Let’s take the case of a thinker who feels that she knows a proper name but cannot yet retrieve it. There are three kinds of possible ways for explaining how her evaluation has been conducted: 1) she gets direct access to the content of her state; 2) she gets indirect, inferential access to it, or 3) she has no access to content, but can use subpersonal cues and heuristics to predict epistemic outcome. I will defend this third account, which is compatible, I think, with the prominent role of noetic feelings that all the philosophers of metacognition have emphasized. Let me briefly show how the three accounts differ.

1) A traditional speculation in philosophy is that evaluating one’s own beliefs requires introspecting their contents. Introspection has been taken to consist in a specific experience that is entertained while forming a belief. A hypothetical inner sense is postulated to allow thinkers to both directly access their thought contents and evaluate their epistemic value. In Descartes, innate ideas – “seeds of truth” – are easily and correctly understood because, being simple, they are intuited as clear and distinct. Complex ideas, when composed from simple ones, can generate the experience of gaining certain knowledge thanks to a mechanism called “continued intuition”.

2) It has been objected to this view that introspection can, at best, be claimed to access one’s own sensory states and emotions. The propositional contents of one’s own attitudes, in contrast, are not directly perceivable by an inner eye. On an alternative view, then, one’s own thought contents can only be inferred from sensory states and background beliefs and motivations (Carruthers, 2011). Inferring the contents of one’s attitudes, however, requires conceptual interpretations of what one believes, desires or intends to do, as well as turning mindreading to oneself, in order to know what type of attitude is activated. Hence evaluating whether one knows P, or is uncertain whether P, requires a metarepresentational mechanism embedding a first-order thought (for example: a memory state “glanced at”) into a second order-thought (“I have this memory state”). Judging what kind of thought one has is critical for determining the validity of that thought.

3) Whether or not, however, declarative reflective self-knowledge is based on inference, a question remains unanswered, the very question that the Cartesian doctrine of “intuition” was intended to solve: how do we evaluate our cognitive outputs? This is a separate question, which the experimental study of procedural metacognition helps to address. An initial finding has been that, contrary to early theories of metamemory, human subjects do not know what they know (or don’t know) by directly glimpsing into the content of their memory: one can have a strong feeling of knowing on the basis of correct as well as of incorrect partial information (Koriat, 2007). How is this possible? The ” vehicle theory” claims that, while an agent fails (so far) to retrieve a proper name, the mental activity triggered by searching still carries information about validity of outcome. Several subpersonal heuristics have been proposed in order to specify the predictive mechanism involved. One is the “accessibility heuristic”, another is the “effort heuristic”, a third is the “cue familiarity” heuristic. More recently, neuroscience has “unified the tribes”: Single cell recordings make it clear that the kind of cues that rats use (in a perceptual decision) to evaluate their own uncertainty include latency of onset, intensity (firing rates are higher at chance performance) and the coherence of the neural activity currently triggered by a first-order cognitive task (lasting incoherence predicts failure). These cues, however, are related neither to stimulus information, nor to recent reward history: they are related to second-order features, read in the neurocognitive activity elicited by the first-order task. In other words, mental content does not need to be inspected: the brain predicts outcome from observed dynamics in the vehicle.

Granting that a complete description of the mechanism of predictive processing is now available, at least for specific metacognitive tasks, important philosophical questions can be revisited. Why is metacognition (as well as the kind of virtue epistemology defended by Ernest Sosa) “activity-dependent”? Because the crucial information for evaluating future outcome can only be read in the activity first elicited by the performance to be evaluated. Why is it in general reliable? Because the observed relation between heuristics and outcome is used to recalibrate predictive thresholds for future evaluations (proper calibration is a virtue). Why is an evaluation associated with a feeling, rather than with a declarative metarepresentation? Because a feeling is adapted to gradiency in intensity and valence, and hence, to flexible action guidance, not a proposition or a set of propositions. Why are noetic feelings conscious? Because only conscious feelings can adjudicate at a low cost between conflicting affordances: conscious feelings provide a common currency for the decisional mind (of course, much more remains to be said for a full argument).

The vehicle theory of evaluation, in summary, suggests that content is only indirectly evaluated, through the dynamic features of the cognitive processes underlying it. Does it commit us to any form of skepticism? Not at all. Noetic feelings are a powerful predictive and evaluative tool to reduce uncertainty in daily life (how reliable is this percept?) as well as in scientific reasoning (is this computation correct?). Relying on noetic feelings beyond their predictive capacity, however, is a well-known source of illusion. Leibniz observed, against Descartes, that the experience of certainty is a mark “both obscure and subject to men’s whims”. A dialectic of feelings needs to be constructed, in order to discriminate the specific cognitive tasks and contexts in which illusions prevent accurate predictions.

This video of the Dividnorm workshop on Metacognitive Diversity, held in Paris in May-June 2016, presents talks by Asher Koriat, Chris Frith, and many others, dealing with the mechanisms of metacognition. It’s presently in preparation. All the talks will be online within a few days.

Thank you for this post, Joëlle. As you know, I have a very similar view on metacognition. However, recently I have come to think that probably this view on metacognition is not that far from Carruthers’ ISA theory. The fact that in both the vehicle theory (as you call it here) and the ISA theory the subject doesn’t have direct access to the content and the cognitive attitudes of her mental dispositions is a first common feature. Another similarity is that in both theories the content is somehow “inferred”: according to the ISA theory the content is inferred based on sensory information, and the vehicle theory claims that it is inferred based on sensory cues. It seems that in both theories the inference is different (in one it’s a product of conceptual thought and back ground beliefs), whereas the other is the product of training. But still they don’t look so different after all.

Your defense of the analogy between your own theory of noetic feelings and Peter Carruthers’ ISA theory is intriguing. You’re the best expert of how to see your theory. My own view, however, seems to me strongly incompatible with ISA theory. Let me first mention a few central disanalogies, before addressing your two arguments.

1) ISA theory is intended to account for the informational sources of self-knowledge. ISA claims that, aside from having access to our own sensory and emotional senses, we rely on the same capacities to attribute mental states to ourselves, in metacognition, and to others in mindreading. In contrast, I have defended in my book and elsewhere the view that metacognition and mindreading do not share the same evolutionary pattern. A main argument is that monkeys and rodents predict the correction of their own informational states just as we do, without reading their own minds as we can do.

2) ISA includes as auxiliary hypotheses the notion of a global workspace model, the view that the only central workspace is a general working memory system, and a modular theory of mind. My view does not.

3) Granting that metacognition includes a control dimension, it is uncontroversial that it depends in part on executive capacities – i.e. the abilities involved in selecting a behavior as a function of one’s goal, in inhibiting it, shifting it, and updating it. But it also includes a monitoring dimension, whose function is to predict epistemic outcome. This is denied by Carruthers, who claims in his article with Ritchie (2012) that animal metacognition only has to do with appetitive control. This contrast between our views is crucial, because the distinctive sensitivity of non-mindreaders to the validity of their perception directly conflicts with ISA.

Your two main arguments for the analogy between ISA and Vehicle Theory (VT) is that both reject a direct access view to content and that content needs to be inferred. The first argument is correct, but at the cost of precision. ISA rejects direct access to one’s own mental states, because they should be inferred. VT rejects the relevance of thought contents in evaluation, inferred or not, because only the neural dynamics are used to predict success. The second argument, then, does not apply to VT: no inference based on sensory cues is needed to allow metacognitive prediction. What is stored is a set of predictive cues associated with a cognitive task (the cues may be non-sensory). Their function is to guide epistemic actions. I have called them cognitive affordance-sensings. Why are noetic feelings, at least sometimes, conscious at all? I am currently trying to solve this difficult issue.

.

Hi Joelle. I would like to thank you for popularizing this topic, and also for pushing it in the direction you do. I’m a successful SF author, and I take pride in asking strange questions of experts in strange fields:

Is darkness metacognitive? Or is the darkness cognitive, and the associated epistemic feelings – fear of the dark – metacognitive? But what if you suffer no fear of the dark whatsoever, yet still avoid it when you see it? Doesn’t darkness or blurriness or simply squinting for that matter tell us something about an instance of visual cognition?

Squinting, for instance, is what always tells me I need to see the optometrist (much as darkness tells me to stick to the streetlights). Something is obviously tracking the clarity of my vision then subpersonally cuing squint behaviour which cues conscious awareness of the problem. Is ‘squint behaviour’ metacognitive?

All cognition requires calibrating (selection) to even count as cognition in the first place. Evolution calibrates. Environmental feedback calibrates. Neural feedback calibrates. Once you appreciate that calibrating feedback is integral to all cognition, the question becomes one of when that calibration becomes genuinely ‘metacognitive.’

With darkness, we just assume it’s ‘out there,’ something that we perceive, even though there’s no such ‘thing.’ With uncertainty we typically assume it’s ‘in here,’ a reaction to what we perceive. So we do seem to have an intuitive folk basis for drawing a distinction, but insofar as we are conscious of both, affected by both, and both involve reportable information pertaining to the sufficiency of the information broadcast, it becomes hard to understand what the cognitive distinction is between, ‘I dunno, it’s pretty dark,’ and ‘I dunno, I got a bad feeling,’ aside from grain and modality.

Say we lacked the ability to see darkness, any way to perceive the problem solving limitations of vision, short squinting. Suppose that no matter how dark it was, we (like Anton’s sufferers, perhaps) saw only perfectly illuminated environments, and only had our ‘feeling of squinting’ (FOS) to tell us about any potential limitations, to stick to the street lights. If FOS counts as metacognitive on your account, why not darkness?

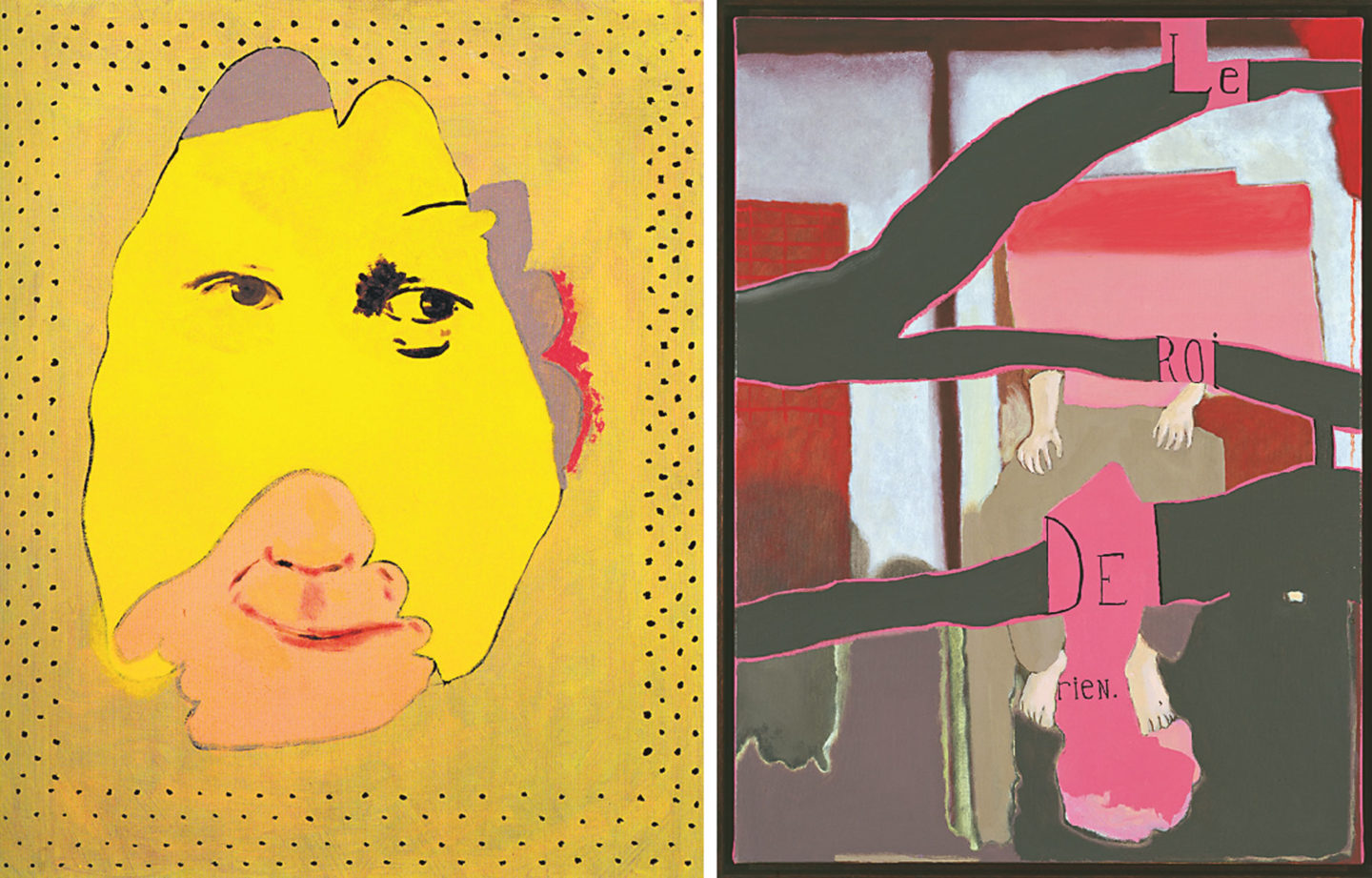

Hi Scott. Thanks for your brilliant comments. It looks, and certainly is, purely coincidental that the author of the trilogy Prince of Nothing, responds to a post featuring an image from the series “le Roi de Rien” by the French artist Jean-Michel Alberola. It is no coincidence, however, if the writer and the painter are both sensitive to the interplay between reflectivity and metacognition. If time allows, I’ll come back to this issue in a future post. For now, Scott, thank you for your “strange questions” (again, a metacognitive assessment). Is darkness metacognitive, or rather cognitive? My responses will follow the order in which your comments are presented.

In children, being in the dark elicits the notion that danger is lurking. From this viewpoint, it is merely an affective attitude where an indeterminate source of risk is sensed (not a metacognitive one). But being in the dark can also be sensed as requiring additional effort to discriminate objects, shapes, etc. From this viewpoint, darkness can elicit metaperceptual evaluations (aka “epistemic affordance-sensings”):” Am I correct that this is location L, object O, property P”?, etc. Finally it can prompt reflective attitudes about the self. “My (in)tolerance to darkness” can be added to the list of the positive or the negative dispositions that are included in the concept of oneself. Darkness, however, is not metacognitive: what is metacognitive is the type of evaluation triggered when having to extract information in the dark.

Relating “darkness behavior” to squinting, as you do, is quite interesting and relevant. Squinting is a way of trying to perceive: it manifests a form of perceptual agency. Whether or not the perceiver is conscious of squinting, her behavior expresses ongoing metacognitive monitoring. For an external observer, or for the agent herself, as you observe, squinting additionally carries information about the perceiver’s competence.

Now, (as I understand your line of argument), does squinting not lead us to a “slippery slope” (ss) argument? If squinting is metacognitive (because it expresses the need for more precise information), what about the photo pupillary reflex, which monitors the amount of light that falls on the eye and controls the size of the pupil? We can resist the pull of this argument: “Information”, here, fails to be the goal of the control subsystem. Its function is rather to protect the eye. More generally: metacognition is defined by its specific function rather than by its control structure. This anti-ss argument works also for calibration. As you observe, there is calibration in all the types of adaptive control mechanisms instantiated in the brain. Vision, audition, cross-modal perception, perceptual confidence, feelings of knowing: all these dispositions are permanently calibrated to remain reliable in spite of developmental or environmental changes. Only the dispositions that aim to control and flexibly adjust to informational value are metacognitive.

Now comes the second part of your comments: “With darkness, we just assume it’s ‘out there’, even though there is no such thing”. Well, why is darkness not ‘out there’ as much as love, food, shelter, are ‘out there’, although they only matter to us, agents with needs and related affects? Are not the absence or paucity of visual information objective relations between a perceiver and her environment, although they are subjectively assessed? Similarly for uncertainty: we assume it’s “in here” and we are right, or rather, nearly right. Uncertainty is felt now, in a given context of action, on the basis of subpersonal predictive processing; but feeling uncertain when we should is the result of years worth of learned, prior, cognitive exercise. Environmental feedback has played a major role in producing a proper (or biased) calibration. Then, in a sense, it’s not merely “in here”.

Your idea of a feeling of squinting (FOS) is very suggestive, thank you for this very helpful thought experiment. Let us imagine that there is no other way for a perceiver to know that her perception is sufficient or insufficient (even in the dark) than having a FOS, just as there is no other way to know that we can or cannot remember, when trying to remember, than having a feeling of knowing (FOK). I would say, in this case, that FOS is metacognitive, and helps control perception and action. This does not make darkness metacognitive, because darkness is the target of what is monitored, not a mechanism that detects and corrects error.

A cool coincidence!

Wonderful response, and persuasive too. The problem is that the conscious experience of darkness truly does render behaviour sensitive to the quality of visual cognition whether or not epistemic feelings are present. When I check on my daughter at night, I slow down or I turn on the hall light. The function pretty clearly seems the same. The point of experiencing darkness (or blurriness, faintness, occlusion, and so on) is to render behaviour sensitive to the quality of visual cognition in given environments.

I see the challenge not so much one of coming up with alternative rationales to the notion that quality pertains to light conditions as opposed to visual cognition, externalizing the epistemic relation, and so transforming the functional description. The problem is that it’s hard to see what could *empirically decide* between things like ‘quality of visual cognition’ and ‘quality of light conditions.’

Hi again Scott,

Thank you for your new comment on the issue of metacognitive mechanisms. To anticipate my response: I am not sure that we carve up personal and subpersonal metacognition at the same joints. We may also have divergent views on the function of explicit (i.e. conscious) metacognition.

Let me first remind you that, from my viewpoint, consciously experiencing darkness does not need to involve metacognition. Hence I don’t share your sense of its raising a problem “that the conscious experience of darkness truly does render behaviour sensitive to the quality of visual cognition whether or not epistemic feelings are present”. One of Robert Hampton’s conditions for metacognition is that the information controlling behaviour should not be present in the first-order stimulus. You can be conditioned to act, on the basis of the incoming stimulus (darkness), in a given way (like switching the light) with no particular assessment of the probability of your failure to perceive in this particular context. The “point” of experiencing darkness etc. (to quote your word) differs across organisms that presumably have this experience. To me, such a point is subjectively captured by an affordance sensing. The latter, however, does not need to be limited to evolution-selected affective programs. Across age and culture, humans associate different affordances to darkness. Furthermore, as demonstrated by the hierarchy of control that characterizes humans’ brain architecture (see the terrific research by Etienne Koechlin), learning does not need to occur merely at the sensorimotor level, although proper control requires commands to reach down to that level in due time. Hence darkness can become a target for metacognitive evaluation, but it may be merely noticed as a cue to press the light switch.

An underlying issue, however, is how “conscious” metacognition (metamemory, metaperception or metareasoning) needs to be to control adequate behaviour. In physical actions, there is evidence that you adjust unconsciously the movements of your arm when a target suddenly moves to a new location, and that you , an expert typist, unconsciously correct your typing errors. Similar unconscious mechanisms are present in the control of cognitive actions. What is, then, the exact role of conscious processing in action control? As Chris Frith claimed in a recent workshop on metacognition (soon on line), “Explicit metacognition is the tip of an iceberg”. On Chris’ view, monitoring elicits conscious metacognitive feelings (such as feelings of knowing, of effort, of being right) only when these feelings have an additional social function, related to communication and verbal justification, for example to convey the strength of one’s knowledge or of one’s motivation to learn.

You may, however, accept all this, and only worry that ‘it’s hard to see what could “empirically decide” between things like “quality of visual cognition” and “quality of light conditions”‘. It should not be ‘too hard’, in my opinion, at least for science: granting that brains have procedures for selecting how to process information (cognitively or metacognitively) in a given context, we should at least in principle be able to track them down (neuroscience offering the most promising methods of investigation). If brains did not have such procedures available, cognitive systems would never (whether subpersonally or personally) know when to recalibrate their confidence assessment, or when the world has changed.

I’m a big fan of Chris Frith as well. I’ll definitely check out Robert Hampton—sounds like fascinating work. One could circumscribe the scope of the definition in all the ways you say, I agree, but the question is what kind of consensus can be gained as a result. The problem is one of chronic, theoretical underdetermination. Where does ‘evaluation’ occur in a supercomplex neurobiological information processing system? There’s always going to be a plethora of ways of reading evaluative functions into complex systems for the same reason it’s so easy to read metacognitive evaluation into darkness. We can use the architecture the way you do here to sort between the intuitive strength of evaluative functional interpretations, but there will always be interpretations that cannot be so sorted, new ways of seeing metacognitive evaluation. The worry is that the philosophy of metacognition will never be sent to the back of the room!

I backed into the question of metacognition, began considering the question biomechanically, as the question of ‘autocognition,’ asking what kind of brain would be required to do what social cognition and metacognition seem to do: cognize brains. The landscape looks quite different from this ‘zombie metacognition’ angle, less interpretative. It seems to me that one can’t inquire into the nature of complex systems such as human cognition without first considering how it is their own brain cognizes complex systems. It does so heuristically, by fastening on cues correlated to the systems to be solved. The cues are generally low-grain, slippery. This is why, as the research of Sherry Turkle or Clifford Nass reveals, we so readily cognize machines as humans. And this is why—it seems clear to me at least—intentional and normative concepts remain perennially controversial.

With respect to the view that self-prediction is conducted through predictive heuristics, the zombie angle does not differ from the scientific angle. At least on this issue, there is wide consensus. Supposing that these heuristics are “low-grained and slippery”, how can one explain that they turn out to be reliable (in a number of contexts)? Why does communication of confidence level among participant improve group performance? Do you consider this to be controversial?

The term “evaluation” may have intuitive meaning, but it captures regularities (prediction/retrodiction-action guidance). As emphasized by Dennett, the value of an intentional strategy is to make the physics of mental states tractable thanks to the mediation of teleological hypotheses. Informational function, on this view, is not based on high-level speculations: it to has to be backed up with evidence from both functional regularities and their neural implementation. If your objection is that there might be many different physics of the brain, and many different views of function, the burden is on you to substantiate this point.

I just want to thank you for bearing with me, Joelle. I’m a bona fide institutional outsider, cursed with alien perspective! The eliminativist has a tall abductive order to fill, I entirely agree. This is the primary reason eliminativists are generally given short shrift, as far as I can tell: they *seem* to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I entirely agree with Dennett that intentional posits have their uses in scientific contexts, but I don’t think he’s clear on what heuristic cognition consists in, and so has no robust way of delimiting ‘problem ecologies.’

I think evaluation talk, like representation talk, needs to come after biomechanical talk. Just consider the apparent ‘knowing without knowing’ paradox pertaining to certain epistemic feelings. Here’s another strange question: Where does the sense of paradoxicality come from? Why should we find the notion of an information processing, behaviour generating system possessing low-grain sensitivities to its own information processing at all problematic–let alone paradoxical? The fact that we do, I would argue, indicates we are running afoul the limits of our tools. Running into paradoxes of this sort is good indicator, I think, that some heuristic boundary has been crossed.

“Supposing that these heuristics are “low-grained and slippery”, how can one explain that they turn out to be reliable (in a number of contexts)? Why does communication of confidence level among participant improve group performance? Do you consider this to be controversial?”

Heuristic systems are low-grained and slippery for the same reason they’re reliable when applied in their respective problem ecologies. They track cues correlated to the systems requiring ‘solution.’ Since the cues themselves don’t belong to the systems, they are easily detached, thus the human propensity to ‘anthropomorphize.’

On my way of looking at things, obliviousness, neglect, is the great cognitive liability, what evolution is always trying to weasel around, and trying to understand cognition absent understanding neglect amounts to attempting to understand weather patterns absent understanding ocean currents. The communication of ‘confidence’ in social cognition plays a role analogous to that of darkness etc. in visual cognition: it renders (group) behaviour sensitive to limitations on access and/or capacity–proof against maladaptive varieties of neglect.

This is a good example, actually, because it provides a way of levelling the ‘pinnacle conceit’ that characterizes so much discussion of metacognition, as if were some kind of summit rather than just another biomechanical interstice in long evolutionary war against blunders.

Hi Scott,

Thanks for your new remarks. I have never been “bearing with you” at all (I am very sorry if I gave you this impression)! Your comments are terrific and get straight to the point. Your “alien perspective” is both refreshing and challenging.

I’d like to comment your impression of an “apparent paradox” being attached to the notion of “feeling of knowing”. This expression, I am happy to admit, is merely a verbal label, a misnomer if you consider that monkeys, who have no concept of knowledge, still seem to have these feelings. I take the term to refer to something like “implicitly predicting the availability of an epistemic affordance presently not available”. As many other feelings, it predicts not an event, but rather a dynamic sequence: failure now, later success likely. This self-prediction occurs at a subpersonal level; with the feeling, a conscious motivation to act emerges. The neuronal architecture of self-prediction is currently actively explored (See Andy Clark’s recent book and his fascinating posts on this blog). Feelings of knowing are partly based on an error signal telling you that you cannot access a memorized item. Other predictive cues, however, are provided by interoceptive representations (for pleasure, displeasure and arousal) and by proprioceptive cues from the facial muscular activity (selected as predictively relevant in feedback from prior cognitive activity). Frowning behavior might anticipate action failure, and have an immediate aversive effect; relaxed zygomatics, tip of the tongue, might reflect anticipation of action success, and have a motivating influence on pursuing the action. In summary, there is no paradox at all about a feeling of knowing associated with a non-retrieved answer. It just is the structure of a predictive experience.

Now, your worry about metacognitive heuristics being “low-grained” seems to be unfair to noetic feelings, even if it applies to other domains of self-knowledge. Bayesian theorists, and cognitive scientists working on affect or on action are happy to recognize that relevance overrules accuracy and completeness in representing the outside world. As for procedural metacognition, however, its activity-dependence, – the fact that the information being used is generated by the task itself (on the background of feedback from prior practice) – makes it myopic, but relevant and precise. Metacognitive heuristics, then, do not easily detach from their operation conditions, although formal education or ritualized epistemic practices expand so much the range of metacognitive monitoring that things may get out of control: fluency can, now and then, wrongly predict truth (see the case of the equality bias reported in this post).

Dear Joëlle,

Thanks for your post and all your replies; this discussion is very interesting.

Reading your previous replies, I got interested to know more about your own view about the relationship between metacognition and consciousness. Some researchers have suggested that metacognitive feelings are necessary conscious (Koriat, 2000), whereas others have strongly claimed that most of the times they are unconscious (Reder & Spehn, 2000). In one of your replies you said that Frith claims that metacognitive feelings only become conscious when they have a social function. What’s your own view on this issue?

Hi Joëlle, thanks a lot for these great outlines of your views on metacognition.

You say that recalibration allows metacognition to be (or become) reliable. I was wondering however what happens when it comes to intuitions about cases we never encounter in real life, eg. intuition about the possibility of a certain zombie scenario or a certain Gettier scenario. Because Gettier cases and zombies are, to say the least, extremely rare in real life, it seems that we will never get a chance to recalibrate our intuitions about them and that the latter will accordingly probably be very unreliable.

Do you support a form of skepticism regarding such intuitions ? More generally, how does your view on metacognition impact the recent debate on the reliability of armchair philosophy ?

Hello Alexandre! Thanks for your two relevant and challenging questions. The issue of calibrating one’s own conceptual intuitions is pressing, because, as we read in Cummins (1998), calibration- a key to proper truth-evaluation – requires gaining access to the putative source of evidence it relies on. Let’s see how it might work, first, for Gettier intuitions. Suppose you are not a philosopher, but a layperson presented for the first time with the hospital case. After all, this case is encountered in life. Hence you may already have formed heuristics associating a number of predictive cues allowing you to discern cases in which you know, or merely believe to know a proposition. The intuitive character of a proposition is presumably a function of how fluent the response is. If it downs on you, a response feels intuitive to you. Gettier intuitions may be universal because they reflect common situations where people are led astray by various features, such as a broken clock or too common a proper name. Calibration of an intuition depends on the variance in the predictability of the cues involved in a heuristic. On this view, then, there is after all an independent source of evidence, because fluency tends to predict truth. This said, in a number of occasions, fluency (including disfluency) takes us away from truth. Hence, presumably, Gettier intuitions are stronger when the meanings of the terms for “believing” and “knowing” do not overlap. This is the case in Sanskrit and Bengali, whose speakers have weaker Gettier intuitions. In contrast, philosophers are trained to think about Gettier cases. They do not respond only on the basis of laypersons’ intuitions. Extensive conceptual learning allows them to detect all kinds of Gettier variants that laypeople cannot; it also changes their sensitivity to what appears to be true. Extensive philosophical practice may also generate intuitions about such improbable creatures as Zombies. Philosophers, just as mathematicians and chess players, have intuitions available that laypersons do not have.

This offers an answer to your second question. Do I support a form of skepticism regarding such intuitions? Global skepticism would be justified if intuitions were mere illusions, and never had a normative-predictive value. Intuitions, however, are positive feelings that signal us that a particular belief is likely to be reliable, or a particular thought to be truth-conducive. They signal something like: “knowledge ahead”. Caution is needed, however, when trusting one’s own intuitions. Claims about race and gender look intuitive to many. Many intuitive responses to classical reasoning problems are dead wrong. In contrast, in areas where thinkers, philosophers or mathematicians, have had the opportunity to perform extensive reasoning and put their concepts to work, intuitions, once recalibrated, might indeed reliably orient a thinker. Hence recalibration is a source of justification for intuitions, when informed by an appropriate feedback. In other terms, intuition in armchair philosophy is only justified when it attaches to dependable concepts.

Hi again, Santiago. Your question is very important, thank you for raising it. Asher Koriat (2000) indeed proposed that noetic feelings need to be conscious to flexibly control behavior. Lynn Reder and colleagues objected that metacognition can control behavior through unconscious feelings: there is evidence for metacognitive control in blindsighters. Note that demonstrating the absence of a conscious feeling is difficult to distinguish from demonstrating the presence of an unconscious feeling. We need an operational definition, including typical bodily cues and electrophysiological measures in addition to verbal report (when available). Alternatively, neuroscientific evidence might offer ways of contrasting the two cases.

If noetic feelings are analyzed as affordance sensings (as I proposed in 2015), it is plausible to speculate that the latter are conscious when specific requirements associated with combining multiple affordances of various intensity and valence. The recent model for interoceptive predictions in the brain, by Lisa Feldman Barrett and W. Kyle Simmons might convert this speculation into a precise hypothesis. In their model, the interoceptive system is claimed to provide efference copies to multiple sensory systems and thus form the basis for unified conscious experience. This hypothetical interoceptive predictive system might convey to multiple brain areas valence gradient and intensity in cognitive affordances through embodied signals. If they are right, nonhumans might have conscious feelings, after all. I intend to refine my analysis of the affordance sensings in the light of this model, in order to account for the conditions that require noetic feelings to be conscious.

Concerning your question about the view defended by Chris Frith, the link to his talk should soon be on line on the second post “How does metacognition work?”

Dear Santiago,

I am now able to complete my reply to your question above about a prior reply to Scott, where I claimed “On Chris Frith’s view, monitoring elicits conscious metacognitive feelings (such as feelings of knowing, of effort, of being right) *only* when these feelings have an additional social function, related to communication and verbal justification, for example to convey the strength of one’s knowledge or of one’s motivation to learn.”

The word “only”, I now recognize, may not quite accurately describe Chris’ view, which he stated in this way in a recent email to me:

“Rather, I defend the view that explicit monitoring is valuable (in some evolutionary sense) because these feelings have a social function. Or perhaps I hold the view ‘that monitoring elicits conscious metacognitive feelings (such as feelings of knowing, of effort, of coherence) because these feelings have an additional social function’. The key question is what predictions do I make? I think I would predict that conscious metacognitive feelings are more likely to arise in social contexts than in non-social contexts. I am not sure how one could test this prediction in practice.”

I am very grateful to Chris for this clarification, and apologize to him and to the readers for having unduly strengthened his claim. Let me correct my former presentation of Chris’ view, then, in the following way: conscious metacognitive feelings might, according to him, exist independently of social contexts; their function, however, is mainly social.

A strong evolutionary point about the function of human conscious noetic feelings (which Chris Frith does not endorse in his comments above) bears on their existence and role in nonhumans; it might suggest that nonhumans do not need to have conscious metacognitive feelings, because they do not have the same communicational needs as humans do.

It’s been argued, however, that nonhumans also need to monitor their uncertainty, both in competitive foraging and in controlling and monitoring their auditory and gestural communication (see my Mind and Language 2016). Do conscious feelings better serve these needs than unconscious ones? It is arguable that conscious feelings might have been selected for in the absence of justificatory goals, and might rather derive their function from their higher efficiency in integrating multiple independent affordances in complex decision-making. Similar considerations might account for the adaptive value of having conscious feelings of other types.