In 1890 William James introduced the metaphor of the “stream of consciousness” into Western psychology: “Consciousness… is nothing jointed; it flows. A ‘river’ or ‘stream’ are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life.”

Over a thousand years before, the same image figured prominently in the Buddhist philosophical tradition known as the Abhidharma. There the Buddha is portrayed as saying: “The river never stops: there is no moment, no minute, no hour when the river stops: in the same way, the flux of thought” (quoted in Louis de la Vallée Poussin, “Notes sur le moment ou ksnana des bouddhistes”).

For both James and the Abhidharma, mental states don’t arise in isolation from each other; rather, each state arises in dependence on preceding states and gives rise to succeeding ones, thus forming a mental stream or continuum. However, James and the Abhidharma have different views about the nature of the mental stream.

According to James, although the mental stream is always changing, we experience these changes as smooth and continuous, even across gaps or breaks. The gaps and changes in quality that we do feel or notice—for example, when we wake up from a deep sleep—don’t undermine the feeling that our consciousness is continuous and whole. And the gaps and changes in quality that we don’t notice aren’t felt as interruptions because we’re not aware of them.

The Abhidharma philosophers agree that the mental stream is always changing, but they argue that it appears to flow continuously only to the untrained observer. A deeper examination indicates that the stream of consciousness is made up of discontinuous and discrete moments of awareness. Part of this deeper examination comes from philosophical analysis; part of it comes from meditation practice (the exact relationship between the two being a matter of debate among Buddhist scholars).

If the classical Abhidharma philosophers were alive today, they might wonder whether experimental psychology and neuroscience would have anything to say about these matters. Is there any scientific evidence for measurable discrete moments of experience in the “stream” of consciousness?

In 1979, when I was sixteen, I took part in an experiment that neuroscientist Francisco Varela devised to investigate whether perception is continuous or discrete. I’d never been to a neuroscience lab, and the prospect of seeing my own brain waves was enticing. Francisco and I set off from Sixth Avenue and 20th Street, where we lived at the Lindisfarne Association, to the New York University Brain Research Laboratories at 550 First Avenue. I sat in a dark room with electrodes fixed to my scalp and watched two small lights flash on and off. My task was to say whether the lights were simultaneous or sequential, or whether there was one light moving from left to right.

It’s well known in experimental psychology that there is a certain minimal window of time within which two successive events will be consistently perceived as happening at the same time. For example, if you’re shown two successive lights with less than about 100 milliseconds between them, you’ll see the lights as simultaneous. If the interval is slightly increased, you’ll see one light in rapid motion. If the interval is further increased, you’ll see the lights as sequential. These phenomena of “apparent simultaneity” and “apparent motion” have sometimes been interpreted as supporting the idea of a discrete “perceptual frame,” according to which stimuli are grouped together and experienced as one event when they fall within a period of approximately 100 milliseconds.

If perception is discrete—if it unfolds as a succession of perceptual frames with a gap between each frame and the next one—then we can make the following prediction: whether two distinct events will be judged as simultaneous or sequential depends not just on the time interval between them but also on the relation between the timing of each event and the way perception falls into discrete and successive frames, that is, the ongoing process of perceptual framing. In particular, two events with the same time interval between them can be perceived as simultaneous on one occasion and as sequential on another occasion, depending on their temporal relationship to perceptual framing: if they fall within the same perceptual frame, they’re experienced as simultaneous, but if they fall in different perceptual frames, they’re experienced as sequential. In short, what you perceive as one event happening “now” depends not just on the objective time of things but on how you perceptually frame them.

It was precisely this idea that Francisco wanted to test. Already in his early years as a young scientist, Francisco’s research was strongly motivated by a vision of the brain as a self-organizing system with its own complex internal rhythms. (Although popular today, this vision was a small minority view in the 1970s, when most scientists thought of the brain as a sequential-processing computer.) These rhythms, he believed, bring forth meaningful moments of perception in a fluctuating and periodic way. Francisco was also intrigued by the parallels between the Abhidharma notion of discrete “mind moments” and the neuroscience view of discrete perceptual frames created by the brain’s self-generated rhythms. A month or so before my visit to the NYU Brain Research Lab, Francisco and I had talked about the Buddhist idea of “mind moments” and the gaps between them as we walked to the old Paragon Book Gallery on East 38th Street, where he bought a hard-to-find copy of Louis de la Vallée Poussin’s classic French translation of Vasubandhu’s Treasury of Abhidharma. It was only after the experiment that Francisco told me what he really wanted to do was measure a “mind moment.”

In the experiment, Francisco recorded the brain’s ongoing EEG alpha rhythm and used it to trigger when the two lights flashed on and off. The hypothesis was that seeing the lights as either simultaneous or in apparent motion would depend on when they occurred in relation to the phase of the ongoing alpha rhythm. Like a surfer catching a wave, if the lights arrived at a certain point of the repeating alpha cycle, they would be seen as simultaneous, but if they missed the wave, they’d be seen as in apparent motion. In other words, presenting two flashes of light always with the same time interval between them, but at different phases of the alpha rhythm, would result in noticeably different perceptions.

The results supported the hypothesis: when the lights were presented at the positive peak of the alpha rhythm, they were almost always seen as in apparent motion, but when they were presented at the negative peak (the opposite phase), they were seen as simultaneous. In the published study, a figure showed my visual performance along with that of two other participants (see the bar labeled “ET” in the figure below from the original paper). At an interval of 47 milliseconds between flashes, my discrimination between simultaneity and apparent motion was at a chance level, but there was a change in the probability of my perceiving the lights as simultaneous when they were presented at either the positive or the negative peak of my ongoing alpha rhythm.

Unfortunately, these promising results have proved difficult to replicate, both by Francisco in a follow-up study and by other scientists today. Nevertheless, the experiment is widely cited as precisely the kind of experiment that would be needed to demonstrate definitively the discrete nature of perception; furthermore, new and more sophisticated studies are extending and deepening this line of research into the relationship between electrical brain rhythms and the pulsing character of perceptual awareness. For example, recent experiments show that whether a visual stimulus is consciously detected or not depends on when it arrives in relation to the phases of the brain’s ongoing alpha (8–12 Hz) and theta (5–7 Hz) rhythms (see also this study). You’re more likely to miss the stimulus when it occurs during the trough of an alpha wave; as the alpha wave crests, you’re more likely to detect it.

The moral of these new studies isn’t that perception is strictly discrete, but rather that it’s rhythmic; it happens through successive rhythmic pulses (an idea James also proposed), instead of as one continuous flow. Like a miniature version of the wake-sleep cycle, neural systems alternate from moment to moment between phases of optimal excitability, when they’re most “awake” and responsive to incoming stimuli, and phases of strong inhibition, when they’re “asleep” and least responsive. Moments of perception correspond to excitatory or “up” phases; moments of nonperception to inhibitory or “down” phases. A gap occurs between each “up” or “awake” moment of perception and the next one, so that what seems to be a continuous stream of consciousness may actually be composed of rhythmic pulses of awareness.

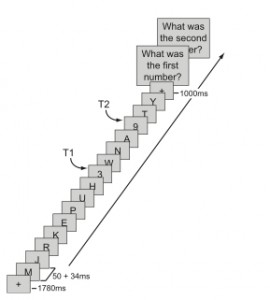

These ideas are needed to interpret the significance of some recent studies on the neural and behavioral effects of “mindfulness” meditation practice. In the well-studied cognitive psychology task known as the “attentional blink,” participants need to identify two visual targets (T1 and T2 in the figure below) presented within less than 500 milliseconds of each other in a rapid sequence of other visual stimuli.

Participants usually detect the first target but often miss the second one. It’s as if their attention blinks after they notice the first target, and the second one goes by in that instant. Neuroscientists Heleen Slagter, Antoine Lutz, and Richard Davidson investigated whether meditation practitioners would show improved performance on the “attentional blink” task after a three-month intensive retreat in Theravāda Buddhist Vipassanā or “insight” meditation. This type of mindfulness meditation cultivates both focused attention, whereby you learn to sustain your awareness on a given object, such as the sensations of the breath, and open awareness, whereby you learn to be open and attentive to whatever arises in experience from moment to moment. The scientists compared the performance of the practitioners on the attentional blink task before and after the retreat, and they also compared the performance of the practitioners with that of a control group of novices who were interested in meditation, took a one-hour Vipassanā meditation class, and were asked to practice for twenty minutes each day for a week before the experiment. After the three-month retreat, the attentional blink of the practitioners was significantly reduced, that is, the practitioners showed significantly improved detection of the second target (compared to the novice group, who also showed improvement). This improvement was also correlated in the practitioners (but not in the novices) with EEG measures showing more efficient brain responses to the first target. Furthermore, the individuals who showed the largest decrease over time in the neural activity they required to detect the first target also showed the greatest improvement in detecting the second target. Thus, a more efficient neural response to the first target seems to facilitate detecting the second one.

But there’s more. It’s well known that electrical brain rhythms in the theta frequency range (5–7 Hz) shape the rhythmic pulses of perception and attentional sampling. Slagter, Lutz, and Davidson found that intensive Vipassanā meditation practice affected these theta rhythms in ways that were linked to improved performance on the attentional blink task.

First, for both the meditation practitioners and the novices, the neural oscillations in the theta frequency range “phase-locked” to the targets when the targets were consciously perceived. If you think of the incoming stimuli and the ongoing brain activity as making up a partner dance, then the brain stays in step with its stimulus partners by matching its activity at a certain frequency and phase to their arrival. The scientists determined that whenever the targets were consciously seen, the brain had stayed in step with them by matching the phase of its theta oscillations to their occurrence.

Second, the scientists found that in the practitioners, but not in the novices, the theta phase-locking to the second target increased following intensive meditation. The brain got better at staying in step with the second target. More precisely, there was a reduction in the variability of theta phase-locking from trial to trial, which is to say that the brain’s matching of its theta waves to the second target became more precise and consistent. Furthermore, the individuals who showed the largest decrease in the neural processes required to detect the first target also showed the greatest increase in theta phase-locking to the second target. In this way, more efficient neural responses to the first target were linked to greater neural attunement to the second target. That is, individuals who required fewer resources to stay in step with the first target were also better at staying in step with the second one.

These studies using the attentional blink task indicate that intensive Theravāda Vipassanā meditation improves attention and affects brain processes related to attention. In recent years, other studies using other tasks and a wide range of meditation styles have shown that mindfulness meditation improves perceptual sensitivity and strengthens the abilities to sustain attention on a chosen object and to remain open to the entire field of awareness from moment to moment. One route by which these changes may happen is that Vipassanā meditation may fine-tune the theta oscillations that shape the stream of sensory events into rhythmic pulses of conscious perception.

So is perceptual consciousness a “stream”? Yes, in the sense that it seems to flow, but no, if “flow” means “uniformly and continuously.” Instead, the flow is rhythmic, with variable dynamic pulses.

You might object, however, that if Vipassanā meditation changes experience and how the brain operates, then we have no right to assume that ordinary, premeditative consciousness is not uniform. Maybe premeditative consciousness is uniform and Vipassanā meditation changes it. Given this possibility, it’s unwarranted to project onto premeditative experience how experience seems after meditative training.

This objection is important. As a general policy, we must avoid the fallacy of projecting qualities from later trained experience onto earlier untrained experience. In the present case, however, we have independent data from psychology and neuroscience that ordinary perception and attention exhibit rhythmic pulses, at least in certain respects or under certain conditions. We also have data about the electrical brain rhythms linked to these pulses. Given these findings, as well as the findings from the Vipassanā meditation studies on how meditation affects the same cognitive functions and electrical brain rhythms, it seems legitimate to conclude that mindfulness meditation can reveal and sensitive you to rhythmic and pulsing aspects of awareness that you may ordinarily overlook. So both James and the Abhidharma philosophers were right.

Wonderful piece. I’m a big fan of Mind in Life and it’s exciting to have you here, Evan.

Flicker fusion is dear to my heart, primarily because I think it exemplifies a way to thoroughly naturalize the first person. Your thesis is that consciousness is actually discrete, or at least rhythmic, but only seems to stream because of neglect. The thesis, in other words, is that an apparently positive (and deeply perplexing) property of ‘consciousness,’ far from having neural correlates, is actually a function of metacognitive neglect. My question is simply, To what degree does this generalize? Given your phenomenological commitments, I think this question is pretty much *the* question you need to answer (I know Zahavi punted on it when I posed it to him here several months back). If something apparently so basic as the stream of consciousness could be a positive phenomenological artifact of neglect, then why not transcendental subjectivity? The now?

(The more interesting question, the more productive one, I think anyway, is, To what degree can we see other perplexing properties of consciousness as artifacts of metacognitive neglect?)

Cognitive neuroscience is showing that metacognition is modular, that is, both fractionate and specialized—bounded like cognition more generally, only far more ‘low res.’ And this makes sense, given that no brain could possibly track itself in any high dimensional sense: we should expect metacognition to see only what solutions to various, ancestral problem ecologies required, and to neglect everything else. So the idea is that we judge consciousness ‘stream-like’ for essentially the same reason that Aristotle judged celestial bodies ‘pure’: we mistake radically limited information for sufficient information (suffer a version of what Kahneman calls WYSIATI) and draw our ontological conclusions accordingly.

Flicker fusion generalizes. In the absence of information indicating differences, we generally intuit identities, continuities (I would love for some researcher to delve into this). Do you have any principled way of sorting those phenomenological staples you do accept (like transcendental subjectivity) from those you don’t (like stream of consciousness)? After all, it could be the case that ‘consciousness’ only appears to be a ‘transcendental condition’ simply because philosophical reflection (deliberative metacognition), lacking any access to information regarding its empirical contingencies (and more importantly, lacking any information regarding this lack) mistakes a shortfall for a positive ontological feature of consciousness itself, generating a profound sense that it somehow mysteriously lies outside the empirical realm.

This view certainly has simplicity on its side.

Thanks for these comments, Scott.

I don’t think there’s a general answer to the question of how many of the apparent features of consciousness can actually be explained as a function of metacognitive neglect. The answers would have to be case by case. I also don’t think that all metacognition is a matter of belief (cognitive states with propositional content to which one implicitly assents), as some would hold. So we’d have to analyze “metacognition” too.

The issues about the transcendental strike me as occurring at a different level of analysis or in a different argumentative register. So they wouldn’t be answerable for me on the basis of empirical considerations about metacognitive neglect. At the same time, they require a different kind of argumentative support, something that goes far beyond what I was doing in this post. I give some of those reasons in Mind in Life, and in Waking, Dreaming. Being, too. I’m not sure whether I’ll get into those considerations in these posts, but we’ll see how things go.

“I don’t think there’s a general answer to the question of how many of the apparent features of consciousness can actually be explained as a function of metacognitive neglect. The answers would have to be case by case.”

I agree with this entirely: the question is whether you agree that this casts doubt on the reliability of phenomenology. If we could be so wrong about the ‘stream’ *despite the vividness of our phenomenological intuitions* then what about ‘time-consciousness,’ say?

Once the question is raised, there’s a large number of empirical findings that suggest we should expect such ‘neglect effects’ to be both pervasive and profound. The definition of metacognition you adopt really doesn’t matter, so long as you accept that it is bounded, an ecological artifact (and what else would it be?). If it’s bounded, then it’s heuristic. If it’s heuristic, then it neglects.

Neglect is always an issue. The question is whether that neglect is pernicious, whether it leads us down the garden path. When we’re using our metacognitive capacities in practical contexts (or as Gigerenzer would call them, ‘adaptive problem ecologies’), we can confidently say, No. But when we use them in novel ways, we have no such ancestral guarantee–the actual problem-solving record is all we have to go on. Given the intractable nature of phenomenological debates, it seems pretty clear that something is amiss, wouldn’t you agree?

Phenomenology is not based exclusively on first-person metacognition; it’s also based on conceptual/theoretical analysis, intersubjective methods of eliciting careful descriptive reports about experience, and methods for refining first-person attention and awareness. All of these things taken together are precisely the kinds of methods that enable us to get beyond certain entrenched forms of metacognitive neglect. If you read works on contemporary phenomenology, especially neurophenomenology, this is the view you’ll find, so it seems to me you are arguing against a phenomenological straw man. In any case, nothing in what we’ve been discussing casts any kind of global doubt on the reliability of phenomenology.

Notice also that the questions about continuousness versus discreteness that I consider in my post are not decided by rejecting phenomenology, but by using it carefully and properly in tandem with experimental science. This is the basic approach of neurophenomenology.

The reason I raise the issue of the definition of metacognition is that it isn’t one process, but consists of many processes, including meta-awareness, which I believe has its own distinctive phenomenology. So analyzing metacognition is not going to take us away from phenomenology.

I also don’t see phenomenological debates as intractable. It seems to me that careful consideration of phenomenological investigations, Western and Asian, converges on a number of shared points, though of course there are interesting differences too. But that’s the case in cognitive science too.

To be clear, I think experiential reporting is central to the process: I just think we need a more nuanced understanding as to the kinds of confounds that reporting is liable to suffer. I’m sure we agree on this much. Where we differ is in our appraisal of neglect as a potential confound. I think the role of neglect, when finally appreciated, will moot the bulk of existing phenomenological observation. I think we’ll come to realize that what you say about the ‘stream’ applies across the board.

“Phenomenology is not based exclusively on first-person metacognition; it’s also based on conceptual/theoretical analysis, intersubjective methods of eliciting careful descriptive reports about experience, and methods for refining first-person attention and awareness. All of these things taken together are precisely the kinds of methods that enable us to get beyond certain entrenched forms of metacognitive neglect.”

This was the hope of Introspectionism, as well. The problem with neglect, however, is that it’s, well, neglect. Neglect means thinking you have everything you need to solve some kind of problem when in fact you don’t.

In Husserlian phenomenology, the whole problem of neglect is papered over with ‘horizons’–which is to say, neglected. Are you saying that neglect is a prominent theme in neurophenomenology? If so, could you direct me to the material? I certainly haven’t encountered it.

“I also don’t see phenomenological debates as intractable. It seems to me that careful consideration of phenomenological investigations, Western and Asian, converges on a number of shared points, though of course there are interesting differences too. But that’s the case in cognitive science too. ”

And as I’m sure you agree, the primary *problem* with cognitive science is that there’s too damn many ‘interesting differences’–too much room for philosophers! Zahavi makes the same appeal to intersubjective convergences as you do. But as Wimsatt points out, heuristic short-circuits are generally systematic in nature: if metacognition is bounded, a collection of (blindly applied) special purpose tools, then, so long as we misapply them in *systematic ways,* we will run afoul the same kinds of errors–such as thinking consciousness possesses the property of a ‘stream.’ If you think about it, there’s precious few phenomenological claims that enjoy more consensus!

A heuristic neglect account is entirely consistent with the consensus you find in phenomenology. In fact, heuristic neglect does a good job explaining why phenomenology exhibits the *specific kind of consensus* it does: it explains the systematicity of apparent ‘insights,’ while also explaining their scientific infertility, without appealing to anything more than the limited metacognitive capacities we actually have.

Just out of curiosity, what would it take to make a neglect account of phenomenology plausible for you? You agree that neglect produces the illusion of positive properties (in the case of the stream, at least). I’m pretty sure you agree that the posits of phenomenology (and common sense psychology more generally) resist natural explanation primarily because of their strange properties. I’m certain you agree with the picture of a fractionate, specialized metacognition emerging out of cognitive neuroscience…

What precisely do you find objectionable? If you feel the tug of the argument at all, check out: https://rsbakker.wordpress.com/2015/02/07/introspection-explained/

“The issues about the transcendental strike me as occurring at a different level of analysis or in a different argumentative register. So they wouldn’t be answerable for me on the basis of empirical considerations about metacognitive neglect.”

So if a researcher were to publish findings on the statistical correlation between certain kinds of lesions and the tendency to advert to certain kinds of transcendental rationales, this would be irrelevant? Perhaps you have that lesion.

Transcendental rationales all rely on determinations of experience: this was basically Fichte’s inadvertent lesson. Reinterpret experience, you get different ‘transcendental deductions.’ The degree to which transcendental rationales rely on interpretations of experience is the degree to which they depend on our ability to interpret our experiences–that is, our metacognitive capacities.

I didn’t say empirical considerations were irrelevant to transcendental considerations; I said that the latter can’t be entirely decided on the basis of the former. The transcendental is already at work in our understanding of what it is for something to be empirically relevant to a given question, so one doesn’t get away from the transcendental by pointing to the empirical.

“The transcendental is already at work in our understanding of what it is for something to be empirically relevant to a given question, so one doesn’t get away from the transcendental by pointing to the empirical. ”

Or is this just the way it seems upon reflection? Is it simply a coincidence that our brains have no way of sourcing their own operations, and that transcendental posits act as sourceless (that is, nonempirical) sources of functional constraint? If there is a connection, it would certainly explain a number of very curious things about the ‘transcendental’ (and do so, once again, on the ontological cheap).

This is a very different kind of neurophenomenology I’m proposing, a ‘critical neurophenomenology,’ you could say, one *beginning* with a consideration of our metacognitive capacities, and what it means to exapt those capacities to do philosophical work .

Thanks for these detailed comments, Scott. I haven’t had a chance to read your blog post on introspection yet, so my comments here don’t take into account what you say there. I’ll try to read it soon. Sorry also for the length of this reply, but you raise a bunch of points in your comments above.

“I think the role of neglect, when finally appreciated, will moot the bulk of existing phenomenological observation. I think we’ll come to realize that what you say about the ‘stream’ applies across the board.”

I’m not sure what you mean by “the bulk of existing phenomenological observation.” If that’s meant to cover the numerous detailed analyses of lived experience in phenomenological psychology and phenomenological psychiatry, phenomenological analyses of the life world and social relations, as well as transcendental phenomenological analyses, including all the ways this work has inspired phenomenological cognitive science and neurophenomenology, then I don’t see analyses of neglect as likely to make this moot. If you also mean phenomenological analyses of consciousness informed by contemplative experience and practice, as we see in Indo-Tibetan philosophy, I would say the same thing. If you mean everyday “folk psychological” assumptions and beliefs about experience, especially about its underlying causes, then much of this may be made moot, but not just by cognitive science but also by careful phenomenology.

Regarding the “stream” idea, I don’t think it’s right to say that consciousness being streamlike is a complete illusion; rather, I think the task is to characterize precisely its streamlike character. “Stream,” after all, is a metaphor, so the question is how to understand the metaphor. I don’t argue in my post that there is no stream; I say that what the “stream” metaphor describes is something that’s pulsing and rhythmic. Whether it’s strictly discrete rather than continuous remains an open and undecided empirical question. So I don’t think we’re in a position to say that it’s an error to suppose that consciousness possesses the property of being a stream. (There are also vehicle/content issues to be cautious about: it could be that the vehicles of consciousness are discrete, while the contents are continuous and streamlike.)

“This was the hope of Introspectionism, as well. The problem with neglect, however, is that it’s, well, neglect. Neglect means thinking you have everything you need to solve some kind of problem when in fact you don’t.”

In my view, the received view of why Introspectionism failed is inaccurate and biased. It wasn’t so much that different labs disagreed on basic findings, as that they disagreed on how to interpret them theoretically. Also, as William James, who advocated introspection, argued, Introspectionism used a distortive and artificial form of introspection premised on an atomistic theoretical view of the mind. The moral of the problems of Introspectionism is not to do away with phenomenology but to do phenomenology better.

Also, in my view, phenomenology isn’t enough on its own; it needs to be informed by while also guiding experimental research. The two are reciprocally constraining. Phenomenological cognitive science is a progressive research program, not one based on thinking we already have everything we need.

“In Husserlian phenomenology, the whole problem of neglect is papered over with ‘horizons’–which is to say, neglected. Are you saying that neglect is a prominent theme in neurophenomenology? If so, could you direct me to the material? I certainly haven’t encountered it.”

I don’t see the concept of “horizon” as papering over neglect. I see it as applying precisely to those aspects of experience that are indeterminate and open, which condition the meaning of what seems determinate at any given moment. Indeed, I think it’s likely that a proper explication of the concept of neglect, as it pertains to consciousness, will require something like the concept of horizons. Neglect is essentially an attentional phenomenon, and a proper characterization of attentional phenomena in relation to consciousness needs the concept of horizon.

As for neurophenomenology, for a discussion of attentional biases and how phenomenology works with them concretely, see the papers by Claire Petitmengin and colleagues ( https://clairepetitmengin.fr/articles.html )

You refer to the “scientific infertility” of phenomenology, but I would argue that phenomenologically informed cognitive science shows exactly the opposite, namely, the fertility of including phenomenology as a key component of cognitive science.

“Just out of curiosity, what would it take to make a neglect account of phenomenology plausible for you?”

By “phenomenology” here I take it you mean conscious experience itself. I’m not sure I understand what it would mean to explain the phenomenon of consciousness itself in terms of neglect. “Neglect” refers to biases in attention, and I don’t see how consciousness can be exhaustively explained in terms of attentional biases. If you mean that certain features of cognitive function that influence experience may turn out to crucially involve mechanisms of neglect, then again I’d say that’s something to investigate and decide in a case by case way.

“Or is this just the way it seems upon reflection? Is it simply a coincidence that our brains have no way of sourcing their own operations, and that transcendental posits act as sourceless (that is, nonempirical) sources of functional constraint? If there is a connection, it would certainly explain a number of very curious things about the ‘transcendental’ (and do so, once again, on the ontological cheap).”

I think we are working with different concepts of the “transcendental” here. Your understanding of it seems Kantian—something ahistorical, formal, a priori, and in these ways outside empirical experience. But the concept of the transcendental in Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger (though avoided the word), and contemporary phenomenologists such as Zahavi refers to that which makes possible the meaningfulness of experience (or the “relevance space” of cognition, to use a more cogsci idiom), and this includes antecedent historical and social structures, embodiment, and the workings of intentionality (e.g., how we experience time in virtue of certain synthetic cognitive functions). So understood, the transcendental isn’t “sourceless.” On the contrary, transcendental analyses are concerned precisely with (among other things) specifying the sources of the transcendental (embodiment, culture, etc.).

I think I have decisive responses to your concerns (for instance, I’m a former Heideggerean), but e-debates quickly become unwieldy when they fracture, and I’ve taken too much of your time already (for which I am sincerely appreciative). So let me leave you with a final salvo. Since I think it’s only a matter of time before our growing scientific understanding of metacognition filters into theoretical debates on these issues, and since I think it spells disaster for the neurophenomenological project as you conceive it, let me explain why:

“Phenomenology is not based exclusively on first-person metacognition; it’s also based on conceptual/theoretical analysis, intersubjective methods of eliciting careful descriptive reports about experience, and methods for refining first-person attention and awareness. All of these things taken together are precisely the kinds of methods that enable us to get beyond certain entrenched forms of metacognitive neglect”

misdiagnoses the challenges you will increasingly face as our scientific picture of reflection becomes more refined.

Metacognition is fractionate and specialized, exactly as we should have expected, given the high metabolic cost of getting things right. This means the information accessed via deliberative, phenomenological metacognition is *special purpose information.* If the information available for trained reflection on our phenomenology is skewed to the solution of practical problems (such as tongue-biting, improving task performance, and so on), then we should expect it to have a substantial impact on our phenomenological analyses. If deliberative metacognition can only dredge up the information required to cue tongue-biting, etc., then why should we think it provides the inferential basis for ontological claims regarding the fundamental nature of experience?

This is a pretty straightforward question, and like I mentioned, I’ve pestered a number of phenomenologists now, and all of them have punted.

The fact is, neurophenomenology presumes exactly what you assert: that, given the proper methodological and empirical constraints, the information and capacity available to deliberative metacognition provides a sufficient basis to make substantive phenomenological claims. All we know for sure, however, is that information and capacity provides a sufficient basis for solving a number of practical problems. And frankly, it’s hard to imagine why we should evolve anything so exorbitant as a capacity for fundamental self-insight. At the same time, neglect explains why it *seems* that we have this amazing ability: since we lack any meta-metacognitive systems, we have no way of intuiting the limits, let alone the structure, of metacognition. Thus we characterize it as undifferentiated and general, we make the same mistakes we generally make when we seek conclusions in conditions of information scarcity, the difference being, we have no way of cognizing that scarcity as such.

In a sense, I’m accusing neurophenomenology of not being *ecological.* If you look at the cognitive ecology of metacognition—the fact that it’s attempting to track the most sophisticated system we know of—then its radically heuristic nature becomes plain, as well as the kinds of limitations and confounds we should expect to plague its exaptative applications.

I think the burden clearly lies with neurophenomenology on this point: Given the picture of metacognition emerging out of cognitive neuroscience, why should we think we possess the metacognitive juice to confidently posit something so extraordinary as, just for example, alternate ontological orders of existence?

I have not carefully studied all of the above comments but I suspect that the described improvements in perception can be attributed simply to learning. Of course, learning involves neurophysiological concommitants.

I have written a book and articles which include the thinking that consciousness is discontinuous but that we are not aware of the interruptions.

Hi Scott,

This is a reply to your last comment, further up in the thread, since I can’t seem to reply directly to it there.

As I understand your position, your argument is (1) that “metacognition” is a name for a bunch of special purpose, heuristic capacities, which deliver, at best, information geared to practical problems of cognition and action; (2) the information that these capacities deliver does not directly tell us about our inner workings as cognitive systems; (3) therefore phenomenology cannot tell us anything informative about experience, either at a descriptive, empirical psychological level, or at a transcendental level concerned with conditions of possibility for experience (given that phenomenological analysis and reflection require metacognition).

I agree with (1), subject to two qualifications: (i) I ‘m not at all persuaded that metacognition fractionates into specialized, *modular *capacities, because I think the cognitive neuroscience evidence doesn’t favour modularity (indeed, counts against it); and (ii) I think it’s an open empirical question the extent to which mindfulness practices and related forms of phenomenological investigation may attenuate cognitive and metacognitive biases. I also agree with (2) if “inner workings” refers to our subpersonal cognitive architecture. However, I don’t think (3) follows. (Certainly, it doesn’t follow as a matter of logic.) The point of phenomenology is not to reveal our subpersonal cognitive workings, but to clarify analytically the character of experience as such; furthermore, such clarification provides important constraints on theories and models of the underlying cognitive system. Finally, I think you’re trying to decide the question of what phenomenology can and can’t do too much from the armchair based on a particular (and, to a certain degree, contentious) view and assessment of metacognition, whereas I think the question needs to be addressed empirically (in the manner neurophenomenology proposes), and that it remains at this point very much an open and fertile question.

“If deliberative metacognition can only dredge up the information required to cue tongue-biting, etc., then why should we think it provides the inferential basis for ontological claims regarding the fundamental nature of experience?”

I haven’t and don’t claim that phenomenological reflection gives us the inferential basis for making such ontological claims. The claims that (my kind of) phenomenology makes are ones about the describable, structural characteristics of experience and the a priori conditions for such characteristics (which have to do with embodiment, embeddedness, etc.), but not about whether we should be idealists, physicalists, panpsychists, etc, about consciousness. I have my own views on those questions, but I don’t take them to be decided purely by phenomenology.

“Given the picture of metacognition emerging out of cognitive neuroscience, why should we think we possess the metacognitive juice to confidently posit something so extraordinary as, just for example, alternate ontological orders of existence?”

I don’t take myself to be positing “alternate ontological orders of existence” (I’m also not sure exactly what that means). The transcendental in the phenomenological sense isn’t an alternate ontological order (e.g., in a dualist or idealist sense); it’s rather an alternate logical order from what is given empirically, in the sense that it’s that which functions as a condition of possibility for that which is the case empirically. For example, the world of culture and social relations is an antecdent condition of possiblity for having a certain sense of self; it’s thus transcendental with regard to the individual sense of self, but it’s not an alternate ontological order (e.g., an immaterial order in a Cartesian sense or a noumenal one in a Kantian sense).

I dunno, Evan. The challenge neurophenomenology faces strikes me as quite simple, despite your many qualifications (formal transcendentalisms just make metaphysics more spooky, if you ask me, attempts to spin a virtue out of information scarcity). It really comes to this: insofar as our ability to cognize *anything* turns on information availability and cognitive capacity, the discovery that metacognition consists of “a bunch of special purpose, heuristic capacities, which deliver, at best, information geared to practical problems of cognition and action” possesses immediate and obvious relevance to our ability to determine the “analytic character of experience as such.”

If we were Medievals confronted with a Chandra x-ray feed, our only way to understand what we were describing would be to understand the access and capacity possessed by Chandra. The point is that access to information regarding the mechanisms mediating the feed would almost certainly have a *dramatic* impact on their understanding of the feed. Short of knowledge of Chandra, we could expect our Medievals to raise a cloud of theoretical contexts about the feed, each making different sense of the same narrow band of data, all of them underdetermined. Perhaps the fact that we’ve been baffled by ourselves these millennia should come as no surprise, given that, until recently, we lacked the capacity to understand the how behind the what of the soul! We’ve just had the feed all this time.

Like our hypothetical Medievals, you have no way to say *in advance* that your interpretation of the feed gets Chandra right, that it possesses the access and capacity required (given other resources) to cognize the ‘analytic character’ of the feed.

In terms of modularity, you presume Chandra will look one way, and I presume it will look another. Science will sort it out (I actually think it has… but). Either way, your own account of the stream shows 1) how phenomenology, despite its rational precautions, is nonetheless vulnerable to neglect effects, and 2) how neurophenomenological explanations can *explain away* apparent characteristics of experience. Meanwhile, you agree that metacognition is heuristic, which means that you agree that metacognition derives computational efficiencies via neglect. This in turn suggests that neglect effects (like the ‘stream’) *could* be quite pervasive.

You suggest that neurophenomenology takes all these issues into consideration, but if so, where? Where in the literature does neurophenomenology tackle the problems raised by the neuroscience of metacognition, let alone spectre of metacognitive neglect? I’d love to check it out—almost as much as I would love to be argued out of all this. It’s an unnerving picture I’m peddling, to say the least.

Hi Evan –

Couple of questions. First, it seems that there is a distinction between discreteness and periodicity. Wave phenomena, for example, are periodic yet continuous, right? So I wonder how the experiments you describe establish that consciousness comes in discrete pulses rather than continuous waves, for example. Or perhaps they don’t? If so, what sorts of experiments would?

Second, do you have any thoughts about why the specific mindfulness techniques invented by Buddhists thousands of years ago would succeed in revealing to introspection the actual nature of how the human brain works? Did they just get lucky and stumble upon this amazing introspective methodology? What specifically about the discipline they preach and practice makes introspection suddenly so veridical? And why would a historically contingent culture without any understanding of the brain as such develop such an amazing “cerebroscopic” technique?

Finally, the primary aim Buddhist meditative techniques is soteriological, not neuropsychological. The goal is not an accurate picture of how the brain works but salvation from suffering. Can you say something about how the two are related? Is it just an accident that the Buddha’s techniques for bringing about salvation just happened to also reveal the actual nature of neural functioning, thousands of years before anyone even knew what neurons are?

Hi Tad,

I’ll respond to your questions one by one:

(1) The experiment by Varela et al. (1980) has been taken as providing evidence that visual perception is discrete. The reasoning is that discrete perception implies that two distinct events will be judged as either simultaneous or sequential depending not only on the objective time interval between them, but also on their temporal relationship to some internal neuronal process that is discrete, such as the “up” and “down” states of neuronal assemblies, as indicated by the positive and negative peaks of the alpha cycle. (Another issue here, however, is whether these surface electrode waveform peaks can be taken as indicating a discrete internal process.) As I say in the post, however, this experiment has been difficult to replicate. The other, more recent experiments I mention show that perception and attention are periodic and pulsing, but not necessarily discrete. The question of whether visual consciousness is discrete or continuous remains an open empirical question, though it’s generally accepted now that it’s periodic and pulsing (at least on the time scale of tens to hundreds of miliseconds). For further discussion of these issues see the 2003 TICS paper by Van Rullen and Koch, “Is Perception Discrete or Continuous?”, which I link to in the post.

(2) I wouldn’t say that the mindfulness practices invented or discovered by Buddhists reveal how the brain works. Only neuroscience can reveal how the brain works. What mindfulness techniques do is sensitive one to aspects of experience that are hard to appreciate in the absence of a calm mind, stable attention, and acute meta-awareness. How to relate those aspects of experience to the brain and what they reveal about how the brain works is not addressed in Buddhism. For that we need cognitive science. So, in my view, it’s not right to say that mindfulness practices provide any kind of “cerebroscope,” though one does see such (misguided, in my view) claims made by “Buddhist modernists,” especially ones who want to use science to defend the faith.

(3) I agree that the primary aim of Buddhist meditative techniques is as you say. Traditional Buddhists may not care much about the brain, but Buddhist modernists, both Western and Asian, want Buddhism to be in step with science, so for them relating the soteriological practices to an understanding of the brain is important. My own view is that we need cognitive science to understand how meditation practices function cognitively and affectively, and to understand how they’re related to embodied and embedded cognition more generally. Those practices in turn can suggest new insights for cognitive science. But, again, I wouldn’t say that Buddhist meditation techniques reveal the actual nature of neural functioning.

Finally, in the case of the Abhidharma, although I believe some of its insights are related to Buddhist meditation practices, they’re also based a lot on abstract philosophical analysis. So, in this respect, they’re more analogous to Kant or James than to neuroscience.

Hi Scott,

Thanks for the continuing conversation and debate.

I don’t find the Chandra analogy compelling, because metacognition isn’t an outside reading of a data feed; it’s a collection of processes that reshape the processes providing the data feed, especially as a result of training via mindfulness practices (or so I hypothesize).

Regarding neurophenomenology engaging the cognitive science of metacognition — this is done to some extent in the papers by Petitmengin (see also the ones co-authored with Bitbol) that I mentioned earlier. It’s also something that I discuss in Waking, Dreaming, Being, though there’s more work to be done. If you want to see my take on how the cognitive science of mindfulness relates to metacognition, there are some remarks in this recent short talk of mine — they don’t directly address your concerns but they might give you a sense of where my own thinking is heading these days: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OJHCae1liAI

Wonderful, thank you. I’ve been expecting your book to arrive ‘any day now’ for the entirety of our exchange.

“I don’t find the Chandra analogy compelling, because metacognition isn’t an outside reading of a data feed; it’s a collection of processes that reshape the processes providing the data feed, especially as a result of training via mindfulness practices (or so I hypothesize).”

I have the same problem with the analogy, but for me, it simply compounds the difficulty of what you’re attempting. Just think of the nightmare it represents in Bayesian terms. If one defines cognition minimally as involving systematic comportments, then ‘observer effects’ scuttle the whole show! To me, this underscores the artificiality of ‘experience’ at every level of theoretical description, as well as explains why we still, after all these years, so wildly disagree about our explananda.

Either way, I think it’s hard to disagree with the prudential upshot of my case. All I’m asking is that you kick over the rocks you’re describing, look underneath, ask yourself what kind of information is neglected, and how it might impact your analysis of ‘experiential character.’

Here’s a thumbnail neurophenomenological account a la neglect: Perhaps the now appears to ‘stand’ because metacognition has no way of sourcing temporal awareness, no way of tracking the activity of tracking. As should come as no surprise, we’re not built to accurately cognize our cognition of time. So when we reflect upon the passage of now, *it strikes us that nothing passes.* The ‘standing now,’ I think, is a clear cut example of what might be called a neglect identity effect. The phenomenological now, far from carving out some kind of transcendental space of ‘lived life,’ turns on a cognitive illusion, arising–just as visual illusions arise–from the application of some heuristic capacity out of school. Augustine’s original declaration was perhaps the most honest one!

Here’s a tough question: How could our cognition of our (experience of) temporal cognition *not* make this error?

As with the ‘stream,’ we intuit identity for the simple want of information regarding distinctions. The phenomenologist interprets these identities, and the neurophenomenologist takes them as neuroscientific explananda and sets about finding systematic correlations. Since the original error is systematic they are correlations to be found, and the neurophenomenologist is convinced they *have* to be onto something. (How does neurophenomenology typically handle hidden variable problems?)

Heuristic neglect has more explanatory juice than you might think. It certainly provides a parsimonious way to understand the paradoxicality of experience.

Evan,

Thank you for posting this fascinating article and engaging in the comments sections! It means so much to the readers!

I have two questions to you.

The first is directly related to what you wrote above:

Like a miniature version of the wake-sleep cycle, neural systems alternate from moment to moment between phases of optimal excitability, when they’re most “awake” and responsive to incoming stimuli, and phases of strong inhibition, when they’re “asleep” and least responsive. Moments of perception correspond to excitatory or “up” phases; moments of nonperception to inhibitory or “down” phases. A gap occurs between each “up” or “awake” moment of perception and the next one, so that what seems to be a continuous stream of consciousness may actually be composed of rhythmic pulses of awareness.

However the “up” activity pattern in the brain does not happen at the same time across the entire brain. The waves seem to run through the brain, originating in many locations. Am I correct? If so, how would you interpret these “up” phases and the conclusions derived from them in the light of brain waves being “non-global”?

The second one is related to the post, but not directly, I think.

In the literature we often read about “brain states” and “states of the mind”. What is your take on these concepts? Do you think that a [rhythmic] pulse of awareness corresponds to a state of mind?

Hi,

Yes, I agree that “up” and “down” states are not uniform across the entire brain. The idea is that there are shifting and distributed oscillatory patterns at both local and large-scale levels. So the states I’m talking about in the case of perception are ones involving mainly sensory, associative, and frontal cortices; at least, those are the ones being tracked by these kinds of EEG time-frequency analyses of perception.

I think the concept of a rhythmic pulse of awareness is a mental-state concept (“awareness” is a mental concept) and that in these experiments it’s being correlated with rhythmic oscillatory neural activity (a brain-state level concept). The correlation is happening via behavior — what the participant reports seeing/detecting vs not seeing/detecting. So, yes, they do correspond, but “correspond” here means “is correlated with.” The deeper question about the nature of that correspondence (is it an identity, realization relation, etc.) isn’t decided by just establishing the correlation.