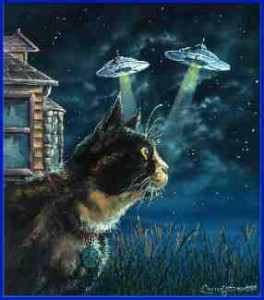

A year ago we met an alien species (Part I) that lacked subjective conscious states but were virtuoso scientists. They developed a detailed understanding of cat  brains at every level of organization, but still did not realize that cats were conscious. This was parlayed into an argument for dualism (Part II). Namely, if full knowledge of a brain doesn’t reveal subjectivity, and this is a logically necessary limitation of any purely neural approach, then this is an inductive catastrophe for the materialist. In this post I explore (and ultimately reject) the idea that phenomenal concepts provide a way out for the materialist. I suggest that a better escape for the materialist is to reject the view that knowledge of subjectivity is necessarily sealed off from neural theories.

brains at every level of organization, but still did not realize that cats were conscious. This was parlayed into an argument for dualism (Part II). Namely, if full knowledge of a brain doesn’t reveal subjectivity, and this is a logically necessary limitation of any purely neural approach, then this is an inductive catastrophe for the materialist. In this post I explore (and ultimately reject) the idea that phenomenal concepts provide a way out for the materialist. I suggest that a better escape for the materialist is to reject the view that knowledge of subjectivity is necessarily sealed off from neural theories.

The problem

In Part I, I introduced an alien species that lacked conscious experiences (and concepts about such experiences), but acquired detailed scientific knowledge of the cat brain at every level of organization. This included knowledge of complex neural states that the aliens called ‘smonscious states’ which isomorphically and intuitively mapped onto (what we would call) the cats’ conscious subjective experiences.

However, as discussed in Part II, the aliens never came to understand that the cats have subjective experiences, as such. This is not, by itself, a problem. It is justifiably a truism that conceptual differences do not imply ontological differences. When Mendel talked about genes in pea plants, he wasn’t intending to talk about complex stretches of DNA. Similarly, perhaps there is one underlying neural reality that can be accessed and conceived in two ways. Experiences can be described in neuroscientific terms that are available to outsiders that study brains, and in phenomenal terms available to those insiders whose brains instantiate the relevant properties. While there is admittedly a dichotomy of concepts, there is no dichotomy of properties or substances.

The dualists are familiar with such considerations, and their argument doesn’t merely depend on a semantic difference, but on the semantic poverty of neuroscience. That is, it seems that no amount of analysis, conjunction, or <insert your favorite semantic construction method here> applied to concepts about brain states will yield a concept about subjective experience as such. We’ll call this the semantic poverty thesis [1]. If the aliens are restricted to theorizing based only on their neuronal theory (they are), they could never in principle come to understand that cats have experiences.

There is no semantic poverty thesis for any of the standard examples of co-referring concepts from the natural sciences. For instance, it seems easy to imagine how our scientifically astute aliens could bridge the relevant conceptual domains between molecular biology and Mendelian genetics. If restricting oneself to neuronal theories permanently seals you off from knowing that subjects are conscious, then we seem to have an inductive catastrophe for the materialist, regardless of any plausibility-straining logical possibilities.

Phenomenal concepts to the rescue?

Many naturalists simply accept the semantic poverty thesis, and argue that materialism is still the best game in town. In particular, it is popular to attempt to explain semantic poverty using the phenomenal concepts strategy (PCS). This involves the hypothesis that there exists a special set of concepts that we use to directly refer to our own experiences, concepts that can initially only be acquired by those who instantiate the relevant subjective experiences. Folks have been doing phenomenology, directly describing their perceptual experiences, for centuries, independently of any scientific understanding of said experiences. We can say things like ‘That pain in my tooth has returned’ independently of any thoughts about the basis of the pain, without a jot of abstruse metaphysical knowledge.

Since our phenomenal conception of experience can be deployed without staking any claim as to the basis of such experiences, it is not surprising that people can conceive of experiences occurring independently of brains. Carruthers and Veillet (2007) write:

[W]e possess a special set of concepts for referring to our own experiences. What is said to be distinctive of such concepts is that they are conceptually isolated from any other concepts that we possess, lacking any a priori connections with non-phenomenal concepts of any type (and in particular, lacking such connections with any physical, functional, or intentional concepts). Given that phenomenal concepts are isolated, the physicalist argues, then it won’t be the least bit surprising that we can conceive of zombies and inverts, or that there should be gaps in explanation. This is because no matter how much information one is given in physical, functional, or intentional terms, it will always be possible for us intelligibly to think, “Still, all that might be true, and still this [phenomenal feel] might be absent or different.” There is no need, then, to jump to the anti-physicalist conclusion.

That is, if PCS is correct, then we should expect that people can (incorrectly) think that there could exist ghosts (agents with mental states that float about independently of brains), or philosophical zombies (physical duplicates that lack the same conscious experiences as us). But we should resist the temptation to slide into ontological dualism based on such merely conceptual exercises.

Dualist response

While interesting, the PCS doesn’t directly deflect the dualist’s concerns. For one, it explicitly affirms the dualist’s premise that the aliens will never know that the cats are conscious. But this is precisely the problem. If we are meant to take the alien’s theory as a literally true and complete account of the properties of the cat’s brain (we are), and consciousness is a property literally instantiated by the cats (it is), then the aliens’ neural theory is simply incomplete. A complete inventory of reality should explicitly mention conscious experiences, and it should be seen as a scandal for materialism that if you limit yourself to neuronal theories, you will never acquire the knowledge that subjects are conscious.

Using the PCS, the materialist squirms around shifting the discussion from consciousness to concepts about consciousness. In contrast, the dualist is on much stronger footing when it comes to explaining phenomenal experiences. She can unflinchingly focus directly on the system instantiating the relevant properties, and will not wind up in the embarrassing situation in which someone understands their dualistic theory but does not know that cats have experiences.

Note just how low the bar is set for the materialist. We aren’t asking for the aliens to know the subjective character of red, but to realize that there is some experience there, period. It seems reasonable to expect a complete theory would leave the aliens in a position analogous to Mary before she leaves her black and white jail. That is, she knows she lacks color experiences (i.e., her brain has yet to instantiate the relevant color-seeing properties), and she knows she lacks the typical cognitive reactions to having that experience (e.g., she will not recognize red when she sees it the first time). We don’t expect her (or the aliens) to acquire the experiences she is studying. This would actually go against the thesis under question, that experiences are brain states of a certain type. We would not expect our aliens to experience red any more than we expect to photosynthesize upon acquiring expertise on the topic of photosynthesis. Materialists are committed to the view that experiences are brain states, not that studying consciousness magically induces such brain states.

So the bar is set pretty low, and while logically possible as a materialist response, the phenomenal concept strategy amounts to blithely running underneath the bar [2].

Better option?

A better option for the materialist, who wants to avoid going down this road, is to attack the semantic poverty thesis. After all, nobody has given a particularly strong argument for the claim. It is typically either treated as axiomatic, or perhaps some halfhearted justification is presented. For instance, Chalmers (1995) writes:

But the structure and dynamics of physical processes yield only more structure and dynamics, so structures and functions are all we can expect these processes to explain. The facts about experience cannot be an automatic consequence of any physical account, as it is conceptually coherent that any given process could exist without experience.

It seems a mistake to allow substantive debates to be swayed based on inconclusive declarations about how two extremely complex domains relate to one another. In the next (and last) post [Part IV], I will develop a case against semantic poverty, arguing that the aliens could close the gap between brains and experiences. This will allow materialists to jump over the bar that was set above.

Notes

[1] If true, the semantic poverty thesis implies there is an explanatory gap, a ‘Hard Problem’ of explaining consciousness: if neuroscience is too conceptually impoverished to say you are having an experience, there is no way it can explain said experience (at least in the sense of ‘explains’ that Chalmers uses to underwrite the Hard Problem). I am presently leaving out the possibility that the aliens could learn about phenomenal concepts if they talked to, or studied, humans, as it seems to be a cheat.

[2] I am actually more sympathetic to the PCS than I let on here, but to save space I am moving on rather quickly to what seems a better response.

References

Carruthers, P, and Veillet, B (2007). The Phenomenal Concept Strategy. Journal of Consciousness Studies 14: 212-236.

Chalmers, D (1995) Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies 2: 200-219.

The question I would ask is whether there is any empirical test that distinguishes between consciousness and smonsciousness. It seems to me that if there is such a test, the logic here falls apart, but if there is no such test, then by Occam’s razor consciousness and smonsciousness must be treated scientifically as the same thing, regardless of all the terminological juggling.

Bill: interesting point. To answer your question: there is a perfect isomorphism between the two, and no experimental test to tell them apart.

That said, I would suggest that the razor you speak of is actually an eraser. By keeping the two notions distinct, we gain explanatory and descriptive power regarding subjective experiences.

Where the aliens talk about complex neural states representing the world, we can talk directly about the texture of our experiences of the world. The latter is not something we want to get rid of, even if it doesn’t have a place in science. To jettison the phenomenological conception of ourselves would be a tragedy, not progress.

There is a rich suite of phenomenological concepts that we can use to talk about love, taste, music, and we don’t have to get bogged down in details about how these experiences are implemented. This, I think, is the truth contained in the PCS.

That said, I think the aliens could build a bridge from brains to phenomenology, so we don’t have to choose between the two. That is, neuroscience is not as conceptually impoverished as the dualists (and many materialists) think it is. That is for Part IV, which I have written, but I will post in a week or so.

It seems to me that you’ve made this confusing by talking about cats rather than humans. If the aliens were studying humans rather than cats, and they had a complete understanding of the human brain and its relation to behavior, then presumably they would be able to replicate our talk about the texture of our experiences — because after all, talking is just one specific type of behavior. And if that’s the case, we don’t have any practical advantage at all over the aliens, as far as I can see. But maybe that’s where you are going with part 4?

Bill: a good point, and one I addressed buried at the end of note 1, where I wrote, “I am presently leaving out the possibility that the aliens could learn about phenomenal concepts if they talked to, or studied, humans, as it seems to be a cheat.”

Just to expand on that: I purposely picked cats because cats do not do phenomenology, and I wanted to make things tougher for the materialist, to close the loopholes that would let them avoid the crux of the matter. If cats are conscious, the aliens should be able to discover this fact without sneaking in phenomenological reports directly from humans.

Thanks Eric, but I can’t see any way to reconcile the following two sentences with each other:

* “There is a perfect isomorphism between [consciousness and smonsciousness], and no experimental test to tell them apart.”

* “If cats are conscious, the aliens should be able to discover this fact without sneaking in phenomenological reports directly from humans.”

It looks like you are asking for magic.

Bill: I should qualify that in my first claim I meant to suggest that there is no single empirical measurement (e.g., sticking in more electrodes, or more Tesla in the MRI) of cat brains that will differentiate smonscious from unsmonscious processes. But that doesn’t mean that, based on the theory and measurements they already have, they cannot expand their understanding of smonsciousness in new directions (like Darwin before natural selection, but during the Beagle). I am going to post the fourth post now, so I don’t keep dramatically referring to it as if it contains magic. 🙂

Thanks for the interesting post, Eric,

In your response to Bill Skaggs, You write:

“By keeping the two notions distinct, we gain explanatory and descriptive power regarding subjective experiences.”

The claim is interesting, but I feel it is not entirely clear, given that you accept physicalism. If a given phenomenal concept merely serves to pick out some property, of which we have rich and complete scientific description, then it seems that the phenomenal concept does *not* provide us with any additional explanatory or descriptive power (other than in the trivial sense of providing us with a new label, or name, for the property).

Perhaps what you say next is meant to shed light on this issue. You write:

“There is a rich suite of phenomenological concepts that we can use to talk about love, taste, music, and we don’t have to get bogged down in details about how these experiences are implemented”

This is correct. Is this what you mean by the claim that phenomenal concepts enhance our explanatory and descriptive powers? Compare this to other natural kind concepts. We can talk about coffee without worrying about the details of the molecular structure of coffee. Does this mean that the concept “coffee” enhances our explanatory and descriptive powers, in your sense? If the answer is “yes”, does this mean (given your parallel argument about experiences) that the physical (chemical) theory of coffee is “incomplete”, thereby creating a scandal for this theory? This sounds wrong. If the answer is “no”, then I think you should clarify in what sense exactly phenomenal concepts enhance our explanatory and descriptive powers.

Thanks Assaf tough question…literally about to fall asleep, hope I don’t become too incoherent here!

You wrote:

>>> We can talk about coffee without worrying about the details of the molecular structure of coffee. Does this mean that the concept “coffee” enhances our explanatory and descriptive powers, in your sense? If the answer is “yes”, does this mean (given your parallel argument about experiences) that the physical (chemical) theory of coffee is “incomplete”, thereby creating a scandal for this theory? This sounds wrong. If the answer is “no”, then I think you should clarify in what sense exactly phenomenal concepts enhance our explanatory and descriptive powers.

Great example. I see two main issues here.

First, what generates the scandal for consciousness, and makes it unique, is the semantic poverty thesis. There is no intuitive semantic poverty or explanatory gap between molecular and molar descriptions of coffee. Our aliens might not have the concept of coffee, but this would be a contingent fact, not a necessity.

Second, my resistance to simply getting rid of phenomenal concepts, given that they map perfectly onto the alien neural theory, was based on a few things. Not the metaphysics, obviously, for reasons you point out, but for more practical reasons.

One, people truly are subjects that have experiences. Why would we want to get rid of this notion?

Similarly, while we *could* get rid of the notion of ‘coffee’ and replace it by some molecular complex description, in practice (for reasons you nicely stated) this would be a mistake. Similar for experience-talk.

Finally, equivalent extension doesn’t mean equivalent meaning or equivalence of psychological consequences within a mental economy. Thinking phenomenologically is likely important for moral reasoning, empathy, and also practical communication.

An explanation like ‘I went to the dentist because of that damned pain in my mouth’ just seems useful, probably evokes a direct empathic response. As an explanation of why you went to the dentist, I have trouble seeing why we would want to eliminate it. This isn’t an argument as much as a request for a good reason to change course.

That said, I cannot argue against the possibility of a Churchlandian future where we end up using neuronal terminology, and it serves dual purposes, and people divine from the context whether someone is speaking phenomenologically, about their own experiences, or neuroscientifically, about experiences scientifically studied in the lab and examined by a different route.

My hunch is such a shift would, in practice, *decrease* the expressive power of the English language (this seems like basic combinatorics, no? :)), not to mention that it comes off as wanting to replace a color palette with grey-scale. I guess I have an aesthetic attachment to phenomenology.

I hope this all makes half-sense, must roll over and sleep now….

Thanks for the helpful clarifications, Eric.

I hope this message does not somehow beeps in your smartphone, thereby waking you up (it’s noon here).

It will be great if you could clarify the matter more. Do you think that the semantic poverty thesis is scandalous *by itself*, or only when combined with your other thesis (call it the phenomenal significance thesis) that phenomenal concepts afford greater explanatory and descriptive powers? If the former, then something is strange dialectically. For, PCS entails the semantic poverty thesis, and no one (in the literature) claims that PCS is scandalous . Surely, many philosophers criticize PCS, but they do so by pointing to some specific problem with it, not by simply rejecting it as scandalous.

If you think that the semantic poverty thesis needs to join forces with the phenomenal significance thesis, in order to generate the scandal, then I think you should clarify how exactly the two theses combined achieve this.

In light of Skaggs’s initial comment and your reply to it, I have the impression that you accept the latter option, because of something like the following reason: if phenomenal concepts do not afford greater explanatory and descriptive power, then we have good reason to simply get rid of them, and if we get rid of them, then semantic poverty is no scandal. For, not being able to yield a concept (i.e., a phenomenal concept) that we do not need anyway, is not a bad sort of poverty. So, in order for the poverty to be scandalous, it is crucial that phenomenal concepts would afford some significant (even if merely practical) benefit.

Is this your line of thought?

Assaf: I think semantic poverty is controversial, and is all that is needed to keep the aliens in the dark.

The many practical reasons I think phenomenal concepts are helpful I already largely addressed. This included my admission that I cannot prove that they could not be reduced/replaced in some Churchlandian future, even among ordinary folks. This is more a pragmatic/romantic point than substantive point, perhaps.

Thanks for this very interesting and thought-provoking piece! I am troubled by some of the counterfactual knobs you are twisting here: “an alien species that lacked conscious experiences, but acquired detailed scientific knowledge” makes no sense to me: they have no subjective experiences but they have knowledge? What would it mean to say that they are “proposition crunchers”? Can you entertain a thought without actually having a thought (if this sounds paradoxical, it reflects my bafflement at how to understand your premise)? Once you accept the possibility of thinking (of any kind) without subjectivity, haven’t you completely conceded any point the materialist would like to make? As Chalmers argues, any single process can occur without consciousness, so we just should become eliminativists or identity theorists and we would have saved the materialist framework! But, as you claim, “A complete inventory of reality should explicitly mention conscious experiences”, and perhaps platonic entities (such as propositions in themselves) as well. It is not that the aliens doen’t have any access to these (they do have access to some of their causes and some of their effects), they just lack the capacity to experience them as what they are from the first-person point of view. Indeed, “Folks have been doing phenomenology, directly describing their perceptual experiences, for centuries, independently of any scientific understanding of said experiences.”, but here you are conflating folk-psychology and the systematic / scientific study of experience from the first-person perspective. We can have a science of consciousness based on (inter)subjective experience (as Brentano and Husserl would certainly argue), so it is not obvious that materialism is the best game in town, it certainly is not the only one. Indeed, it only gets off the ground once you accept the (intelligibility) of the first premise: the possibility of knowledge without a knower.

Carlo you make an interesting point. First, I should mention that I discussed the very real ‘incoherence’ concern explicitly a couple of times in Part I. In the post I wrote:

” Note I realize this may ultimately be an incoherent scenario, but let’s go with it to examine the implications, if any, for the materialist. After all, if materialism can escape unscathed from a story custom-made to favor antimaterialism, that will bode poorly for many weaker species of antimaterialist arguments. ”

And in the comments I wrote:

“Arnold in general those that really can’t enter the counterfactual scenario I’ve painted without feelings of incredulity, I think they should think of it not as unconscious alien scientists, but simply a community of humans who are radical behaviorists by nature, who do not have the concept of consciousness, who decide to study brains.”

But you have a new objection, that this actually helps the materialist. You wrote:

“Once you accept the possibility of thinking (of any kind) without subjectivity, haven’t you completely conceded any point the materialist would like to make?”

I am assuming that we can distinguish propositional cognition from nonpropositional conscious experience, and that the former can be unconscious. We seem to have unconscious thoughts and cognitions (but not unconscious conscious experiences), so it isn’t *that* far fetched to imagine a species for which all their thoughts unconscious. This should also explain my use of the term ‘proposition crunchers.’

Obviously, if you are right, then the scenario won’t work, but I think that works in the materialist’s favor (this scenario is very hard for the materialist to deal with, and if by definition to think is to be conscious, then they would never find themselves in this quandary so this reductio against materialism will never come up! My life as a materialist would be much easier without this reductio.).

Note to explain more how I have tweaked the knobs to make things *very* hard for the materialist. Unlike Mary scenarios, they have no conception of experience to draw on. They study cats, so they cannot cheat and simply parasitize the semantics of phenomenal concepts from humans.

Thank you for the clarification! “I am assuming that we can distinguish propositional cognition from nonpropositional conscious experience, and that the former can be unconscious.” So the aliens have only unconscious cognition, but this implies what I claimed: you are stipulating the possibility of propositional attitudes (“knowing that …”) without a subject to have them. These aliens aren’t behaviourists, they are piles of data, collections of content without any mental acts that they are the contents of. Now of course it is possible to do some “brain reading” and establish correlations between stimuli and effects on the brain, and the materialist would claim to be done once he has a complete list of those. What he is missing, though, are the intentional acts directed at the contents and propositions. The aliens would lack any possibility of reflecting on their subjective acts (since they don’t have them) and hence have no way of knowing that they know (or doubting, etc.). In what sense would they even be capable of theorizing? Once you allow all these things to happen without any concsciousness required, you’ve effectively buried the bar in the ground. The aliens can explain away subjectivity as a superfluous epiphenomenon, a side product of the brain, that actually does all the work.

Carlo:j I think you are bringing up interesting questions that go way beyond the localized topic I focused on. The essential question is whether you could, in principle, come to know that subjective experience exists (if natural-scientific knowledge/methods are your basis). This conceptual exercise doesn’t really require these kooky aliens, but I simply used them to make the point more vivid, to make it tougher for the materialist.

Hi Eric, you say you are more sympathetic to PCS than your post lets on so maybe this is besides the point but I don’t see what your objection to PCS is supposed to be or why you think that the bar for the materialist is lower if the aliens just need to come to the conclusion that cats have experience of any kind.

The concept of ‘experience’ here is ‘there being something that it is like for one’ so your aliens will have to come to the conclusion that there is something that it is like for cats to represent the world, but since there is nothing that it is like for the aliens how will they ever be able to get that concept? They will end up explaining all of the cat’s behavior in neural terms without ever using that concept so why would they need to add anything? This is the crucial difference between your aliens and Mary. May has some behavior that she can’t explain and that is the behavior of people who talk about phenomenology (plus her own conscious experience in other modalities). So she has a third-person concept of phenomenal consciousness (and a first-person concept of what it is like to hear, see in general, etc) and then when she sees red she gets the specific first-person one (that is why she is thought to exclaim ‘oh, so THAT’S what it is like to see red!’ she already knows there is something that it is like but just doesn’t know what it is like). The aliens don’t have that. All they have is the behavior of the cat, and they fully understand that without concepts like ‘phenomenal consciousness’ and ‘what it is like’. That doesn’t seem like a low bar at all. It seems as high as the original bar.

Thanks Richard. Your comments are indicated with ‘>>>’

>>I don’t see what your objection to PCS is supposed to be

PCS affirms an important premise in the dualist argument, the semantic poverty thesis. They don’t contest the premise, but actually justify it. That, essentially, is my problem (that, and switching to talking about concepts about systems instantiating experiences, rather than being able to directly focus on the system and find out it is conscious).

Note I gave the qualifier about my sympathy with PCS because I know there are interesting arguments we could have. I’d be happy to be shown wrong: I came into this hoping PCS would save the day, frankly, but I just don’t buy it–I tried hard to buy it, but it just kept coming off as deflecting the issues. That’s why it has taken me a year to respond to myself.

So rather than enter the PCS debates in more detail, I just pointed out that PCS actually supports the key premise of the dualist’s argument, claim that this is actually evidence against materialism, and suggest that if the materialist can plausibly block semantic poverty, we can avoid this entire avenue.

>>>or why you think that the bar for the materialist is lower if the aliens just need to come to the conclusion that cats have experience of any kind.

Good point. Root intuition I was using for that claim: it is an easier hurdle to know that X has mass, than to know that X has mass 15 kg.

Also, if it doesn’t become more clear why I think I have set the bar low in my next post, then you should let me know. Note that not much really rides on this, frankly, and I admittedly was going on intuition built from Post IV, which I haven’t put up yet.

>>>The concept of ‘experience’ here is ‘there being something that it is like for one’ so your aliens will have to come to the conclusion that there is something that it is like for cats to represent the world, but since there is nothing that it is like for the aliens how will they ever be able to get that concept?

That is precisely the problem: they don’t even realize they are in the dark wrt experience. It’s *that* bad.

You are confirming the semantic poverty thesis (‘how would the aliens ever be able to get to that concept’ is something I will address in post iv).

>>>They will end up explaining all of the cat’s behavior in neural terms without ever using that concept so why would they need to add anything? This is the crucial difference between your aliens and Mary. Mary has some behavior that she can’t explain and that is the behavior of people who talk about phenomenology (plus her own conscious experience in other modalities).

Before going down the Mary road, let me just note that regardless of how one evaluates the Mary situation, it seems pretty clear that if the aliens reach her level of knowledge, that would be a huge achievement. She knows that other people have color-experiencing brain states, and that she lacks such experiences/brain states herself, etc..

The aliens are in a much worse position: they have no such conceptual resources: they don’t even know the cats are conscious. If the semantic poverty thesis is true, then they never can.

Obviously, PCS was erected specifically to deal with such gaps. I used the alien scenario to lay down the problem in stark terms, to highlight just how bad things are for the materialist who accepts semantic poverty.

I have always thought of the aliens as Mary on bath salts, or Mary turned to 11. Probably not qualitatively different, but different enough to make me reconsider things without the usual loopholes.