In our first post we explained how we came to write The Multiple Realization Book, we articulated our general approach, and we set out our criteria for multiple realization. We also emphasized how our approach demands that we carefully examine scientific evidence for or against multiple realization. Is there good evidence for the multiple realization (realizability) of mental states or cognitive processes?

As we see it, we’re best off approaching this question by way of two more specific ones. First, is empirical evidence even relevant to multiple realizability? Second, what kind of evidence should we be looking for? Obviously, the first question is more basic, for a negative answer entails that the second question rests on a confusion.

While most philosophers would agree that evidence is relevant to the question of actual multiple realization, the question of multiple realizability (i.e., possible multiple realization) is often treated differently. Philosopher Richard Fumerton, hardly atypically, thinks that empirical evidence is beside the point when considering whether mental states are multiply realizable. He says,

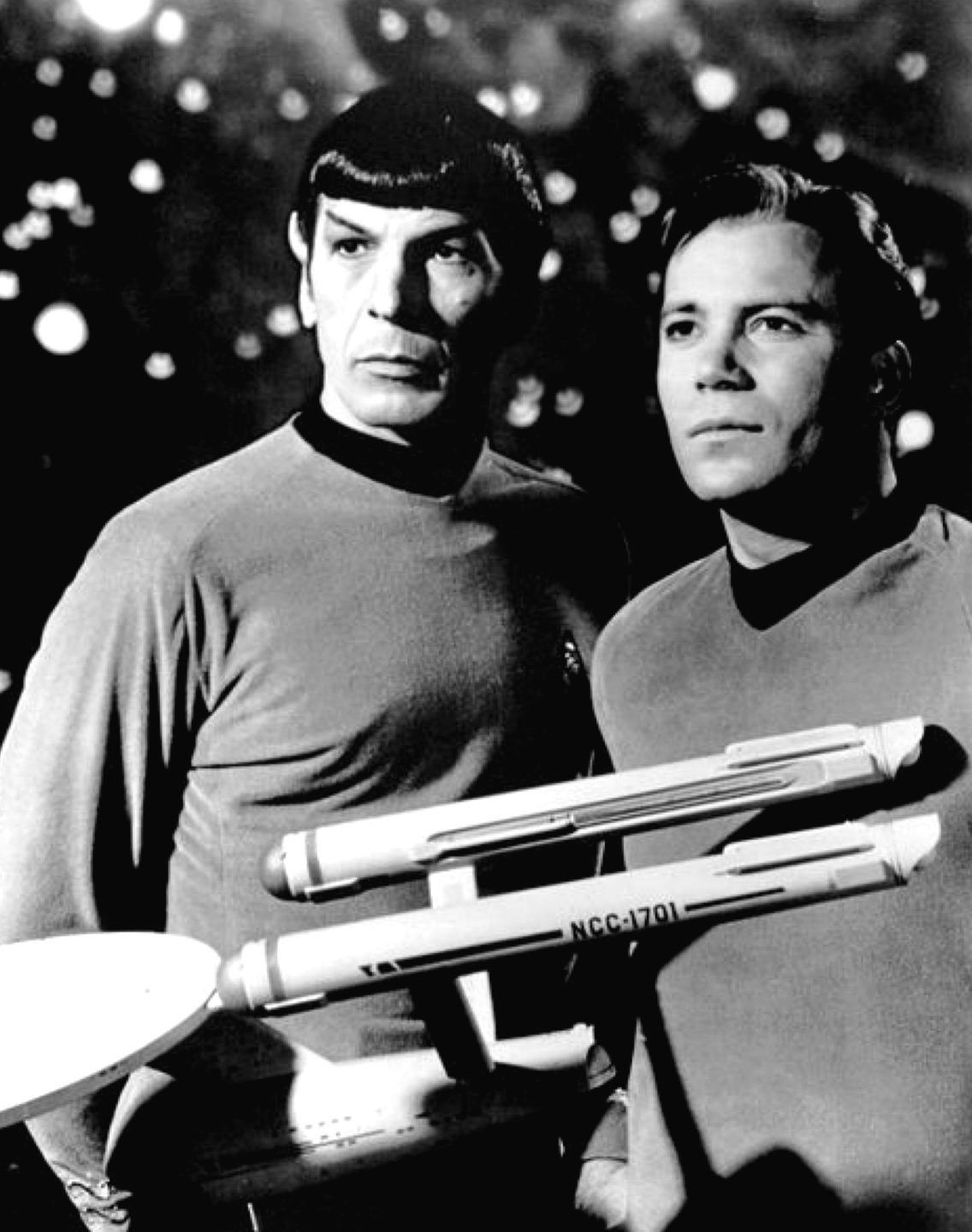

It is hardly the case that the philosopher needed to wait on empirical research to settle the relevant philosophical issues. We would have to be stupid not to realize that it might turn out that creatures with interestingly different kinds of brains could still have the same mental states that we have. We didn’t need to consult cognitive scientists to reflect on the relevant modal question. All we needed to do was watch enough episodes of Star Trek to realize that we had better understand mental states in such a way that it is at least possible for the same mental state to have a radically different base (2007: 60-1).

Fumerton’s point is that interest in multiple realization is merely interest in the metaphysical possibility of multiple realizability. And Fumerton takes the widely shared view that evidence is irrelevant to questions of possibility. While evidence may be relevant to the question of actual multiple realization, the possibility of multiple realization (i.e., multiple realizability) can be known a priori.

On the other hand, Hilary Putnam took quite seriously the empirical credentials of the multiple realizability thesis, arguing that it was the best hypothesis to explain how organisms as diverse as human beings and octopi might all share the same mental state, e.g. hunger. For Putnam, it was important that he was making an empirical claim, because he saw himself as proposing an empirically adequate theory of mind that should be favored over other empirical alternatives, e.g., the identity theory and behaviorism. Putnam didn’t doubt that evidence is relevant to the question of multiple realizability; but he did think that there was evidence of actual multiple realization—and actuality is the best evidence of possibility. So he didn’t think he needed to assess the evidence for non-actual but possible multiple realizability. But that is not to deny that evidence is relevant to deciding which theory of the nature of minds should be preferred.

We thus have, in Fumerton and Putnam, two very different attitudes toward the relevance of evidence for multiple realizability. If the former prevails, we needn’t think about where to look for evidence, because whether any actual multiple realization is discovered says nothing about the metaphysical question of multiple realizability, the answer to which is “Of course.” If we share Putnam’s attitude, evidence is relevant to both actual multiple realization and possible multiple realizability. Our methodological commitments lead us to take Putnam’s side: the choice among competing theories is not a priori, it is sensitive to evidence. So, we maintain that empirical evidence is relevant to whether multiple realization is even metaphysically possible. Given that evidence is relevant, the next question is what that evidence would look like. And it’s here that our criteria come into play.

Any search for such evidence begins with a clear articulation of the phenomenon. (This is not to say that one cannot revise one’s criteria along the way—trial and error. That, after all, is the story of the evolution of our own views.) Whether something counts as evidence for multiple realizability depends on what multiple realization is. Our view is that A and B are multiple realizations of a kind when:

- As and Bs are of the same kind in model or taxonomic system S1;

- As and Bs are of different kinds in model or taxonomic system S2;

- the factors that lead the As and Bs to be differently classified by S2 are among those that lead them to be commonly classified by S1;

- the relevant S2-variation between As and Bs is distinct from the S1 intra-kind variation between As and Bs.

Before explaining how this conception of multiple realization constrains the hunt for evidence, a few points are in order. First, because we follow philosophers like Putnam and Fodor who have seen in multiple realization a suggestion about how levels of science relate to each other, we analyze it in terms of scientific models or taxonomies, i.e. in the explanatory structures of science. Second, we accept that the contents of the world are replete with variation. Multiple realization, we contend, points to a phenomenon distinct from mere variation. The wings of two crows should not count as different ways of realizing the kind ‘wing’ simply because they differ in their number of feathers. (This is one of those trial-and-error lessons about understanding multiple realization that, we think, has been inadequately appreciated.)

Once we’ve characterized multiple realization in terms of models or taxonomies, and have reminded ourselves that not any kind of variation between kinds suffices for multiple realization, the search for evidence can begin. With these metrics, we can examine cases of purported multiple realization and weigh them against the criteria. As should be expected, the cases must be considered individually and handled with care. Some involving, for example, neural plasticity—a very commonly cited “existence proof” of multiple realization—may indeed meet our criteria. But many do not, we argue.

The basic problem is this. Closer examination often reveals that the two cognitive systems are not, in fact, the same according to a psychological taxonomy; or they are the same psychologically, but they do not after all exhibit anything more than “mere variation” (e.g., individual differences) according to a taxomony or model of purported realizers. Finding evidence for multiple realizability is not as easy as most philosophers have assumed.

In our next two posts we first discuss how our criteria work with respect to an interesting case involving mammalian and avian (bird) brains, and next we further explain our commitment to the view that scientific evidence is relevant not only to actual claims of multiple realization but also to modal claims of multiple realizability.

You write, “because we follow philosophers like Putnam and Fodor who have seen in multiple realization a suggestion about how levels of science relate to each other, we analyze it in terms of scientific models or taxonomies”

I know that Fodor, 1974, discusses taxonomies, but does Putnam? If so, where?

Hi Ken,

I can’t say offhand whether Putnam uses the word ‘taxonomy.’ However, it’s clear that he was very concerned with distinguishing between kinds at different scientific levels. This is evident in his early collaborations with Oppenheim and with Kemeny, in their work on reduction. He then abandons the thesis of reductionism, because he thinks that generalizations about kinds at a higher level cannot be captured, via Nagel-style connections, to generalizations concerning kinds at a lower level. His discussion of the peg and the hole exemplify this kind of thinking. I know you think that intuitive examples that don’t traffic in actual scientific kinds are misleading, but the peg and hole are intuitive ways to think about Putnam’s focus on kinds at different levels. We can describe an object as a peg at one level of description, and a swarm of molecules at another. When Tom and I speak about kinds and taxonomies, we have in mind this common practice within the sciences of identifying the kinds that belong in a particular domain (psychology, biology, chemistry, etc.). In the passage of ours you cite, we are drawing attention to this tendency in Putnam and Fodor to understand levels of science as levels of distinct kinds, where the higher level kinds are multiply realized in the lower level kinds. Putnam seems clearly on board with this idea.

Hi, Larry,

So, there is a lot that I find remarkable in this: “because we follow philosophers like Putnam and Fodor who have seen in multiple realization a suggestion about how levels of science relate to each other, we analyze it in terms of scientific models or taxonomies.” First there is the suggestion that Putnam talks of taxonomies. I’ve done text searches of some of the Putnam and can’t find it. But, I could simply have overlooked it.

But, take Oppenheim and Putnam, 1956, “The Unity of Science as a Working Hypothesis,” which I take Fodor, 1974, “Special Sciences (Or: The Disunity of Science as a Working Hypothesis)” to be playing off of. In sections 2. and 3., of O&P, 1956, they articulate levels, in part, by reference to part-whole relations. So, why do you skip this feature of their analysis?

But, there is more. So, there is the question of levels cashed out in terms of part-whole relations or not. Then, there is what does, or does not, stand in these part-whole relations (kinds, individuals, properties, processes). So, there seem to be two issues. How did Putnam understand levels? What are the entities at these levels.

Then, there are questions about your Official Recipe. How does it handle levels and entities?

Ken, there’s a lot here and I’m just getting to it. So three quick comments. First, aside from the playful wording in the title, it’s clear that Fodor’s “Special Sciences” considers a broadly Nagelian view of reduction, not the Oppenheim and Putnam view. Second, I find it remarkable that you find it remarkable that the standard view connects sciences/explanations/models to proprietary kinds/properties, and that the set of them amounts to a taxonomy (“ontology”) for the science/explanation/model. The details vary, but this is standard stuff coming from Quine, Goodman, and Lewis. Third, we hardly talk about levels at all. We can talk about levels if we must, but we don’t rely on a distinction among levels to do any work for us as far as I can tell.

“I find it remarkable that you find it remarkable that the standard view connects sciences/explanations/models to proprietary kinds/properties, and that the set of them amounts to a taxonomy (“ontology”) for the science/explanation/model.”

I don’t find that remarkable. So, you take Fodor and Putnam to be trafficking in levels and that you are following them, but, as you say, you hardly talk about levels at all. That, among other things, seems to me remarkable. Moreover, Putnam in O&P, 1956, were talking about part-whole relations with their account of levels, but you dispense with part-whole relations in your account of levels.

So, let me turn to a more purely philosophical point. So, in TMRB, you discuss one example of plasticity, Sur’s work on the rewiring of ferret cortex. And I take it that this follows from the Block and Fodor cue about brain damage. And, I’m open to concluding that the ferret case is not clear cut. (Pessimism about the case has steered me away from that work as bearing on MR, though I have discussed in with respect to Alva Noe’s theory of perception.) But, there are other kinds of “plasticity” that seem to me more promising.

So, I think it would be surprising had natural selection come upon a mechanism that did a very good job of recovering from such exotic traumas as is involved in the ferret rewiring cases. But, still, (Carl and) I think that it is among the most fundamental features of life that it has to maintain some measure of constancy in the face of diversity. There have to be many, many ways in which, for example, an organ gets pretty much the same thing done in the face of diversity in cell counts. And once you have a theory of how the cells interact, then you might see how the organ can do more or less the same thing given the different numbers of cells. That’s all vague, but think about the vestibulo-ocular reflex. This reflex enables us to stabilize images on the retina during head movements.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vestibulo%E2%80%93ocular_reflex

Ok. Now, from infancy to adulthood, our heads increase in size so the reflex appears to have to adapt (be plastic) in order for it to continue working properly. This seems to be the kind of case one should look to in order to find MR in plasticity. There would seem to be a relatively large amount of evolutionary pressure for a developmental system that matures in a way to make something more or less constant, given more or less diversity.

So, my point is that you seem to be dismissing a broad category of possible evidence after examining what would seem to be a not very promising example.

I guess, for us, there are at least two questions about your “compensatory adjustments” cases. The second would be how prevalent they are. But the first and more pressing question is whether that kind of variation in nature has been thought to block reduction and thereby justify the legitimacy of multiple explanations/sciences/models. I’ll venture to say no. And according to us, that’s the job of MR. So that kind of variation is not MR.

I would guess that you disagree with us about whether it’s the job of MR to block reduction and justify the special sciences. This could be a verbal dispute about what counts as “multiple realization.” But maybe you actually agree with us that it was wrong for, viz., Fodor, to make that the job of MR.

So, you, Larry, Carl, and I all agree, roughly speaking, that for MR there has to be sameness of the realized and diversity of the realizers. My point is that the ferret rewiring case is less likely to satisfy your conditions i) and ii) than are other cases of plasticity. In the ferret rewiring cases, I conjecture, there may be fewer or weaker mechanisms for producing sameness in the face of diversity than there are in, say, than there are in the VO-reflex cases. The evolutionary selection pressures on the ferret brain may not be such as to enable it to recover from rewiring, but the evolutionary selection pressures on the VO-reflex may be such as to enable it to keep sameness of the realized through a diversity of the realizers through time. The VO-reflex case seems to me more likely to satisfy your i) and ii) than is the ferret rewiring case.

As far as I can tell, my point stands even if, even forbid, you had never heard of the Aizawa-Gillett approach to MR.

So, you, Larry, Carl, and I all agree, roughly speaking, that for MR there has to be sameness of the realized and diversity of the realizers. My point is that the ferret rewiring case is less likely to satisfy your conditions i) and ii) than are other cases of plasticity. In the ferret rewiring cases, I conjecture, there may be fewer or weaker mechanisms for producing sameness in the face of diversity than there are in, say, than there are in the VO-reflex cases. The evolutionary selection pressures on the ferret brain may not be such as to enable it to recover from rewiring, but the evolutionary selection pressures on the VO-reflex may be such as to enable it to keep sameness of the realized through a diversity of the realizers through time. The VO-reflex case seems to me more likely to satisfy your i) and ii) than is the ferret rewiring case.

As far as I can tell, my point stands even if, heaven forbid, you had never heard of the Aizawa-Gillett approach to MR.

Here is an outline of my point. In TMRB, you look at one example of plasticity and find it unimpressive. One simple reply is that, look, you may be extrapolating from one unrepresentative case to all cases. I take my point to be more sophisticated than that. I suggest, in addition, how it is unrepresentative. It is a case that is less likely to have mechanisms sufficient unto rendering sameness of the realized in the fact of diversity of the realizers.

Yes, our discussion of plasticity is weaker if our examples are not representative. In fact we discuss several examples of plasticity, and more in other papers. But now you’re you’re moving on to a second argument, about the likelihood of MR given evolution. This is the second of the three arguments from Block and Fodor that we take up. In short, evolution produces all sorts of stuff, so we would not generally predict convergence that satisfies our criteria–though of course it occurs.