Maybe before plunging into the project I pursue in Varieties, I should say something on the very idea of a first-person, introspectively based project for studying consciousness. In particular, I want to comment on the idea that a crucial step in cognitive science becoming a serious scientific study, no flimsier than organic chemistry or astronomy, was getting rid of any appeal to introspection, subjective data, etc. The comment I want to make is that this is a complete myth: introspection is pervasive in cognitive science, and we’re lucky that it is.

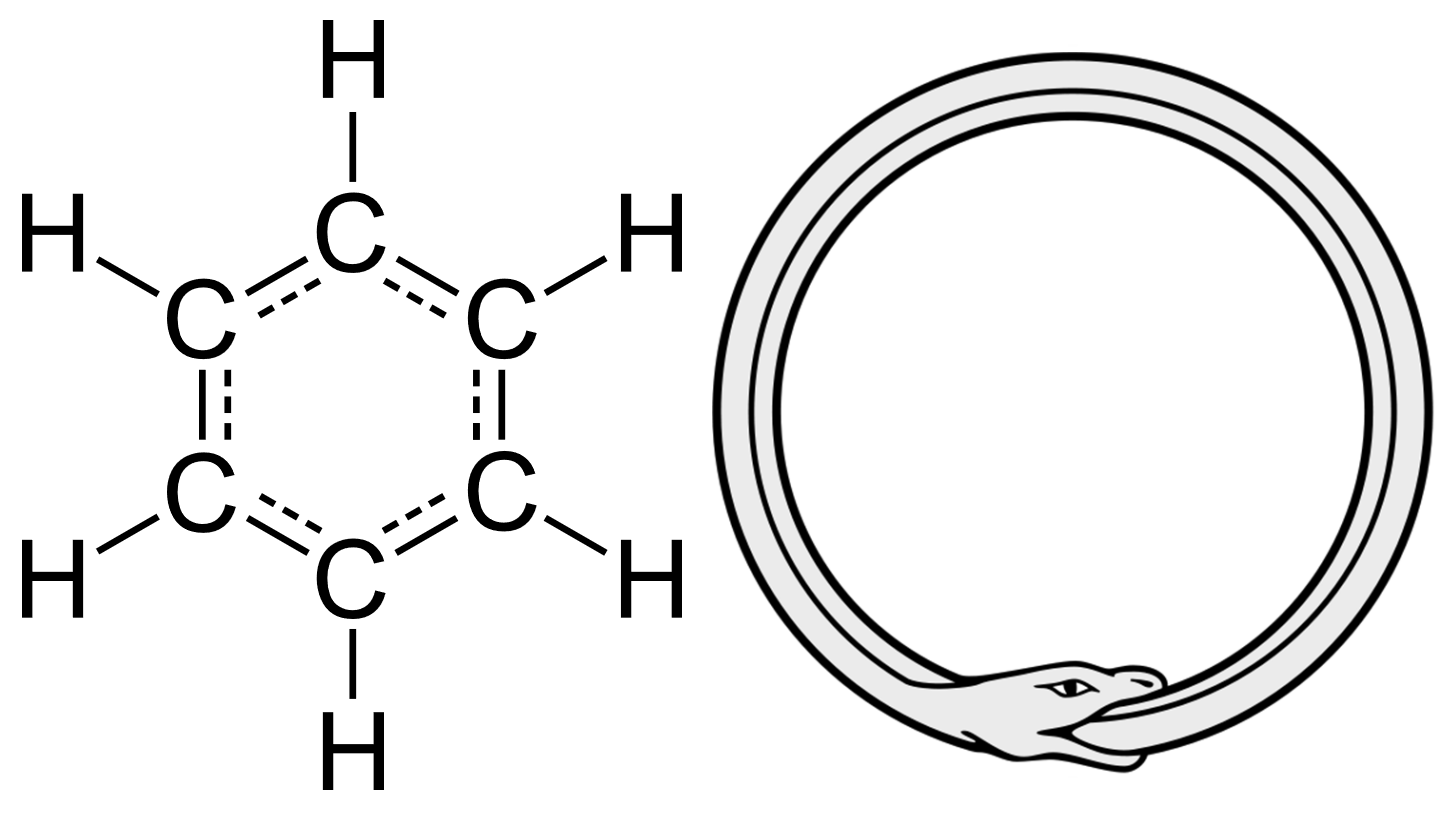

To appreciate the depth of the myth, we should remind ourselves of Reichenbach’s old distinction between “the context of discovery” and “the context of justification.” A nice, clean example is provided by the renowned 19th-century chemist August Kekulé, who discovered (among many things) the structure of benzene molecule. When he was very old, he gave a speech in which he described how he discovered the structure: he couldn’t figure out how all the empirical constraints from what we already knew about benzene could be satisfied by one structure, until one day he dreamt about a snake biting its own tail, and then realized that the benzene must have a similar structure, circling back into itself. However, when he originally published his hypothesis (now widely accepted) in the mid-1860s, he did not write “check this out, I had a dream…” He gave a complicated empirical argument to do with isomers and stuff like that. The point scientific discovery is one thing, scientific justification another.

I point this out because a lot of cognitive science in areas like vision science (i.e., areas implicated in consciousness research) consists in perceptive scientists having introspective insights and then coming up with really cool ways of justifying the insights in introspection-free ways. My impression, from going to cogsci talks about once a week for a dozen years now, is that 80% of what cognitive scientists do in such areas is to devise spectacularly ingenious ways of providing purely third-personal “objective measures” that ratify what they already know based on personal introspection. In many cases, the hypothesis itself is totally obvious from the first-person perspective; where the scientists shows her ingenuity is in devising a way of demonstrating what we already know in an introspection-free way.

This exercise is not without value, but it’s not exactly the same as what happens in organic chemistry and astronomy, where the discoveries themselves are being made with the use of science and technology. There are of course cases where the discoveries themselves are made in a similar way (especially discoveries about brain mechanisms subserving cognitive functions, behavior under extreme conditions of cognitive duress/attentional overload, etc.). But as far as understanding consciousness is concerned, cognitive science rarely discovers anything without appeal to introspection; more often, its concern is to justify what has been partly-introspectively discovered without appealing to introspection.

I like to imagine a possible world where everything is the same up till 1913, but then, after Watson publishes “Psychology as the Behaviorist Views It,” no scientist has ever again appealed to introspection. Maybe, coincidentally, there was some cosmic event that wiped introspective capacity from all humans. How would cognitive science develop over the next century? In some areas, maybe very similarly (or even better!) than it did in the actual world. In the area of consciousness research, I think we would have virtually no scientific knowledge gathered over the following century. I suspect we would not have a global workspace theory, an information integration theory, and all those other cognitive-scientific theories of consciousness we have today; we would not have the gamma synchrony hypothesis, the fronto-parietal network hypothesis, the dlPFC hypothesis, and all those other hypothesis about the neural correlate of consciousness we have today; etc. We would have next to nothing. But in the actual world, we do have all these things. So don’t tell me that cognitive science has rid itself of introspection!

The other comment I wanted to make about all this is that introspection should have its place even in the context of justification, though it shouldn’t be exaggerated. There’s an old Cartesian view that insists on two awesome features of introspection. We can summarize them as follows:

[Infallibile] If introspection says you are having phenomenology P, then you are having P.

[Self-intimating] If you are having phenomenology P, then introspection says you are having P.

Both are implausible, and insisting on them has been disastrous for the reputation of introspection. But consider these two alternative principles:

[Nice to have] If introspection says you are having phenomenology P, then you are more likely to be having P than if it says you’re not having P.

[Pretty cool] If you are having phenomenology P, then you’re more like to introspect having P than if you’re not having P.

My claim is that introspection is pretty cool and nice to have, and that in virtue of being such it meets a minimal standard of reliability. I think of introspection as about as powerful and reliable as my sense of smell. My sense of smell is also pretty cool and nice to have in the above senses: smelling coffee makes it more likely that there’s coffee around and having coffee around makes it more likely that I smell coffee. Importantly, if I had no other sense perception but smell, then even if I were completely incapable of improving my sense of smell, I would totally use it all the time to try to get information about my environment. As it happens, in the actual world introspection is our only mode of access to consciousness, so given its minimal reliability, we should totally use it all the time. Which we have been – so everything’s cool…

Hi Uriah! This post is great. I found myself wanting to push back on some of what you say here, so I got your book and started reading. It has been very helpful. You address many of my initial thoughts in the introduction and in Chapter 3. Two thoughts remain and I wonder what you will say about them. (I have by no means finished the book, so my apologies if my remaining thoughts are fully addressed in the book. My searching and skimming the electronic version did not reveal an answer).

Disagreement

In the 7th section of the introduction, you lay out three reactions to disagreements about phenomenology and address each one. Then you provide a sort of heuristic that recommends one of two reactions depending on the generality/specificity of the phenomenology. You seem to be open to there being additional dimensions that could help determine which approach to take to disagreement. I wanted to float a couple possibilities. First, significance. In cases where the disagreement in phenomenology is significant, we might want to claim that there is a fact of the matter about which side of the disagreement (F or ~F) is correct, but we might not care to claim that either side of disagreement is correct if the disagreement is insignificant.

Another dimension — which seems to follow more naturally from what you say here and in your book — might be reliability. While it might be right that introspection is, in general, minimally reliable, there might be reasons to think that our introspective phenomenology is robustly unreliable in certain contexts. So when people disagree about their introspective phenomenology in one and the same context where introspection is robustly unreliable, then there might be grounds for discounting, perhaps only prima facie, the introspective phenomenology of all parties in that context. I wonder if that seems right to you.

(These thoughts are probably the result of reading and/or talking to Mike Bishop and JD Trout).

Reliabilism & Foundationalism

In Section 10 of the introduction you mention that part of the import of this project is the possibility of phenomenology providing prima facie justification in the “same” (or perhaps just similar) way that perceptual experiences do (Huemer 2001, Pryor 2005, etc.). I am curious whether you would want to embrace other parts of this phenomenal conservatism picture, like some kind of foundationalism. In particular, I wonder whether or not you want to say that epistemic justification bottoms out in introspective phenomenology and/or that introspective phenomenology is an unjustified justifier. (These thoughts are probably the result of Susanna Siegel’s excellent talk at this years SSPP).

Disclosure: I ask because you express the virtue of introspection (here and in your book) in terms of reliability and then you draw the connection with phenomenal conservatism, which might be associated with a kind of foundationalism. And I wonder if reliabilism about introspection might come into conflict with foundationalism about introspection (or just come apart from it) at some point. Does that seem right? Would you want to commit to one or the other? Of course, your answer to this might just follow from what you say about reliability under “Disagreement” (above).

(My apologies for typographical errors.)

Hi Nick –

Thanks for the fun questions. Here are my initial thoughts.

RE disagreement. I like both your ideas. On the matter of significance, I’d just want to distinguish two views. The first is that when an introspective dispute concerns a comparably insignificant issue, there is no first of the matter as to which disputant is right. The second is that there may be such a fact of the matter, but we may not care enough to worry about to much. The second view sounds to me methodologically sound. The first view, in contrast, is implausible: there’s no reason to suspect a correlation between the existence of dispute-settling facts and our degrees of curiosity. On the matter of reliability, I agree that the more reliable introspection in a certain area is, the more we should rely on it. Using this precept requires, however, that we have some independent hold on introspection’s degree of reliability in a given area – which we may not have at the outset of inquiry.

RE foundationalism and phenomenal conservatism. Indeed, I’m very tempted by the thoughts that introspective beliefs are foundational, that is, epistemically justified independently of any other beliefs. Then there’s the question of what other beliefs might be foundational. The most extreme introspetophile view here would be the thesis that only introspective beliefs are foundational. Perhaps this was Descarte’s view. A slightly weaker view is that the only foundational beliefs are a priori logical and mathematical beliefs; in this picture introspective beliefs are the only foudational a posteriori beliefs. A still weaker view allows in also perceptual beliefs. And there are of course views weaker yet aplenty. Two questions that interest me are: 1) what would be the best way to defend the foundational status of introspective beliefs?; 2) what is the minimum we must add to introspective beliefs to be able to justify the rest of our belief system? One day I’d like to get into that…

Hi Uriah! Kneejerk reaction: If, as you say, “in the actual world introspection is our only mode of access to consciousness”, how could we possibly be confident that it was even minimally reliable? (Unless having phenomenology P is partly constituted by introspecting it.)

For example, maybe most brain states are phenomenological states that are introspectively inaccessible, so that most P-types violate [pretty cool]. Do we have any reason at all to think otherwise? If introspection is our only mode of access, we could have no idea of the extent of false negatives.

Hi Dan!

Ah, that’s an interesting option I dogmatically didn’t consider. If phenomenal properties are instantiated by various subpersonal states, then clearly [Pretty cool] is out. I suppose I had in mind that phenomenally conscious subpersonal states are impossible. But I’d need an argument for this.

One thing that pushed me in that direction is my view (defended in an earlier book) that every (phenomenally) conscious state is a state we are aware of, if only very dimly and very peripherally. So, right now I’m looking at my laptop and thinking about the next sentence I’m going to write. That’s what I’m focused on. But in the periphery or margin or background of my conscious experience, I’m also hearing the soft murmur of my dog sleeping, feeling my dully aching ankles, etc. My claim is that, one of the things I am peripherally aware of in this way is my conscious experience itself! The experience is partly an awareness of itself, though typically in a very peripheral way. (I know, that’s super-controversial…)

Now, suppose you have this view. This doesn’t deliver yet that every conscious state is introspected, because the kind of awareness we have of our conscious states is not typically an introspective awareness (I am assuming here that introspective awareness is always focal rather than peripheral). However, there might be an argument for the following plausible-smelling thesis: if subject S is aware of entity X, then it is nomologically possible for S to be focally aware of X. It would then follow that for every conscious state we have, it is nomologically possible for us to introspect it. That is, every conscious state is introspectible. This seems to rule out subpersonal conscious states.

In summary, I need to things in place in order to rule out your scenario. The first is the claim that for every conscious state C of subject S, S is aware of C, if only very dimly. The second is that if S is aware of C, then nomologically-possibly, S is focally aware of C. Both are far from obvious, but I confess I like the sound of them…

I haven’t come across a plausible non-circular argument for the first claim (necessary awareness of conscious states), but I will have to look through your book for one. (I should have read it by now anyway…)

As it is, though, I fear your exploration of the varieties of consciousness will tell us more about the varieties of introspection and/or “dim awareness”. And they may very well have nothing in common beyond the fact that they are potential targets of introspection/awareness…

Hi Dan –

Actually, I haven’t seen a very good argument for the claim about necessary awareness either. I know I personally could never come up with one. As a result, I’ve come to treat this as a kind of “Archimedean point” of my theory of consciousness, an “unmoved mover” of sorts (partly also because it seems like the most obvious thing in the world to me, even though I realize it doesn’t to many people smarter than me). What I ended up doing in my 2009 book is that I collected (what I take to be) the four best arguments for the thesis in an appendix, and presented as the book’s official thesis the conditional claim that if you buy this starting point, then here’s the best theory of consciousness. The appendix then takes a shot at convincing you of the antecedent.

To me, those arguments always seem to use premises that seem to me less obvious than the necessary awareness claim. But if I try to “inhabit” as dialectially neutral a perspective as I can, I think the best argument for the thesis is an argument from memory that was first presented by the Buddhist philosopher Dharmakirti (7th century dude, I think!). I discuss it in my appendix, and there are several other discussions in the literature (my favorites are by Jonardon Ganeri).

On introspection vs dim awareness: yes, I agree with you – in the intro to my book I say that I use “introspection” widely to count that kind of awareness in it too.

Thanks Uriah! Your reply to “Disagreement” seems shrewd. And your clarification about your commitments to foundationalism is helpful. I look forward to reading the rest of the book!

yo.

Do you get into the scope of introspection? That is, in introspection are there some properties we’re especially reliable about but others that we’re not? I would have thought we’re very reliable about sensory phenomenology, in that if we’re in pain or seeing red, we generally know it (or can easily know it, etc.). But what about more controversial properties like the alleged simplicity of sensory qualities? Or that such qualities seem nonfunctional or nonphysical? I take it those are supposed to be introspectible, but I would resist the idea that we have reliable access to them ; indeed, I think we’re systematically wrong about such properties. Do you accept some sort of cut here between the reliably knowable and the not-reliably knowable?

More generally about introspection, I certainly agree that without it there’s not much to talk about here, but what of, say, Dennett’s heterophenomenology? There’s a sense in which he accepts introspective reports and there’s a sense in which he requires the addition of 3rd-personal support. Putting aside issues of “facts of the matter” and whatnot, isn’t it the case that such 3rd-personal support is to be desired if we can get it? I’d say it obviously is, precisely because when it’s lacking, disagreement gets pretty hairy. (I see from your discussion with Nick that there’s lots of this in the book, but I’m trying to learn on the cheap here!)

Finally, one last thingy: do you think introspective data might be theory laden? Maybe the boundaries between phenomenal categories here are pretty vague, leaving lots of slack for (perhaps implicit) theoretical interpretation. Or do you think introspection, unlike perception, say, is more immune to such influence?

Thanks!

Hi Josh –

These are great questions – and big ones.

RE scope. My view is that introspective self-knowledge, unlike other kinds of self-knowledge, is restricted to simultaneously instantiated phenomenal properties. Properties like being nonfunctional or nonphysical are not phenomenal properties. So if someone tells you that their introspection tells them that their consciousness is nonfunctional, their mistaken about the source of that conviction – it’s not introspection speaking. Still, within the realm of phenomenal properties, there are some that are more reliably introspected than others, as you show. One thing that I don’t go into in the book is how to say something systematic about that difference. Another thing I don’t get into is how to draw the introspective/nonintrspective line explicitly and accurately – that’s something I want to work on…

I’m very happy with taking third-person reports that give voice to first-person introspective impressions as part of the data set for descriptive theorizing of the sort I’m interested in. If that’s all there is to heterophenomenology, then I actually engage in the heterophenomenology of freedom in one chapter of my book. I always sensed there was one more thing to heterophenomenology, something less to my liking – but didn’t read Dennett closely enough to think very clearly about that.

The issue of theory-ladenness of introspection is one of the toughest nuts, to me, for the legitimacy of the kind of descriptive first-person project I’m keen on. In particular, there’s this unfortunate tradeoff between the need to train introspection so it carves its subject matter more finely and more accurately, on the one hand, and the need to keep it pure of upstream theoretical preconceptions and expectations. The original introspectionists never figured this one out. One speculative recommendation I make in my book is to try to bridge the gap between introspective acuity and phenomenal subtelty not by tuning up the introspective acuity but by revving up the phenomenal intensity of the experience to be introspected. I pursue this approach with one particular example… But it’s after midnight here in lame Paris, so I shall bid you goodnight for now…

I agree with your claim that vision science uses introspection but disagree with almost everything else you say. So this may be a long winded way of saying that I am not your target audience because I agree with you and so don’t need convincing. Nevertheless I will press on because I am concerned that your argument will fail to be convincing because of the problems I see.

I was quite shocked by your claim that vision science kicks-off from the introspective insights of the practationers (in a context of discovery type way). In my interactions with vision scientists I have drawn the exact opposite conclusion, they often express surprise at what they discover and would like to see your claim backed up by a careful study of the history of some of the discoveries. Off the top of my head here are some other phenomena that are not evident introspectively:

inattentional blindness

change blindness

Some of the more subtle contrast effects (that e.g. depend on perceived shape)

Some of the facts about the structure of our experiences e.g. that blue and yellow are “opposite” colours

What I suspect is most problematic about these phenomena is that they all use subject’s introspective reports and yet don’t seem evident to non-lab based “folk” introspection – as evidenced by expert’s surprise at their findings.

Now this is not to say that the data delivered by such experiemnents is not in some sense based on introspection, it is just not “naive” introspection. Based on the post (and not the book) it worries me that this disagreement could be important to your overall argument because, as Josh suggests, the claim that introspection is not theory laden is an important and controversial one, and if what is discovered by psychophysical “forms” of introspective interrogation is not what is discovered by other forms of introspection then this claim is put under a lot of pressure

I am also a little surprised that you have not looked more at Dennett. His idea is to provide us with a way to collect data from more than one person, and from those who have experiences we cannot, in order to make experiences in some way accessible to those who cannot have them.

Here I think I disagree with Josh’s reading – I think Dennett takes the reports quite literally and does not require any objective test of the subject’s intropsective report. It is used as a way to get at the content of their introspectively available experiences while remaining neutral as to whether such experiences are veridical. The objectivity comes from collating reports, making the experiences accessible without having to had said experience and subtly interrogating them using e.g. psychophysical methods, not from leaving behind “what it is like for the subject”

So I guess I am saying I like the motivation for the project, and am all for “armchair” developments of rich introspective reports, but I think these are different from and should be triangulated with other forms of interrogating experiences. And that they cannot be used in a foundationalist way in our theory building because they are theory-laden and we therefore run the risk of circularity.

Apologies if I have invented and criticised a position that is not yours – I understand there is more much more to a book than the blog posts I am responding to

Hi Liz –

Yeah, really good point re: inattentional blindness etc.

Maybe what I should say about this is that the cognitive scientist used his or her own introspection to come up with the suspicion that the precision and richness or what’s outside the attentional focus of consciousness is far below what we uncritically believe it to be, but just how far below it is was a surprise to everybody. So in this case, the existence of an effect was “discovered” with introspection, but the size of the effect was discovered in the lab. Maybe something like this happens quite often. If so, I should circumscribe a bit more my claim about the role of introspection in the context of discovery.

I should confess, in any case, that I’m offering that claim on a totally speculative basis. To really make the case for it I’d need to do, like, 5 years of research in the “history and sociology of science” applied to cogsci.

I also agree with you, as with Josh, about the importance of naive vs. trained introspection distinction, and all the pitfalls that attend pursuing either. There is sensitivity to this distinction in the book, but that’s not to say that there’s some kind of solution to all the problems it raises. Like I said to Josh, one idea I propose is to use ordinary, untrained introspection to study extraordinary, specially intense instances of a phenomenology (as opposed to using extraordinary, specially trained introspection to study ordinary, relatively mild phenomenology).

I’ve been interested in your work for a couple of years now, and I will definitely be buying a copy of your new book.

One of the things I think you need to consider is simply the kind of biological requirements your ‘introspective nose’ involves. The analogy works, I would contend, because it captures something of the low-dimensionality and the modal specificity of introspective information. But in your 2013 paper, for instance, I’m not convinced you give either angle the kind of consideration it deserves. We have many reasons (such as the metabolic expense of metacognition), I think, to assume that introspection consists of a thoroughly heuristic set of capacities adapted to solving very specialized kinds of problems. This is why introspection is so powerful in certain (largely practical) problem-contexts, and yet disastrously unreliable in others. Introspection, as Bayne puts it in his own response to what you call ‘Schwitzgebel’s Challenge’, has a theory constraining ‘epistemic landscape.’ As Carruther’s has argued, our tendency to chronically, often grossly, misinterpret the deliverances of introspection is itself something that a theory of introspection must explain. Not only is introspection a nose, it’s a nose chronically convinced that it is very cool *at the least.*

I can’t see any way of discharging these constraints that delivers the kinds of introspective deliverances that your account of intentionality, say, requires.

Hi Scott –

Thanks for your input, and for your interest in my work. I confess to limited competence on the relationship between introspection and metabolism. But I like the Carruthers formulation of the problem: we tend to “overinterpret” the deliverances of introspection. This suggests that the deliverances themselves are not to blame, but the post-introspective “processing”… I am developing this approach precisely in a paper I’m currently coauthoring!

I’m keen to see what you come up with. I know Carruther’s position was that deliverances come pre-interpreted as veridical as of a couple years ago. The thing I would stress is that error-signalling is an expense and theoretical metacognition is an exaptation of more specialized systems. The history of philosophy shows there’s some kind of error-signalling problem! It seems hard to believe that such a system could, on the basis of repurposed internal data, warrant making any kind of categorical ontological claim.