffer from the poison berry problem. Only by experiencing events and then safely re-experiencing them, can our brains learn efficiently from them.

In other words, all these “why” questions are answered by the usefulness of episodic memory. And why they are part of SE is because SE is caused by a brand new episodic memory, full of vivid detail.

As far as I can tell, I have fully addressed the hard problem. If you have further problems that you think need to be resolved, then please explain your questions more thoroughly, rather than tell me that I should “ask some trusted colleagues to explain.” I can only do my best to answer questions as they come at me (and I think I’ve made a pretty sincere attempt to do so, above), but if you just claim I haven’t solved a problem without being willing to fully define the problem you’re talking about, then you’re not attempting to have an honest conversation with me.

I don’t get the “movie” part (who is watching?) isn’t there just a new signal assembled and sent?

Hi dmf, thanks for your question.

True, no one is watching the movie. That’s where the metaphor gets tricky. The hippocampus is not a theater, in which an observer sits and takes in the movie of subjective experience.

The hippocampus is rather like a news media outlet of the brain. The entire brain processes and responds to the needs of the current moment, and then the ‘newsworthy’ (i.e. dynamic, novel, or changing) results of the brain’s processes are sent to the hippocampus for memory encoding. The hippocampus binds all these news reports into one unified report of reports, the episodic memory engram. That engram is ‘broadcast’ from the hippocampus on a theta wave output, activating sites around the brain. It is that global activation by the unified engram which is equivalent to subjective experience. So, no individual brain area is the observer, but (essentially) the entire brain is activated into having an experience.

By analogy, the visual cortices do not ‘watch’ the outside world, via the eyes. Rather, they are activated by the outside world (via the eyes), and that activation gives rise to representations (i.e. constellations of activations which connect sensory and conceptual data). These representations from the visual cortices and others are what is bound within the hippocampus into the master representation, the new memory, and that new memory re-activates the visual centers, among others, creating experience.

Another important metaphor to help understand the function of the episodic memory engram is the ‘player piano roll’. In a self-playing piano, the metal cylinder that plays within it does not have a song encoded on it. Rather the player piano roll has a bunch of bumps and notches, which tell the piano how to re-play the original tune. It is the job of the entire piano to re-create the song. Likewise, the episodic memory engram is just a collection of pointers to various cortices which contributed to the formation of the memory. They are like hyperlinks, ready to re-activate their source site.

The episodic memory engram, formed in field CA1 of the hippocampus, is read by the entorhinal cortex (EC), the hub in and out of the hippocampus. The EC activates bidirectional pathways, re-activating sensory cortices and others, giving rise to the global experiencing. The theta wave that contains the new memory is the timing signal that allows all cortices, no matter how far from the hippocampus, to agree on the ‘now’ of the experience.

That picture is complicated somewhat, because there are some sites around the brain which receive the entire hippocampal output, i.e. ‘the big picture’. This includes the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, which uses that output as a complex conditioning input. That means that rather than just being conditioned by individual stimuli from the outside world, we also have conditioning by gestalt situations. And we also respond to gestalt situations. So the vmpfc receives the hippocampal output and algorithmically uses the whole event to activate emotional response and appropriate response.

The orbital frontal cortex receives the whole hippocampal output, and seems to be engaged in error-checking for it, making sure reality stays consistent. And the temporal-parietal junction receives the whole episodic memory engram, and uses it to compare that representation of body-in-space, with the various representations of body-in-space created by the posterior parietal visual center, the somatosensory center, the cerebellum and the right hemisphere temporal lobe. The TPJ is an error-correction center for body-in-space representations, which is why damage to it can cause body-in-space distortions.

So it’s a somewhat complex situation: some cortices receiving the entire engram, some just activated via the EC, but the overall global effect of the activation is what we know as subjective experience.

I hope this helps.

yes thanks I’m familiar with the physiology which is why I was puzzled by the choice of metaphor, better I think to stick to the signaling and avoid misleading appeals to folk-psychologies, and along those lines we should likewise be careful in the use of terms like representations.

Matt,

The thing is, I think your theory (and others like it) can provide an answer to the Hard Problem and to the Mind Body Problem.

When I said that SE was really just synaptic firing and you said, yes, that’s technically true, you shouldn’t have. You should trust what your own Theory and research are telling you.

You’re suggesting that our perceptual system is a virtual reality machine. When we look at reality, this system provides us with a virtual reality that allows us to adaptively interact with reality.

But what happens when this perceptual systems looks at itself? Yes, it sees brains, neurons, and synaptic firings.

But don’t forget that even this is a virtual reality!

Now, we know that there really is a reality out there. We know there really is a perceptual system generating our virtual perception of real reality.

But don’t reify the virtual reality!

I’m not saying that brains, neurons, and synaptic firing doesn’t really exist in reality.

But at the same time, we mustn’t lose sight of the fact that what we see is a virtual simulation of reality, not reality in itself.

Leibniz says we mustn’t look for the form or composite to find “feeling” but look to the substance.

Well, our perceptual system can only create a virtual simulation of the form and substance of reality.

So when we perceive matter, we must understand that we are perceiving a simulation of reality.

We are perceiving a simulation of the ultimate substrate of reality.

Now, we know that phenomenal consciousness exists, but we can’t see how it arises from matter.

But we realize that matter is a perceptual simulation of the ultimate substrate of reality.

Therefore, trying to get consciousness from matter is a red herring because matter is only a perceptual simulation of the true substrate of reality.

My theory is very much about our virtual realities, so there’s no denying it. We absolutely each live in our own reality bubble.

I’m not reifying the virtual realities; they exist only in our individual brains as a chain of memories, and are absolutely not equivalent to ‘actual reality’. Of course, actual reality is only subjectively known by individuals, but that’s what science is for, testing reality from many different angles, in order to remove individual bias. Our theory is still in the hypothesis stage, and so reflects my bias, but it is very much built upon a huge trove of peer-reviewed science.

I am explaining the anatomical basis for subjective experience. This is not a ghost in a machine; this is information processing. There is no self-like consciousness that receives perception and guides the unconscious body; that is an illusion, created by the fact that SE has a self-model within it. There is only body, part of which is the brain, and the brain tells itself a movie-like story of self-in-the-world, for the sake of future recall. We have historically mistaken that story of ongoing memory for the actual reality, but since Kant of course we know it cannot be.

Can I challenge you to please read the actual paper? I worked for three years on it, and the explanations are more thorough and the word choice within it is much more precise than I can possibly be in this comment section. It doesn’t spend much time on the hard problem, but it is very clear about explaining the ramifications of the theory.

Matt,

I have read the paper! It’s excellent. I love the theory. As I’ve noted, it explains aspects of SE that other models/theories do not.

But when you offer a theory of SE, people are going want it to address the Mind Body problem, how does matter and mind (feeling/phenomenality) relate? In our time, where physicalism is king, we ask how does feeling/phenomenality emerge from matter?

Your model presents a wonderful explanation of why pheno0menality/feeling is structure for us in the way that it is (i.e., it’s a *virtual* reality allowing us to adaptively interact with reality).

But like all simulations, it doesn’t fully capture the process it is simulating.

In this case, the processes that human perception fails to capture is phenomenality itself. Thus, when we perceive the world, it appears to consist entirely of non-feeling matter. To the point where some even deny that non-human animals are conscious.

We simply cannot see/perceive/simulate phenomenality.

But we know feeling/phenomenality exists, because that’s the substrate from which our SE simulations are made.

Hi Dustin,

Thank you for reading the paper and for your kind words about it.

Certainly, our paper is not intended to be the end-all be-all of every philosopher’s every question; I’m not sure what that would take. And there are certainly neural questions that I don’t try to answer within it, like what neurons precisely are activated by the hippocampal output or how precisely a cluster of neurons activating is equivalent to the perception of red. But I think we can get there from where we are.

What I do think we’ve been able to solve is the binding problem (information from all the brain gets bound together in the hippocampus for the sake of generating a global experience). We’ve explained why so much of brain and body information is left out of experience (it is not ‘newsworthy’, i.e. dynamic novel or changing enough to be useful to memory). We’ve at least outlined what the subjective appearance of self probably is, and why it is clearly a confabulation. And we’ve established the relationship between perception and the ‘unconscious’.

And because we’ve created a theory based upon information, being shared between brain nodes, we avoid the panpsychism-like problems. We are not talking about an essence called perception, which arises from inanimate matter. We are talking about information being shared between processing centers, causing activations.

This is not unlike the pixels on a computer monitor being activated by the information from its processors. There is no ‘hard problem’ of your graphical user interface arising from the matter of your monitor, and subjective experience is really the same kind of thing. It is a user interface. It is an activation, based upon information processing. In our heads, the activation includes not just pixels of color and shade, but also concepts, aesthetics, emotions, moods, etc., but they are just different flavors of the multidimensional display of our brains. It’s all still activations by information.

So yes, there are still details to be worked out, but I don’t think there are really large gaps left.

Thanks again for taking the time to read it, and for your kind words.

Dustin, I understand from your comments that you think that Matt’s HCS theory makes sense physically, but you object that the theory fails to explain the hard problem any better than any other theory.

I think you mean that we run into the problem of what seems to be a qualitative experience for which no satisfactory material explanation has been found. Why should we have these qualitative, subjective experiences simply because some kind of electro-chemical network comes into existence? Why don’t other parts of our brain’s networks also “feel” qualitative experience? Why don’t computers experience qualia? Why does a Hippocampal Simulation have qualia?

I don’t have an answer to that, but in my view this still seems to tackle the problem from a dualist perspective because we are assuming that these qualia have some material existence. As you say, “So when we perceive matter, we must understand that we are perceiving a simulation of reality”. Here you seem to have invoked some kind of inner viewer, the viewer who perceives a simulation of reality.

Perhaps in fact what we perceive, whilst it can be abstracted into a “simulation of reality”, is nonetheless not that at all. Surely perception can not be any more than how cells in our brain respond to inputs. Physically, all we have are cellular behaviours. No qualia whatsoever. Red is not some qualitative property of light, it is merely how certain cells responded to incoming radiation of particular wavelengths. We aren’t “seeing” red for the simple reason that “we” aren’t seeing anything at all.

A simple question one might ask is, given the considerable brain-power thrown at the problem of qualia, why is it that not the slightest clue to how there might be such a thing has ever been found? And yet as I note, we have considerable success at unravelling physical processes in the brain that apparently correlate well with claims of subjective experience and that predictably match behavioural outcomes. Chalmers’ “easy problems” appear amenable to scientific method and thus far have proven open to explanatory deconstruction.

Given this, wouldn’t it be more rational to conclude that mental states don’t exist as such and simply accept that fully explaining physical operations in the brain is all that is required? Once we have these fully described, there is nothing left over. There are plenty of people doing this and saying this, but dualism and Chalmers’ “hard problem” seem to exert a hold on us that we find so seductive for the simple reason we cannot bring ourselves to believe that there is no “us” in there.

Look at Hameroff and Penrose. It’s telling to me that when asked if he believes in life after death, Hameroff proposes some kind of leaking of quantum information from within microtubules that simply continues to “hang together” due to quantum entanglement. And Penrose only recently went on record arguing for this exact same idea. They seem rather keen to prove that we exist as something separate from our physical bodies. Which is fine, but hardly very objective.

Isn’t the simplest explanation just that a mental state is simply a conceptual device that linguistic consciousness has thrown up to describe what we do? That in fact, all there can be is a physical brain doing lawful physical things and we are simply misled into thinking that there is more to it.

This idea has been around for a long time, but the comforting seduction of believing we exist in some unphysical manner has proven a formidable barrier to its broader acceptance. I suggest that as more research goes on we will get closer and closer to actually specifying the physical nature of human consciousness.

People talk of qualia as some kind of property we can distinguish above and beyond the merely physical. This was the basis for Jackson’s “Mary”. Yet, what ineffable quality makes red, red. Or a pain, a pain. I cannot think of any. If all you had experience of was the colour red and you had no language available to you, what would the experience of red feel like? Or pain? Qualia only gain some sense of ‘feel” in the presence of other qualia and appear to constitute a comparitive function to serve the organism in establishing flexible behaviours.

In behaviour, colour or pain exist only to serve action. We use a variety of inner operations to make distinctions about external and internal states such that we can make behavioural choices. Graziano for example makes this kind of claim in his Attention Schema model. Kevin O’Regan comes at it from a similar angle and his work with change blindness certainly backs him up here. Jaynes’ ideas about human consciousness being rooted in language and metaphor I think have considerable explanatory value in that kind of domain as well. Jesse Prinz’s Attended Intermediate Representations theory is another of this kind in which he claims an absolutely physical basis for consciousness as a menu for action. And here in the HCS theory we have another take on the very same thing – that all we have, and all we can be, is the underlying physical behaviour of our brains.

I believe these people are on the right track. As long as we try to take a concept that represents a physical level of nature but imbue that representation with its own separate character, we can never bridge the explanatory gap. Because its a gap we have created from a fundamental misunderstanding about what we are and what we do.

I tend to think that qualia exist, but only as a conceptual device. Physically, we need only explain the physical operations, for the simple fact that this is sufficient. There is nothing left over, it seems to me. And the HCS seems to me a quite novel explanation for the physical operation of subjective experience. I should be most interested to hear what those expert in the field might think of it (or more exactly, on what basis they might dismiss it).

Graeme M said: “If all you had experience of was the colour red and you had no language available to you, what would the experience of red feel like? Or pain? Qualia only gain some sense of ‘feel” in the presence of other qualia and appear to constitute a comparitive function to serve the organism in establishing flexible behaviours.”

Well put, Graeme. I just want to add a real-world example.

On a sunny day, the dominant light source is the sun, and the average color temperature is about 5,600K. On an overcast day, the light source is the cloudy sky, and the color temperature is about 16,000K, a much bluer light than the sunny day.

Of course, the overcast day looks ‘grayer’ than the sunny one, but to our eyes, a red object still looks red, whether the light that’s hitting it is 5,600K or 16,000K.

Color perception is NOT a strict interpretation of wavelength = qualia. Color perception is, as Graeme points out, about contrast, about comparison. It is about orienting the sensory qualities of objects, within the relative context of their environments, and within the relative context of our previous experience.

Yes it was my point :-).

OK for the description, I cannot argue on that and I am sure it is like that. But when you learn the piano, it is not only the neocortex that say to your body you have to put that pressure on the fingers to modulate that sound. It is also the fingers that have to know it. And it is the same when you speak, you don’t only have to know that answer you want to give, but also to move the tongue and the lips. You cannot dissociate the neocortex from the body. And the NSE is there to tell if what you do is OK with what you perceived and to adjust if needed, so you can know if the sound you got is the one you heard before… No?

What I meant is that the neocortex and the fingers know only the result, how you can play now. How to say that? It takes 10 years to learn piano, after that time, you cannot play as you were playing after only 5 years. We are always learning, either to be better, either to learn something new. That is the reason why when we stop playing, we can forget (when the neurons die).

“So I would say that ‘mind’ is the subjective side-effect of having self-cognition-reports included in the hippocampal process”… And I will say that we have to dissociate the part that concerns the body (playing the piano) from the one that concerns the thoughts we have associated: the thoughts that I know and so I can say with my body (tongue and lips) that I play the piano since 10 years. Because without the thoughts I don’t know that I play the piano, I just can do it. And the “will” is just a word that describe (human) actions, it is not something that exists more than consciousness, but it is another subject.

“As for ‘authentic self’ vs ‘ideal self’, I think it is possible that ‘ideal self’ can be there not only to fool other people, but to fool the very organism that generates it.” I disagree with that. The self is what we know from our thoughts (what we can say) of what we can do (like playing piano with our body: the neocortex and the fingers). And what we can say can be different of what we can do. It is an interpretation that fits with the community (what others want to hear). Do we fool ourselves or others, since it is what we have to say? And you say “but will generate a memory-story of being a righteous person, one who has to put jerks and fools in their place”. You mean that the mind govern the body? That they know how to be a righteous person by the mind (by the thoughts), but they don’t tell the body? That if they wanted, the mind would gouvern their body? Of course it is not that. What people do and what people say, are differents movements of the body even if they are linked in the nocortex (when I do that, I have to say that). When we say someone fools himself, it is our interpretation. When I say it to myself, it is what I have to say depending on the context (what I am doing).

“Those words are no more included in their memory, then my blinks are in mine”. How can you blink or say something if it is not somewhere in the neocortex (for the blink maybe not there but in some neurons anyway…)?

“Our remembered self is as much a construct of self-maintenance as it is a construct of social necessity. Even when we are aware that our social self is curated and shaped toward making a certain impression on others, we may not be aware how much our memory-self is curated and shaped toward making a certain impression on our own brains.” It is a difficult subject. First, our memory self is something we could tell to somebody, so it is always a construct of social neccessity. Second, the brain and body are not separated, so when we have a certain impression on our own brain, it corresponds to a result on our body. Third we can adapt for unknow reason (because we don’t know how we learnt it: cf the piano) to do one thing and to think another one. You can interpret it by saying it is curative… I would say it is adaptation.

“We want to remember ourselves as being right and virtuous, and we can do a lot of tampering of our own memories, in order to make that seem to be true.” I am not sure you can generalize. I don’t care to be right and virtuous because I don’t know which right and which vertu are the good ones :-).

It seems my reply got lost.

I’m OK till the mind.