I am pleased to announce that our next Mind & Language symposium is on Wayne Wu’s “Against Division: Consciousness, Information and the Visual Streams,” from the journal’s September 2014 issue, with commentaries by David Kaplan (Macquarie), Pete Mandik (William Paterson), and Thomas Schenk (Erlangen-Nuremberg).

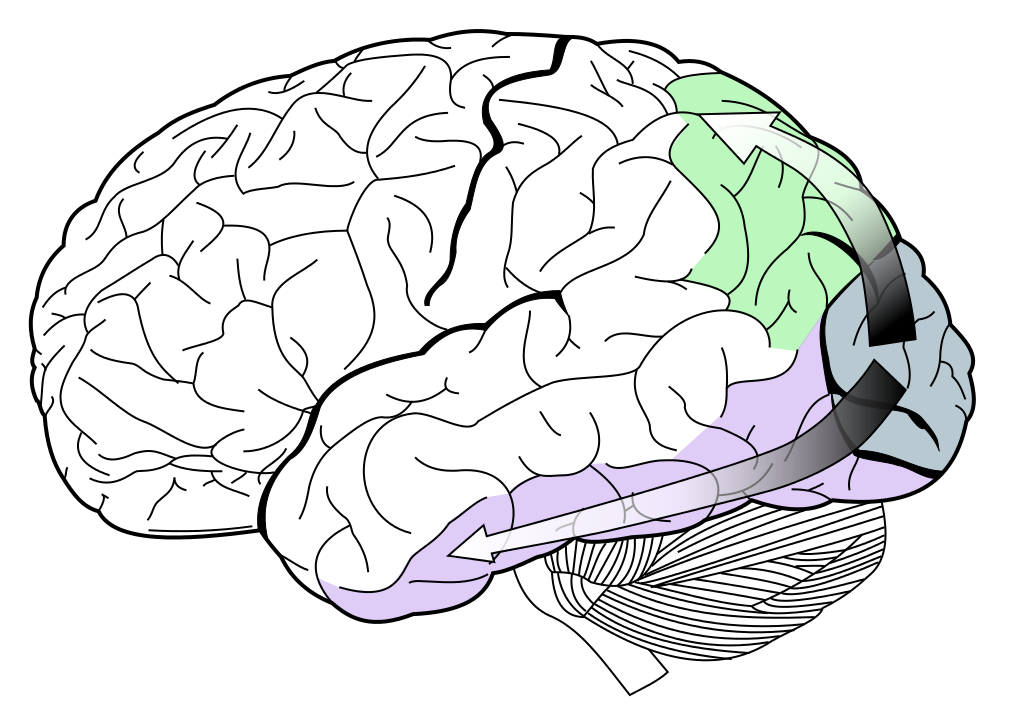

According to the influential dual systems model of visual processing (Milner & Goodale 1995/2006, Goodale & Milner 2004), information present in the dorsal processing stream does not contribute to the specific contents of conscious visual experience. “Visual phenomenology,” A.D. Milner and Melvyn Goodale write, “can arise only from processing in the ventral stream, processing that we have linked with recognition and perception…. Visual-processing modules in the dorsal stream, despite the complex computations demanded by their role in the control of action, are not normally available to awareness” (Milner & Goodale 1995/2006, 202). In his article, Wayne argues that certain types of information arising in the dorsal stream, contrary to Milner and Goodale, do play a role in realizing the contents of visual experience. In particular, he argues that information carried in dorsal stream areas such as VIP and LIP support awareness of visual spatial constancy across saccadic eye-movements. Wayne also adduces evidence that dorsal stream areas play a role in conscious visual motion and depth perception.

According to the influential dual systems model of visual processing (Milner & Goodale 1995/2006, Goodale & Milner 2004), information present in the dorsal processing stream does not contribute to the specific contents of conscious visual experience. “Visual phenomenology,” A.D. Milner and Melvyn Goodale write, “can arise only from processing in the ventral stream, processing that we have linked with recognition and perception…. Visual-processing modules in the dorsal stream, despite the complex computations demanded by their role in the control of action, are not normally available to awareness” (Milner & Goodale 1995/2006, 202). In his article, Wayne argues that certain types of information arising in the dorsal stream, contrary to Milner and Goodale, do play a role in realizing the contents of visual experience. In particular, he argues that information carried in dorsal stream areas such as VIP and LIP support awareness of visual spatial constancy across saccadic eye-movements. Wayne also adduces evidence that dorsal stream areas play a role in conscious visual motion and depth perception.

Below there are links to a short précis, the target article, commentaries, and Wayne’s replies.

Comments on this post will be open for at least a couple of weeks. Many thanks to Wayne, David, Pete, and Thomas for what is sure to be a great discussion. Thanks also to Sam Guttenplan, the other Minds & Language editors, and the staff at Wiley-Blackwell for their continued support of these symposia.

You can learn more about Wayne and his work here.

***

Wayne Wu, Précis of the target article

Wayne Wu, “Against Division: Consciousness, Information and the Visual Streams”

Commentaries:

- David Kaplan, “Can neuronal reference frames really explain features of conscious visual experience?”

- Pete Mandik, “What’s it like when your eyes move?”

- Thomas Schenk, “Can visual stability resolve the division between ventral and dorsal streams?”

Replies:

- Wayne Wu, Reply to Kaplan

- Wayne Wu, Reply to Mandik

- Wayne Wu, Reply to Schenk

As time is short, just a quick note about the main theme of discussion and the relevant parts of the article. The central issues in the commentary concern the nature of visual spatial constancy and the idea of a neural basis for this pervasive aspect of visual experience. To that end, the general comment provides an overview for those who don’t have time to read the article. It should give you the basics, but if you want more, then pp. 390-5 (sections 3-4) then pp. 397-402 (section 6). The paper gives an account of the experience of spatial constancy, argues against one standard explanation, and provides a different one informed by our understanding of egocentric spatial content in the visual system. While the issue of the dual visual streams engaged the commentators less, I am happy to talk about that issue in the comments. Again, my thanks to the commentators, thanks to Robert for driving this through, to M&L for making the article available for free, and thanks in advance to you participants.

Hi Wayne,

Thanks for a very interesting and illuminating paper.

Your view seems to imply that some egocentric contents centered on different body parts are jointly phenomenally conscious (am I right?). I would like to voice a concern about this (which might be off-track, as much of this stuff is new to me).

Philosophers sometimes understand egocentric content as content that is evaluated relative to centered worlds. So, for example, the centered content, “there is a cat straight ahead” is true (let us suppose) when evaluated with respect to the actual world centered on my torso, but false when evaluated with respect to the actual world centered on my eyes. The content “there is a cat below” is true with respect to the actual world centered on my eyes, but false with respect to the actual world centered on my torso. The important point is that such centered contents do not incorporate the torso or the eyes as constituents. These content do not have the form of “there is a cat below *the eyes*”, but rather “there is a cat below”. This, I take it, is supposed to reflect the idea that centered content places objects relative to the center of a coordinate system, but the content does not place the center itself anywhere (specifically, the content does not specify whether center is the eyes or the torso).

If this is right, and if, as you appear to suggest, we visually consciously experience various egocentric contents centered on different body parts, then it appears that our visual conscious experience involves conflicting contents. In the example above, the cat would appear to be simultaneously straight ahead and below. In light of this, I have a suspicion that we cannot consciously visually experience the world through several different egocentric frames of reference at the same time.

This worry does not arise if these egocentric contents are unconscious and serve only motor mechanisms (as in the “two separate visual streams” story), because (arguably) motor mechanisms such as those responsible for calculating movements of the arm, receive only information centered on the arm; they don’t access information centered on the eyes. Hence they don’t receive conflicting information.

Hi Assaf:

Thanks for that great comment! This nicely pushes the issue forward, asking how to specify egocentric content in experience. I think more work is needed on this, and I’m not fully sure the best way to respond. Here goes:

In the general comment or maybe the comment to Schenk, I mention how egocentric spatial experience might be different between touch and sight in that the “origin” is plausibly experienced in touch, at least in certain cases, whereas in vision (for the eye-centered origin), it is plausibly not, except in exceptional cases (looking in a mirror). For in touch, I often experience the body doing the touching just as I experience the object, say when I haptically explore an object. No such “appearance” of the body figures normally in vision. This seems to be an important part of the spatial phenomenology of both modalities worth keeping in mind.

I’m less sure how much weight to put on contradictory content except if we think that (a) a theory of experience imputes it in the experience and (b) the phenomenology doesn’t have that appearance. Then, the theory might be in trouble (I actually argue in favor of unconscious representations in the dorsal stream in a paper called “The Case for Zombie Action” using this sort of conflict in response to Chris Mole’s discussion of embodied demonstratives and the visual streams [https://philpapers.org/rec/WUTCF-2]).

I think your argument is as follows

1. Assume that all body-centered visual frames are visually conscious (me?).

2. Assume a centered-worlds specification of content, along your lines.

3. Assume that we are having a veridical spatial experience.

4. Then the experience presents the cat as both straight ahead and below.

5. This is an inconsistent content, but not reflected in the visual experience.

This then puts pressure on (1). On (1): I’m not sure I’m committed to that. What I am committed to is the following: if I have a visual experience of constancy, then experience reflects a constant egocentric spatial relation. It doesn’t follow that all egocentric relations are present in consciousness. At the same time, nothing rules out your reading and perhaps parsimony suggests that there’s not gating of reference frames into experience to avoid your problem. That is, all reference frames should figure. Still, it could be that how the brain works is that it makes constant egocentric relations salient (i.e. drives attention and experience).

A few quick points: introspection, multimodal sources, and attention.

There is a nagging worry I have about how much weight to put on the absence of contradictory appearances (even though I rely on it myself!). In a review of Eric Schwitzgebel’s book on introspection, Sebastian Watzl and I have argued [https://philpapers.org/rec/WATMRO] that while Eric is right that we often miss many features of experience during introspection, many of these cases are due to insufficient attention in introspection. Perhaps in your case, that contradictory content is there but hard to make it apparent because it requires a very difficult deployment of attention.

A second response is that ultimately, the egocentric features of experience might be only accountable as a multimodal feature of experience. So, seeing something as straight ahead or as below is visually apparent, but only because it is proprioceptively-visually apparent (something like that). Maybe what egocentricity has to teach us is the limits of dividing the senses too sharply (see reply to Schenk).

Pulling these strands together: it might be that the contradictory content is there but that given how we attend to egocentric features, that contradiction can’t be made apparent. For to see the cat as below (my eyes) I have to attend across two modalities, one that yields the body say via proprioception along with one that yields the cat. This is an inchoate thought. Just thinking on my feet a little.

So, let me raise a few questions to get you (and other interested parties) to say more:

1. Why not argue that indeed, the origins of the various reference frames are part of the contents of experience?

2. This is tied with the following: Let’s say I’m right about the differing phenomenologies in touch and vision with respect to egocentric experience. How is that difference best captured in a centered-worlds picture? For sometimes, the origins do figure (touch).

Hi Wayne,

I just wanted to ask quickly what you think psychophysics and behavioral studies have to tell us about the reference frame (or frames) used in visual experience. A lot of people argue on the basis of such evidence that apparent visual direction is direction with respect to the so-called cyclopean eye. (Hering 1879, Bridgeman & Stark 1991, Ebenholtz 2001, and Ono & Wade 2012, for example.) The cyclopean eye is a point midway between the eyes, so such evidence would presumably support a head-centric view of apparent visual direction.

On the other hand, I’m sympathetic to the idea of multimodal visuo-proprioceptive experience and multiple body-centered reference frames. I discuss this a little in a couple papers of mine. I think torso-centered accounts like Peacocke’s can be interpreted without too much strain as involving such experience. Peacocke has told me, however, that he thinks the choice of origin for the reference frame used to specify the content of visual experience is essentially arbitrary so long as it is in the body.

Hi Robert:

Thanks for this. I certainly think behavioral/psychophysical experiments can give us evidence regarding reference frame. In the end, I’d like a neural correlate which is why I like the visual system here as there are various places that are thought to have body-dependent receptive fields. Spatial constancy was promising given not just the behavioral/psychophysics but also the wealth of electrophysiology data.

It’s interesting that Peacocke speaks of the specification of origin as arbitrary, at least in conversation. This links to Assaf’s query So, let me distill the issue to a few questions

1. Is specification of egocentric origin arbitrary for a given experience? If not, what are the constraints?

2. Is the specification multimodal (sensitive to multimodal sources)?

3. How does one account for multiple egocentric origins in a multimodal experience?

Do say more about the papers you mentioned (totally appropriate and likely helpful). Also, further thoughts?

Hi Wayne,

Thanks for the detailed and thoughtful response. Your raise a lot of interesting issues, but for the time being I will focus only on the two questions you raise at the end.

I take it that the first question (when spelled out more precisely) concerns whether an origin of a reference frame can be part of an egocentric content of experience that centers on it, given a centered-world account of egocentric contents. For example, the question is whether the torso can in principle be a part of the egocentric content centered on the torso. In my previous comment my answer to this question was negative. But in light of your touch example, it now occurs to me that it might be possible for my argument to go through, even if the answer to the question is positive. I can grant that, e.g., the torso is a part of the egocentric content centered on it, *but* add that this content must place the torso at coordinates [0,0,0] (I simplify by treating the torso as a volumeless point). The egocentric content centered on the torso cannot place the torso at some location relative to, e.g., the head (for prima facie obvious reasons, but perhaps this could be challenged).

And now, apparently (but I may be wrong here), we get results similar to the cat situation from my previous post: The egocentric content “the torso is at [0,0,0]” is true relative to the actual world centered on my torso but false relative to the actual world centered on my eyes. Analogously, the content (say) “the torso is at [0,-30,0]” is true with respect to the actual world centered on my eyes but false with respect to the actual world centered on my torso. So assuming we consciously, visually experience both contents, the result is that we consciously experience the torso as being at [0,0,0] and at [0,-30,0] at the same time, which is contradictory (or so it seems).

This provides a straightforward answer to your second question as well: the (modified) centered-world picture is compatible with the claim that the visual content centered on the eyes does not include the origin, while the touch content centered on, say, the finger, includes the finger at location [0,0,0]. Does that make sense?

Hi Assaf: I’ve posted a reply as a new comment, due to the indentation feature of the blog which makes things hard to read.

Hi Assaf

Good. So I think we can state the matters as follows. First, if you accept my theory of visual spatial constancy, then what this commits you to is that whenever an object visually appears to you as spatially constant, that constancy is explained relative to there being one egocentric reference frame where over the time in question, the object does not change position relative to that frame. This is literally spatial constancy within a reference frame and the spatial content must be part of experience. Since different reference frames might across time serve different experiences of constancy, say head versus torso, the model is committed to each frame in principle informing visual experience.

The crucial point is whether at a given time, two of these reference frames can be present in visual experience, choose any two that give rise to the worry you have.

At this point, I think many options are open and the point to areas needing further exploration. Here are four:

(1) Does attention play a critical role here in that it gates what we experience in these cases that avoids the potential for contradictory content?

(2) is the contradictory content there and just hard to have in view, perhaps because this requires a special deployment of attention to the appearances?

(3) Does this show that our specification of perceptual content in these cases is in some way inadequate to capture the specific phenomenology?

(4) Might the experience be multimodal in a way that also puts pressure on our ways of thinking about content, driven in part by thinking of the issue as purely visual or tactile or proprioceptive?

I suspect that there are multiple factors here that we theoreticians of experience haven’t fully grasped yet, but I’d be interested in hearing other opinions. I do think that given the nature of the neural processing, there has to be some multimodal factor here and that it is unclear how best to accommodate that and to move away from a purely visuocentric way of thinking. Casey O’Callaghan’s work here is useful.

I don’t mean you to answer those four questions but your reflections help to sharpen the issues so as to identify them.

One small quibble on the extension of your argument, which points to the issue of touch versus vision. I don’t think you’d have the [0,-30,0] content where this captures the torso as part of the visual content (riffing on the touch case). The touch case motivates putting the body part within the content, as you do in your extrapolation, where this is to capture the idea that the body part is part of the experience, is itself experienced (I often feel my hand when haptically exploring an object because I feel the object pressing against my hand). But in the relevant case, the torso won’t be seen, and I think this is the simplest way of reading “[0, -30, 0]” if we analogize from the touch case (e.g. the hand at [0, 0, 0] in a tactile experience that is hand centered also figures as an object in the experience).

Hi Wayne,

I wonder how you would judge the retinoid model of egocentric representation in relation to your own suggestions. You can see an overview of the retinoid model in my article “Space, self, and the theater of consciousness”, here:

https://people.umass.edu/trehub

Hi Arnold:

Thanks for the note. I’m a bit tied up at a conference this week so not sure I will be able to digest a paper right now.

Would you mind, if possible, giving a short summary of how you would deal with the phenomenon of spatial constancy or how our models might differ in some fundamental respect? We can then have an exchange about that which I would look forward to.

Hi Wayne,

thank you very much for the very interesting paper and discussion.

I am a bit puzzled by your reply to Schenk, probably because I haven’t been careful enough in reading the paper and the reply. In any case I hope you can help me.

The problem arise from my understanding of your model where visual information from other body part seems to be required to explain spatial constancy. It seems to me, and you seem to accept this, that we sometimes lack such information. In those cases one might appeal to multimodal factors. Now, although I totally agree with you that “It is not, then, the job of the theory of visual spatial constancy

or inconstancy to explain the non-visual aspects of the experience.”, it might be the case that the visual content of our experience originates (causally or otherwise) in non visual aspects. In this case they should be incorporated in our theory of visual spatial constancy. If such multimodal elements were sufficient for explaining the phenomenon, then we do not need to appeal to other visual elements like the head-centered frame, right?

I also like the point raised by Assaf very much. I would like to hear you opinion (as well as Assaf or anyone interested) about a possible alternative to check whether I have missed something important. The explanandum is visual spatial constancy, which is explained by means of de hic content: the content of my visual experience is centered at a certain location, something like “there is such and such from here”. Now, the alternative reply is that there might be unconscious (visual) representations centered at different points of the body, say head and the eyes. Our cognitive system on the basis of these representations can compute a new one (the conscious one) depending on such differences, whose correctness conditions depend on a “thicker point”, a “thicker here” (a bit more formally, the representation would be correct or incorrect relative to any frame of reference within a certain area and not just relative to a point). Much more need to be said, of course, but this seems to be very much in accordance with what you said (or at least with what I understood) in the paper. However, you didn’t mention this as a possible reply to Assaf and I was wondering if there is any reason for that.

Hi Miguel

Thanks for the reply. I’m going to be a bit slower on replying as I’m on my way to a conference, but I will try to keep up.

First, Just a quick note on the first of your two points. I don’t see that acknowledging the multimodal aspects of visual spatial constancy means that the visual will have no role to play in the explanation. After all, it is still the seen object that remains spatially constant. The central issue is how to understand the way the body presents itself as part of what seems to be dominantly visual experience. That’s why I appealed to a multimodal source since the body part that centers the egocentric content is, typically, not seen.

I think that the multimodality has to be true at the level of computation of spatial information in egocentric (body-centered) frames, and that it isn’t the visual system that provides information about the location of the body even if visual neurons have that information. The way to incorporate this multimodality at the phenomenal level is more challenging.

I would think that the visual aspects of consciousness cannot originate entirely from non-visual aspects. But do say more if I’m not tracking.

On the second point, I think what you say is consistent with my view, but I’m curious whether you could say a bit more about it, perhaps as a means of replying to Assaf’s challenge. There’s something to this idea, I think, in that it connects to an old paper of mine that is now gathering dust in an old hard drive, but is connected to the question of integrating the body in a multimodal egocentric experience of space. There are lots of people out there who have thought a lot about this (Robert and John are among them, and I suspect Matt Fulkerson, Frederique de Vignemont and other will have more to say too). Perhaps they will say some of this! 😉

Hi Miguel and Wayne (Pete, this is relevant to your comment too),

Here is how I understand Miguel’s suggested response to my challenge. Visual representations centered on the torso, head or eyes are unconscious. Hence the cat in my example is not consciously represented as both straight ahead and below. Furthermore, the conscious content responsible for spatial constancy has a more abstract nature, involving a “thicker here”, taking into account the aforementioned unconscious contents. On Wayne’s view, a constant representation of an object’s location relative to some egocentric frame of reference accounts for spatial constancy. This suggests to me that Miguel’s hypothesized conscious abstract content *existentially quantifies* over centers and locations. In this way specific locations relative to centers (such as “straight ahead” or “below”) are avoided. The content therefore should be something like “there is a point P inside the ‘thick here’, such that the location of object O is constant over time relative to P”. Miguel, is this close to what you had in mind?

My first response to this is to note that a visual representation with this abstract content represents the object’s location *as constant*. This is something Wayne (in the précis and in his response to Pete) explicitly rejects. He holds that spatial constancy is a matter of a constant representation of a location of an object, not a representation of the constancy of an object’s location. He calls the former a “deflationary” account (of spatial constancy) and the latter “substantive”. In short: Miguel’s suggestion appears to imply a substantive account of spatial constancy, which Wayne rejects.

To clarify (I’m less confident about the following): Miguel’s suggestion (appears to me to) involve a representation of the property of constancy because his idea (I take it) is to avoid conscious representations of specific (egocentric) locations. If one avoids conscious representations of specific locations, then one cannot have a constant conscious representation of a location over time. At most, one can have a constant conscious representation with the abstract content “there is a point P (in the ‘thick here’) and there is a location L, relative to P, such that object O is at L”. This content is trivially true across time for any object, even if it is *moving relative to all bodily frames of reference*, since a moving object, at any given time, is at *some* location relative to *some* point in the “thick here”. Hence constancy of a representation with this content cannot account for spatial constancy. (I realize that this is quick and complex, so it’s likely I have made a mistake or overlooked something.)

Incidentally, it might be possible to turn the dialectic here on its head: Pete has accused Wayne of accepting the substantive account without ruling out the deflationary account. Wayne responded by saying he had accepted the deflationary account all along. Miguel’s suggestion, if it works, might provide a reason against the deflationary account.

This is one reply to Miguel and Assaf’s recent comments. I’m still traveling so will have to be relatively terse (which is a good thing for me!).

I want to emphasize the phenomenally different ways that touch and vision are egocentric and this is relevant to the current issues. I have an old paper that has been rejected so many times, it now sits discarded, but it was an attempt to grapple with the notion of a perceptual field given this different egocentric aspect. The basic idea is to note that in touch, the egocenter is experienced within touch but in vision, it is not qua egocenter. I actually think that existentially quantified content is the way to do it, and it’s great to be reminded of this.

That said, I don’t see that you have to represent constancy as such in visual content. You can say: there is an x where visible object O is L from x. So long as this content is constant over time, you have my deflationary view.

This doesn’t mean that the body is unconscious per se, only that the egocenter doesn’t figure in a singular content in vision as it does in touch. So, one might begin to get at the distinction between touch and vision in this way, if one wanted to talk about the representational egocentric content as a first pass.

Hi Wayne,

In the retinoid model the body envelope contains the most intimate part of egocentric space. Is this also the case in your model?

Hi Arnold.

Waiting for a plane and saw your reply. Thanks.

I’m not sure; it depends on what you mean by “body envelope” and “intimate part!” You obviously mean more than that the body figures as the center of any egocentric representation which would be the minimal condition for any body-centered representation. I do think, though in a way that would be harder to articulate concisely, that the body as as whole does ground our multimodal experience of space, and that the different aspects of experience that we can isolate via attention highlight different parts of the body. So if “body envelope” means something like a larger part of the body than a part or point, then perhaps? But could you say more about the technical terminology here?

Hi Wayne,

By “body envelope” I mean everything within one’s skin. Body space is a part of egocentric space so I don’t consider the body as such to be the perspectival origin of egocentric space. For example, if you bang your left thumb with a hammer the pain is in your left thumb, and if your left hand is hanging at your side the pain will be to your left, but if you grasp your right shoulder with your lft hand the pain in your left thumb will be to the right of you. So the locus of origin of egocentric space – you – is not your whole body. In the retinoid model of consciousness the locus of perspectival origin (I!) is a compact neuronal cluster in a particular kind of 3D neuronal structure, retinoid space. For more about this see “Where Am I? Redux” and “A Foundation for the Scientific Study of Consciousness” on my Research Gate page.

Thanks Arnold. Sorry for the long delay as I’ve been traveling. One wants to understand the identity claim, namely that the locus of the origin is a compact neural cluster. When you say origin, do you mean that “phenomenall” the experienced origin? If so, then a further question is how exactly a neural cluster meeting your conditions will illuminate that. If you mean the neural realization of the egocenter, then great, do you have more specific areas in mind?

Hi Wayne,

You asked “When you say origin, do you mean that “phenomenall” the experienced origin?”

In the retinoid model of consciousness the perspectival origin of egocentric space is both the experienced origin and the neuronal origin based on its functional role in the 3D spatiotopic structure and dynamics of retinoid space.

Yes, I do mean that this cluster of autaptic neurons is the neuronal realization of the egocenter, which I symbolize as I!. The parietal cortex and the colliculus seem to be two promising brain areas for the locus of I! as the 0,0,0 (X,Y,Z) coordinate of origin within our phenomenal egocentric space.

Hi Wayne,

What I had in mind is something along the following lines (I am not sure whether this is coherent):

When the object moves, all goes as you suggest. But the conscious visual content only represents a movement relative to the eyes position: the object changes position relative to here (where “here” is a point). This has to be contrasted with what happens in the case of body movement.

When the head moves, instead of having a corollary discharge that cancel or compensates the updating of the head-centered frame, as you suggest, what would happen is that the position of the object is not evaluated relative to a simple point but rather to certain area (an area that I would guess depends on the speed of the head movement). Imagine that the position of the object changes from {x, y, z} at t1 to {x’, y’, z’} at t2 due to the movement of the head. The visual system will represent that that the object has not moved (relative to here) insofar |x-x’|<delta, |y-y'|<epsilon and |z-z'|<gamma, where the values {delta, epsilon, gamma} depend on the movement of the head. They demarcate the area relative to which the content is evaluated (the “here”, which would not be a point when the body moves)

Is this understandable? Does it make any sense?

One empirical consequence of what I postulated is, I think, that we would be worst detecting the movement of objects as we also move (and the faster we move the worst). In your model one would not expect this.

Apologies for the slow reply. Will be back soon as I’ve been tied up with a conference.

Hi all–

Very excellent paper and discussion–kudos to all y’all.

My lingering worry is that the ventral stream is getting framed in too narrow a way, making it easier to establish the need for dorsal info. This is something like an a priori worry, because I haven’t had the chance to check much of the lit, beyond my standard late 90s understanding of Milner and Goodale. But is it really true that NO egocentric mapping/framing/whatever goes on in the ventral stream? My guess is another effect of M&G’s initial rhetoric is to make ventral seem too abstract and what-y. But if it’s richer in location content, the division may remain.

What prompted my posting was the following article from Neuron: “A Channel for 3D Environmental Shape in Anterior Inferotemporal Cortex” (Siavash Vaziri, Eric T. Carlson, Zhihong Wang, Charles E. Connor) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0896627314007442

It argues for a where-ish channel in ventral stream, involving what they call “environmental shape.” I’m not sure this is enough to ground stability, but it suggests to me that more might be in that stream than Wayne’s setup suggests (no doubt that’s M&Gs fault, not Wayne’s!). Maybe this is old hat or dealt with in the commentaries–sorry for a cursory read.

I agree with the basic point that the what/where division is far too sharp, but I do wonder if a conscious/nonconscious boundary of some sort might be present here? There’s a difficult causal vs. constitutive question here, as Pete points out.

Further, I would have thought that activation in neither stream is sufficient for consciousness (there seem to be unconscious cases of both, ie.). Whatever additional process is needed may recruit both dorsal and ventral information for working memory or a global workspace or a higher-order monitoring system or something. Perhaps activation in both streams causes states with certain contents to be tokened further up the line, rather than constituting consciousness content on its own. Just a thought.

Cheers,

Josh

Hi Josh:

Thanks for that. Does the ventral stream carry egocentric representations? I think this remains an open question, but I believe that as evidence currently stands, there isn’t anything equivalent to the sorts of body-centered activity that is seen in the dorsal stream. So, my claim is a hypothesis based on the current evidence. But I agree that this might be falsified later. I’m not sure about the result that you cited but will have to look at that when I have a moment.

I agree that the claim isn’t that the dorsal and ventral alone suffices for consciousness. I guess I would say something like the two suffice for a specific content of consciousness, namely determining the egocentric location of a visible object as visually experienced, but of course with the caveats that prompt your last comment. I don’t think that claim should be too controversial.

The issue at this point seems to be a shift of focus to how the two streams work together whereas before, the emphasis was on drawing sharper boundaries if only for spurring debate. M&G are very clear about this in the original preface to their book about putting things very starkly to make the functional roles of each stream sharply contrasted. I think we probably need to walk back some of the rhetorical ploys of the past decade to get a clearer view of the interactions between the two streams.

There must be a system of brain *mechanisms* that give us our egocentric representations. Even though dorsal and ventral “streams” contribute to this essential system, I wonder if thinking in terms of these streams diverts our attention from an elucidation of what a competent system of mechanisms must be able to do, and how it might be able to do what is needed. The retinoid system is my candidate system of mechanisms for realizing egocentric representations.

Thanks Arnold. I argue that given the sort of body-centered activity that is well documented in areas like LIP and VIP in the monkey dorsal stream, we have good evidence that the dorsal stream makes egocentric spatial contribution to vision. The paper then goes on to make arguments as to why we should take this contribution as important in the egocentric aspects of consciousness. I’m sorry as I’ve not had time to read your paper and due to now being behind on other matters, am not going to be able to do so before this symposium is over, so I was hoping for a more detailed exposition to help set the two models apart. I understand that you speak of a “retinoid” system, but I still don’t have a handle on what that means so am not able to contrast the two views.

Could you say more in detail? If it’s too complex to explain in a reply, then perhaps we’ll have to leave the conversation at this point, namely the possibility of two contrasting models where contrasts are to be further elucidated? Interested parties, of which I am one, can look into your publications further when time allows.

Wayne, there is no question about the fact that areas like LIP and VIP in the dorsal stream make egocentric spatial contribution to vision. What you call the “contrasting models” concerns the difference between the usual “black box” model in which an anatomical feature like the “dorsal stream” is proposed as an explanatory construct, and a model like the retinoid model in which a a detailed neuronal mechanism is proposed as an explanatory construct. It seems to me that only a theoretical model of brain *mechanisms* with a detailed structure and dynamics can predict the kinds of relevant data that will enable us to understand how the brain actually does the work of egocentric representation.

Separate sensory modalities alone cannot represent their stimuli properly bound within a coherent global brain representation around a point of spatio-temporal origin. In other words, the cortical sensory mechanisms alone cannot account for subjectivity/consciousness. What is needed is a system of neuronal mechanisms that can represent all sensory information, properly bound, in a volumetric space organized around a “point” of perspectival origin. Activation of this kind of brain mechanism seems to be required to produce subjectivity/consciousness. The neuronal structure and dynamics of what I have called the retinoid system provides a theoretical model of the kind of brain mechanism which, in recurrent feedback with all sensory mechanisms, gives us subjectivity — a coherent representation of our phenomenal world from our privileged egocentric perspective.

Thanks Arnold. That sounds like an interesting approach, and at a general level, to the extent that I’m tracking, it sounds right. My aims are more minimal in the paper, to identify an informational correlate with a phenomenal correlate which, it turns out, has some bearing on a functional characterization of the visual streams, a topic we haven’t discussed much in this exchange. I suspect that the functional division should be understood as rough and ready, a way of emphasizing functions carried out by each anatomical stream and perhaps, less than something like a “module” in its many senses that implies a stronger division. I’m against divison in this context, at least with respect to certain ways of framing the functional account of the streams.

Is there a place for informational/phenomenal correlation on your model, dynamics aside? At some level, it seems like we might be after somewhat different goals, at least in your response. There are two questions one can distinguish:

1. What is necessary, neurally speaking, for having consciousness at all, irrespective of its specific character (at what ever level you want to cut consciousness)?

2. What is necessary for consciousness having some specific character, e.g. spatial constancy?

I emphasize the latter; your response emphasizes the former, it seems (though you need not be thereby uninterested in the latter).

Thanks, Wayne. Awesome work here.

Cheers.

Hi Wayne,

You asked:

“1. What is necessary, neurally speaking, for having consciousness at all, irrespective of its specific character (at what ever level you want to cut consciousness)?

2. What is necessary for consciousness having some specific character, e.g. spatial constancy?”

1. I think my working definition of consciousness answers the question of what is necessary for a minimal level of consciousness to exist. Here it is:

*Consciousness is a transparent brain representation of the world from a privileged egocentric perspective.*

2. The spatial constancy of consciousness is realized by the fixed locus of perspectival origin (I!) within the spatiotopic neuronal structure of retinoid space. See “Modeling the World, Locating the Self, and Selective Attention; The Retinoid System” and “Where Am I? Redux”, here: https://people.umass.edu/trehub